Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

Lovingly Escorting the Dead = Melavim Be-’Ahavah ‘et Ha-Metim

מלווים באהבה את המתים

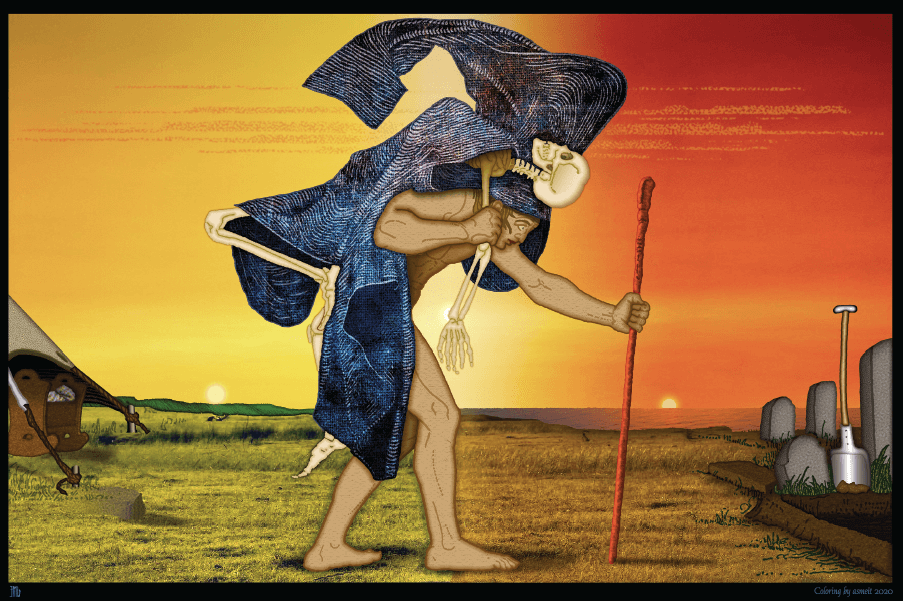

Andrew Meit. Lovingly Escorting the Dead (Melavim BeAhava et HaMetim), 2021. Digital painting.

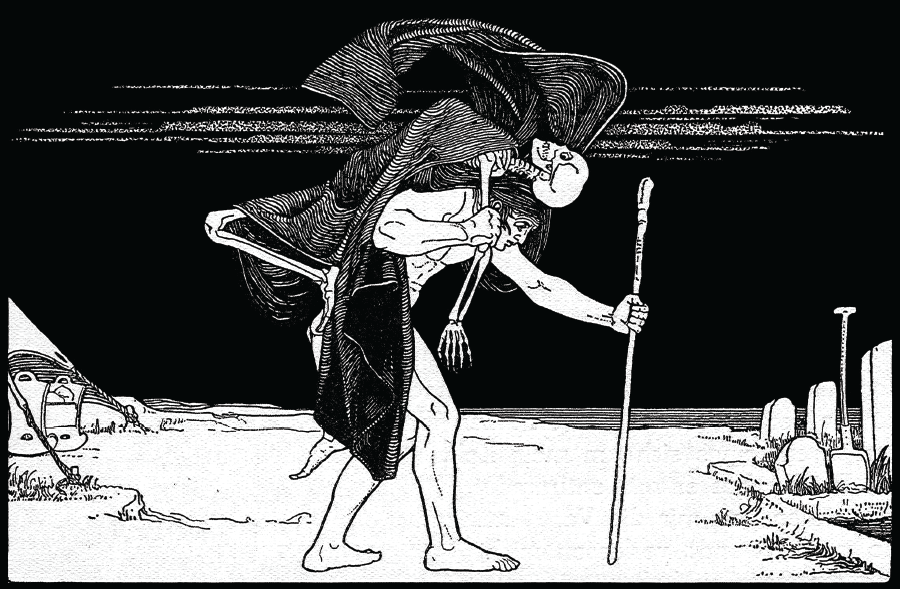

Illustration by Ephraim Moses Lilien published in Die Bücher der Bibel (Berlin: Benjamin Harz Verlag, 1923), via Wikimedia Commons.

