Above: Detail from “Alpha Epsilon Phi.” 1950. Makio, courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives.

PEDAGOGY

Overview:

As American Jews found inroads into the country’s economic, political, and cultural systems, questions remained about Jews’ ability to reflect notions of American citizenship and white, Christian, middle-class standards for behavior and conduct. To help students understand the ways in which Jews often found greater access into 1940s–1960s American society alongside new challenges to overcome, an unusual, yet readily available resource is available to most teachers in college or secondary-school environments—the yearbook. I use the space below to outline how a guided activity of analyzing yearbook images of Jewish bodies—in this case, Jewish sorority women—helps to literally illustrate issues of gender and acculturation in modern America.

Context:

Founded in the first two decades of the twentieth century as American Jews began attending college in significant numbers, sororities provided young female Jews with several tangible and intangible benefits for those deemed “suitable” for membership. Offering housing, meals, and camaraderie, Jewish sororities afforded these women a chance to observe and absorb behaviors of their non-Jewish counterparts in the larger and more established white sorority system, which itself represented white Christian elites. Finding the doors of these non-Jewish clubs closed to them owing to social antisemitism, Jewish women across the country, particularly in the South and Midwest, sought out membership in Jewish sororities to enjoy experiences similar to those denied them in the Christian houses. Joining also facilitated these female collegians’ movements within what were seen as elite Jewish institutions, which primed their members for postcollege success through leadership training, social networking, and, often, marriage to men from the Jewish fraternity system.

.jpg?sfvrsn=a6dc9506_0)

“Delta Phi Epsilon.” 1957. Ibis, courtesy of the University of Miami Archives.

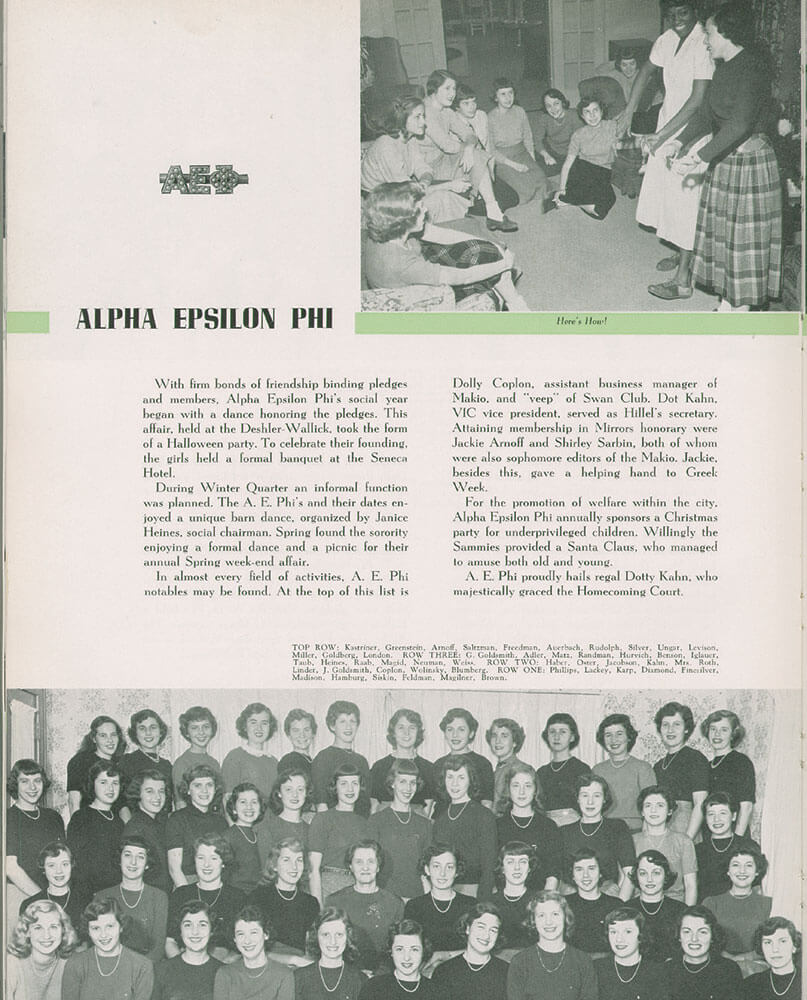

Jewish sorority women used their membership within the Greek system to promote their “good Americanism,” primarily through trying to demonstrate through their self-representation and philanthropic acts that they could embody the best of American youth culture and behaviors. Yearbooks were one of the most significant ways Jewish sorority women could showcase their members’ beauty and good taste to a broader non-Jewish audience. Since their entries appeared alongside those of the broader white Greek system in almost all college yearbooks across the country, they knew that their submissions to the publication would be an important place where viewers would observe, and possibly judge, the Jewish women’s looks and the extent to which they appeared equal to their Christian counterparts. With the reality of social exclusion present in their lives, the Jewish women were aware of their chance to visually make a strong first impression. While scholars and students often peruse sources to identify points of Jewish distinctiveness, historical yearbook photos of Jewish sorority women offer an instructive exercise on how “looking like everyone else” can in fact tell us important data about the aspirations and daily lives of a minority group.

