Above: R.B. Kitaj. Eclipse of God (After the Uccello Panel Called Breaking Down the Jew's Door), 1997-2000. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35 15/16 in. x 47 15/16 in. Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Memorial and S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Funds, 2000-71. Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. Photo Credit: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY. © 2020 R.B. Kitaj Estate

The three of us are Jewish teacher educators committed to equity-oriented teaching. Our shared concerns about how antisemitism is marginalized within the field of social justice teacher education, and our personal experiences with antisemitism in schooling, prompted us to come together to research how teacher educators with a stated commitment to teaching about diversity and equity for K–12 schools address hate, white supremacy, and antisemitism with teacher candidates.

Through interviews and collection of teaching documents from teacher educators across the United States, we have learned about beliefs and practices both discouraging and fascinating. Our findings offer empirical evidence of how antisemitism occupies a marginal place alongside the other “-isms” addressed within teacher education and also provide some insights into what factors shape teacher educators’ decisions to teach about antisemitism (or not) as part of their work related to diversity and equity.

Through this study, we learned that teacher educators engage preservice teachers in exploring how racism, classism, homophobia, and Islamophobia shape education. For example, a participant described a lesson in which preservice teachers were asked to analyze memes from the Internet around the Black Lives Matter Movement to begin discussions of systemic racism. Many of the participants illustrated examples using current events, including the mosque shooting in New Zealand, as a catalyst for dialogue around hate and modeled holding such discussions in K–12 classrooms. Strikingly, our participants report that they rarely, if ever, discuss antisemitism or antisemitic acts with their preservice teachers. If they do, they describe it briefly as part of larger discussions about religious discrimination and hate, particularly Islamophobia.

When probed about this stark contrast, many of the participants were halting in their replies, questioning themselves aloud about why they may not address antisemitism within their work as teacher educators. Notably, participants who identify as Jewish, or who mention having a Jewish partner, had similarly hesitant reactions, even as they acknowledged that they or their families might be directly affected by antisemitism.

