Above: R.B. Kitaj. Eclipse of God (After the Uccello Panel Called Breaking Down the Jew's Door), 1997-2000. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35 15/16 in. x 47 15/16 in. Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Memorial and S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Funds, 2000-71. Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. Photo Credit: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY. © 2020 R.B. Kitaj Estate

Socialist Yiddish poet Avrom Lesin, who grew up in Minsk in the 1870s and 1880s, recalled that as a child he visited a local tavern whose owner he knew. There he saw “[Gentile] drunkards lay around on the dirty floor, embracing and jostling one another, singing with hoarse voices, snoring,” as the Jewish owner stood at the door and “laughed with such deep contempt that his whole body shook.” Writing about his experience in the New World, Yisroel Kopelov, a Russian-born radical, who arrived in America in 1882 and became active in the anarchist movement, remembered his days (late 1880s) as a traveling salesman in New York’s poor neighborhoods. As he walked through the city’s Irish sections, Kopelov was shocked by what he witnessed: “In the Irish neighborhoods the dirtiness was exceptional!” and “roused disgust when looking at them. Just the smell from the house was unbearable!”i

Many scholars have argued that American Jewish liberal/ progressive leanings are a direct result of the alleged universal values of Judaism, and/or Jewish historical experience. According to those interpretations, Jews often identified “down,” that is, with the downtrodden and other marginalized groups. Jewish historical experience, however, reflects a different streak altogether. Throughout most of their history, Jews had usually shown little interest in—and quite often utter contempt toward— the surrounding lower-class and lower-stratum non-Jews. In eastern Europe, the muzhik/poyer (peasant) usually embodied those low-class Gentiles. In Yiddish folklore, in numerous memoirs and autobiographies, and in the Jewish press, certain archetypal images of the peasantry were entrenched: the local peasantry (whether Belarusian, Polish, Romanian, Ukrainian, etc.) was usually portrayed as strong, coarse, drunk, illiterate, volatile, and sexually promiscuous. That imagery yielded songs like “oy, oy, oy/ shiker iz a goy / shiker iz er / trinken muz er / vayl er iz a goy” (drunk is a Gentile / drunk is he / drink must he / because he is a Gentile); sayings like “a Gentile remains a Gentile”; “when the Gentiles have a feast they beat up Jews”; “when the Jew is hungry he sings. When the Gentile is hungry he beats up his wife”; and “the Jew is small and Vasil (a common Ukrainian name) is big.” There were also contemptuous names for Gentiles, especially peasants, such as zhlob (a boor or yokel), dovar akher (literally “other thing,” figuratively meaning something impure like a pig or an abominable person), shkots, orl (a more contemptuous term than goy, referring to the uncircumcised), poperilo, kaporenik (figuratively someone who is worthless), or just “Ivan.” That approach could be found even among ideologues on the Left, who espoused working-class solidarity. Such attitudes continued to manifest themselves in America, where Jewish immigrants often cast structurally low-class groups, such as the Irish and African Americans, as the New World’s reincarnation of the Slavic peasants, with many of their perceived negative characteristics.

Russian peasant women, 1909. Photo by Sergeĭ Prokudin-Gorskiĭ. Prokudin-Gorskiĭ photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Contempt and fear of the non-Jewish lower classes had to do with the Jewish socioeconomic position as middlemen, who were also members of an ethnoreligious minority, and reliant on central authority for their ultimate safety. Therefore, the prevailing historical pattern was that Jews tended to identify “up” rather than “down.” More often than not, Jews aligned themselves with the central authorities who protected them from mob attacks, and many communities relied on Gentile rulers for their livelihood as well. Anxiety about non-Jewish masses was interwoven with disdain for their behavior