“Alpha Epsilon Phi.” 1950. Makio, courtesy of The Ohio State University Archives.

Classroom Activity:

As a group or in small groups, students can analyze images like the ones here and consider the following:

• If you know nothing about sororities, what would you infer about these women based on what you see here? What specific elements of these images are you using to draw your conclusions?

• To what extent are these images focusing on the individual group members? The sorority as a whole? Why do you think that is?

• If you were to construct a stereotypical image of a woman from the 1950s, to what extent does what you see here conform to your imagining? How, if at all, does what you see here differ?

• How, explicitly and implicitly, do these images engage with ideas of beauty?

• What, if anything, is “Jewish” about these yearbook pages, in both text and image?

Takeaways to Consider:

• Jewish sorority women often aimed to present their members with no obvious “Jewish” context, both in imagery and text. For example, they might reference that various members went to, or held leadership positions within the Hillel Foundation, but would rarely use the word “Jewish” to describe their membership or activities. Looking at the members’ last names is often the easiest way to decipher whether the group was a Jewish one. Most sororities—even more than fraternities—did not have members of different religious backgrounds or ethnic communities in the same group until at least the late 1960s.

• Jewish sorority composite photos of each member often tried to appear uniform in approach, such as in the 1957 Peter Pan collars or 1950s pearl necklaces you see in the images included here. These were meant to highlight the members’ awareness of tasteful trends and/or their socioeconomic status through consumption.

• Whenever an individual sorority member gained recognition for her looks, such as Dotty Kahn from The Ohio State University’s Alpha Epsilon Phi chapter, the sorority would ensure her image and description would be featured prominently in its yearbook submission, a practice similar to non-Jewish groups.

• In both The Ohio State University’s 1950 submission and that from the 1957 University of Miami (Florida), the sororities detail their philanthropic endeavors, which were considered a foundational activity alongside the social aspects of Greek life. Note that the Alpha Epsilon Phi text discusses the group’s Christmas party for children and that “the Sammies,” a Jewish fraternity, provided a Santa Claus, with the assumption that these students were available to participate in the activity since they had no familial or religious obligations on that day.

Jewish sorority women used yearbook spaces to showcase Jewish standards of personal appearance and conduct as identical to those of non-Jewish houses.

Concluding Thoughts:

Jewish sorority women used yearbook spaces to showcase Jewish standards of personal appearance and conduct as identical to those of non-Jewish houses. Jewish practices and social relations, such as those between Jewish sororities and fraternities, were coded in that only those “inside” the system would understand the subtle distinctiveness found in these pages. These yearbook photos reflect issues of class, acculturation, and continued social antisemitism that Jewish women encountered in their daily lives and attempted to combat through strong social networks, communal engagement, and, of course, the attempted demonstration of Jewish compatibility in look and act with elite white Christian women’s norms of the period in question.

Further Reading:

Shira Kohn. “A Gentlewoman’s Agreement: Jewish Sororities in Postwar America, 1947–1964” PhD diss., New York University, 2013.

Shira Kohn. “Turning German Jews into Jewish Greeks: Philanthropy and Acculturation in the Jewish Greek System’s Student Refugee Programs, 1936–1940.” American Jewish History 102, no. 4 (October 2018): 511–36.

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz. Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures from the End of the Eighteenth Century to the Present. University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Pamela Riney-Kehrberg. “The High School Yearbook.” The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 10, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 159–67.

Marianne Sanua. Going Greek: Jewish College Fraternities in the United States, 1895–1945. Wayne State University Press, 2003.

SHIRA KOHN is a member of the Upper School History Department at The Dalton School. She, along with Hasia Diner and Rachel Kranson, co-edited A Jewish Feminine Mystique? Jewish Women in Postwar America (Rutgers University Press, 2010) and in 2018, had an article focusing on Jewish student refugees in the United States during the 1930s published in American Jewish History. She is currently working on a monograph about Jewish college sororities and their encounters with civil rights and Cold War anticommunist movements.