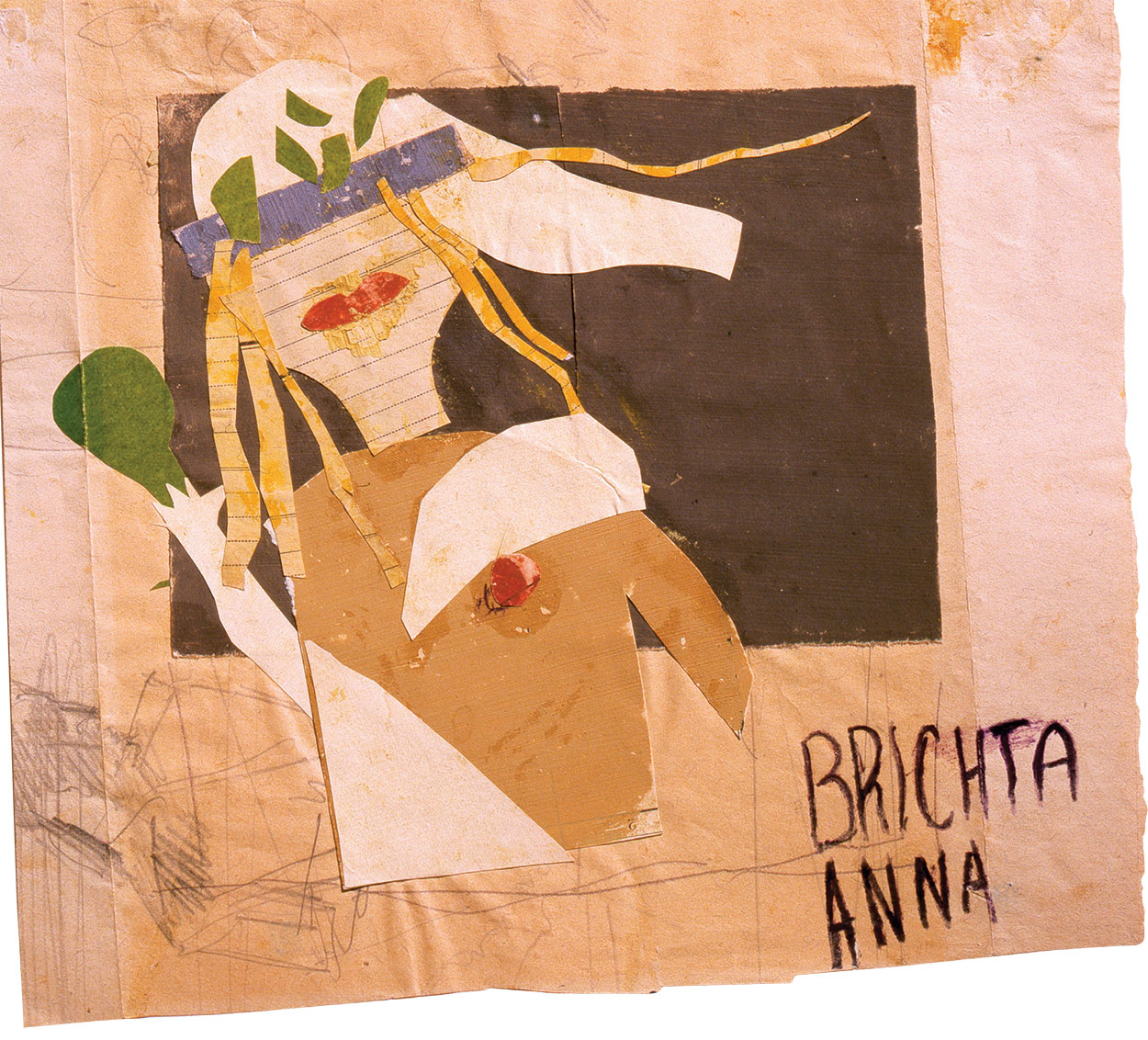

Brichta Anna. "Portrait of a Young Lady,” c. 1943–1944. Mixed media collage. 13.8 in. x 12.2 in. Artwork from children’s drawing classes in the Terezín concentration camp organized by the painter and teacher Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. Photo by Werner Forman Archive/State Jewish Museum, Prague/Heritage Images via Alamy Stock Photo.

Rationales for this omission vary but generally fit into two themes: not believing antisemitism is as serious a problem as other forms of discrimination, and a lack of resources for teaching about antisemitism. When arguing that antisemitism is not as problematic as other forms of discrimination, such as racism and Islamophobia, several participants state that most Jews are white or white-presenting and, therefore, benefit from white privilege in ways that make these discussions of antisemitism irrelevant or unimportant. This perspective was even shared by one of the Jewish-identifying participants who expressed shame around being white-presenting and, thus, getting some of the privileges that come with appearing white. This participant did not want to take airtime away from other problems that they see as bigger or more pervasive. Another non-Jewish participant even drew on antisemitic tropes, stating that Jewish people already use their privilege to draw unmerited attention to antisemitism, and arguing that Jews have “benefited from whiteness in a way that gets anti-Jewish discrimination more visibility.”

Several participants also describe a lack of resources related to teaching about antisemitism in the United States (as opposed to resources related to teaching about the Holocaust). For example, one participant talks at length about the availability of materials related to teaching about Black Lives Matter and other social movements but reports a struggle to find resources appropriate for helping teacher candidates understand antisemitism as a form of hate and white supremacy. Participants also describe how the hidden curriculum of their own doctoral programs, which were seemingly designed to illustrate educating teachers about diversity and equity, reinforced the idea that antisemitism is not necessary or important to address in teacher preparation. Their professors did not address antisemitism when teaching other “-isms” within courses on diversity and equity. One Jewish participant even reported that their attempt as a teaching assistant to incorporate a reading related to antisemitism into a multicultural education course was thwarted when the class ran short on time.

This research has created space for discussion around an issue that the three of us have felt deeply about for years, but have never felt able to articulate. We have all felt despair when our colleagues dismiss antisemitism as irrelevant to teaching for equity, or when antisemitic events such as the Tree of Life and Chabad of Poway shootings do not merit recognition as forms of white supremacy. It is our hope that, by drawing attention to the marginalization of antisemitism in teacher preparation focused on diversity and equity, we will encourage teacher educators to explicitly address antisemitism as a long-standing, systemic form of white supremacy rather than dismiss antisemitism as unimportant in the United States today. Further, although resources on teaching about American antisemitism in teacher preparation programs and K–12 schools are limited, organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League and Teaching Tolerance do offer some resources for teacher educators and teacher candidates who do not know how to start teaching about antisemitism. At the moment, though, bell hooks gives voice to our feelings of dismay and erasure when she writes, “[There is a] difference between education as the practice of freedom and education that merely strives to reinforce domination.”i The teacher educators we spoke to defined themselves as educators for equity, but we contend that if they continue to fail to include antisemitism in their discussions of hate and white supremacy with teacher candidates, then they are in fact reinforcing the white supremacy they believe they are repudiating.

JONI S. KOLMAN is assistant professor in the School of Education at California State University San Marcos. Her research focuses on equity-oriented teaching and learning, particularly for and in low-resource, highaccountability K-12 schools. She recently published the coauthored article “Cascading, Colliding, and Mediating: How Teacher Preparation and K-12 Education Contexts Influence Mentor Teachers' Work” in the Journal of Teacher Education.

JENNA KAMRASS MORVAY is a doctoral candidate in Curriculum and Teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University. Her research focuses on teacher activism. Her most recent collaborative publication is “Affective (An)Archive as Method” in Reconceptualizing Education Research Methodology.

LAURA VERNIKOFF is assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education at Touro College. Her work focuses on inclusive education, urban education, and teacher preparation. Her collaborative publication “Reimagining Social Justice-Oriented Teacher Preparation in Current Sociopolitical Contexts” is forthcoming in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education.

i bell hooks. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge, 1994): 4.