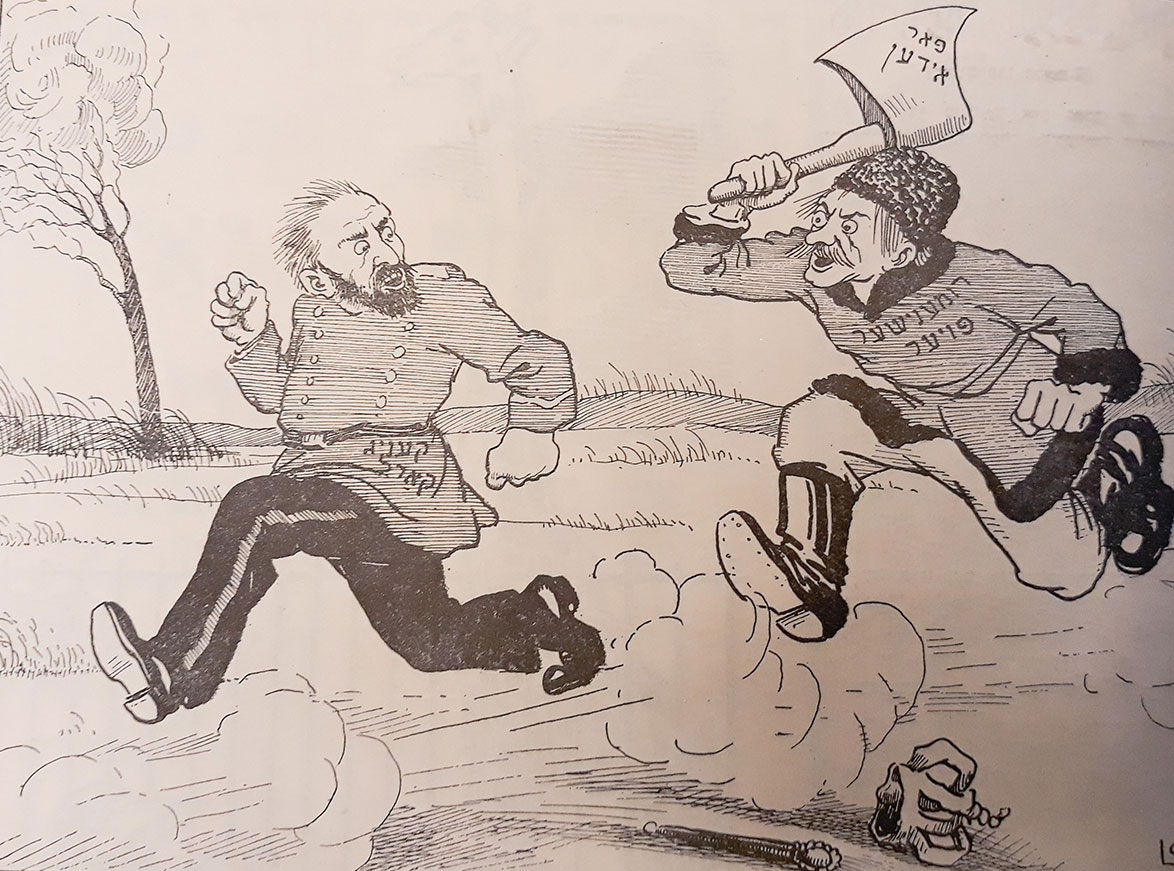

Cartoon from the satirical Yiddish weekly Der groyser kundes (1919) entitled, "Revolution in Romania." The caption reads, "King Karl: Hey, hey, we gave you the ax to hit Jews! Romanian Peasant: Hitting Jews won't help me, now I want to give it to YOU." Courtesy of the New York Public Library, Dorot Jewish Division.

Back in the 1960s, American Jewish essayist Milton Himmelfarb found similarities between the relations of contemporary American Jews to African Americans, and the relations of eastern European Jews to the peasantry. Himmelfarb asserted, “The Jews did not hate the muzhiks,” since Jews “are poor haters”; if anything, "Jews pitied the muzhik," while feeling "superior" to the peasants.ii Himmelfarb's characterization has much truth to it, since in many Yiddish sources, peasants seemed less threatening than the clergy or gentry, and there are many examples of sympathy for the peasants' plight because of their poverty and exploitation by the upper classes. Even hasidic sources, which usually emphasized what they saw as intrinsic differences between Jews and non-Jews, saw some redeeming qualities in the peasantry.

Countless accounts and folktales by eastern European Jews illustrated peasants as dim-witted people, whose ignorance could only compete with their ruthlessness.

Still, Himmelfarb's formulation downplays Jewish caution about revealing one's mindset in public. The non-Jewish majority’s hateful attitudes brought about systems of legal restrictions and various kinds of attacks that seriously impinged upon the lives of Jews; Jews’ political situation and historical experience as a minority therefore tempered the expression of their attitudes (that were hardly more elevated) toward the majority. Yet if overt Jewish hatred toward peasants was articulated less frequently, the Jewish approach toward them exhibited much scorn. Countless accounts and folktales by eastern European Jews illustrated peasants as dim-witted people, whose ignorance could only compete with their ruthlessness.

By the turn of the twentieth century, however, a vocal yearning for normalcy, to be ke-khol ha-goyim (like all other peoples) in economic and cultural life would become widespread, especially among Jewish nationalists and radicals. These Jewish modernizers looked at other nations and their peasant masses as “healthy,” down-to-earth, no-nonsense people, who rolled up their sleeves, toiled the land, knew how to defend themselves, and whose directness and simplicity were not corrupted in comparison with the alleged Jewish cowardice, casuistry, and nervousness. Moreover, the conduct of those nations became, to a large degree, a gauge of Jewish shortcomings. What is highly important in this context, nevertheless, is that the ideal of normalization did not change the traits attributed to low-class Gentiles, but rather their evaluation. For example, Zionist writer Yosef Hayim Brenner contrasted in 1914 “the millions of strong and patient” Russian peasants and their “formidable instincts” with the indecisive, hesitant Jews. That characterization did not prevent him from describing the Russian masses’ “slavish spirit” and “stupefying cruelty.”iii As before, the peasant was seen as simple, strong, and coarse, but by the early 1900s, such features became gradually more desirable by modernizing Jews.

GIL RIBAK is associate professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Arizona. He is the author of Gentile New York: The Images of Non-Jews among Jewish Immigrants (Rutgers University Press, 2012) and is currently working on a study of the representations of Black people in Yiddish culture.

i Avrom Lesin, Geklibene verk: zikhroynes un bilder (New York: Cyco, 1954), 24; Y. Kopelov, Amol in amerike (Warsaw: Brzoza, 1928), 157, 164.

ii Milton Himmelfarb, “Negroes, Jews, and Muzhiks,” Commentary (October 1966): 83–84.

iii Yosef Ḥayim Brenner, “Ha‘arakhat ‘aẓmenu be-sheloshet ha-krakhim,” Ben Yehuda Project.