Since childhood, creating art helped me deal with the daily stress of having several disabilities (deafblind from Rubella). Over time, art became part of my Jewish spirituality and an expression of my Judaism. I came to realize an image can be a prayer and a teaching. Later on, I discovered Ephraim Moses Lilien’s powerful Jewish black-and-white imagery. Currently, I create inspired interpretive colored versions of his images drawing upon decades of mastering Photoshop techniques. But who is Lilien? Lilien, an early twentieth-century German Jewish artist, created black-and-white ink drawings in the style of art nouveau exploring Zionist and Jewish themes and issues. Unique is his use of nude art elements and sexual suggestion.

This past year Lilien helped me soar over Covid. Covid is a deadly, overwhelming stressor for us all. I was determined to stay inside, remaining safe, but I needed something to keep me creatively focused. An art project lasting at least six months to a year would do.

I searched through Lilien’s work for an image offering a story about death. He explored death to make death personal, to help humankind see death. Finally, I found an unnamed image, which I named Life Cycle. Pouring my effort and vision into this Lilien image would bring me the stability I sought.

To be human is to die. This fact I learned very young. I learned also an eternal fact: we exist but for a whisper of time. Judaism teaches how to deal with those facts: caring for the dead, the dying, and the memories of them. In addition to sacred words, visual art can be another means to show how Judaism teaches compassion for the dead and dying. Lilien’s Life Cycle does that—thoroughly—which is why I choose the image to help me transcend Covid.

Getting the colors and blending transitions just right took a lot of experimenting. Nature often changes color when there is death, so the ground reflects that change.

Lilien’s Life Cycle presents a panoramic black-and-white image compressing all the human life-cycle stages: birth, life, and death. The extended life is presented as a man, representing humankind. Lilien does not give clues as to who the man, baby, or the bones are. Social relationships are, at best, implied. A vast, nearly empty black sky lies behind the man. However, Lilien provides a protective tent with a handmade, occupied crib and a used gravesite with a shovel ready to receive a body. It is not clear what ground the man is walking on: some rock, some grass, some desert, and a cliff!—all implying a rough life passage. There is a sea or lake just behind the graves and distant mountains behind the tent. The naked, stooped-over man carries on his back the heavy bones of the dead. He steadies himself using a tall walking staff, tightly gripped. He walks towards the graves with focused, wide, weary eyes. The skeleton faces upward with a leg pressed to the man’s back. The bones are wrapped in dark cloth—to respect the dead and to protect the living. Lilien places him—his journey—midway between cozy crib and empty grave plot.

It is challenging to translate Lilien’s images into color visually and semantically. My coloring is guided by his use of nature, natural settings, and symbolic objects. This includes an implied light source. I researched historical/ traditional colors before I colored the image. The stages of birth, life, and death give a natural arrangement of three parts that guides coloring. Naturally, the colors of sunrise, high noon, and sunset echo those same life stages. Getting the colors and blending transitions just right took a lot of experimenting. Nature often changes color when there is death, so the ground reflects that change. The baby’s quilt pattern uses bright hopeful primary colors; it is Jacob’s ladder, reaching to the divine. Although Lilien shows a black robe, considering the colors already used, I decided a dark blue robe with red flecks (symbolizing our blood) would be better. The walking staff is dark red, for by tradition’s blood, one’s life path is made steady—if held tightly. The Man(kind) is an earthling, so a darker brown skin befits him. To earth, he too will return one day.

Over the past year, learning daily of the mounting needless deaths, I steadily worked on coloring Life Cycle to compassionately carry the bones of those known and loved through my art with their memories. Holding onto the tradition of art and of Judaism steadied my art and my heart walking through a Covid valley of death.

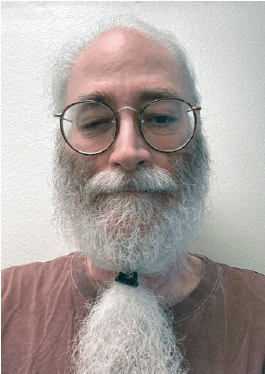

ANDREW MEIT is a self-taught artist with training from the Cleveland Art Institute and a BA in Religious Studies with minors in Math and Philosophy from Stetson University. He created the first digital version of the typeface used in Gutenberg’s Bible, “Good City Modern” and was lead software tester for the award-winning graphic-design software FreeHand 3/3.1.