Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

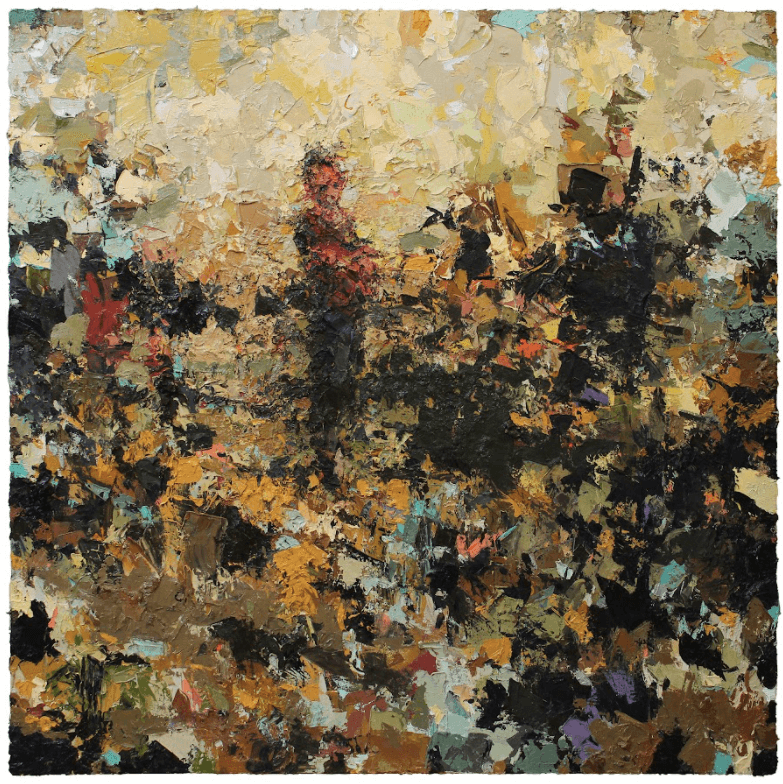

Joshua Meyer. Illimitably, 2019. Oil on canvas. 30 x 30 in.

My paintings are built up by layering thick paint. When you look at the overlapping marks, you can see time elapse. The paintings take months to complete, but leave their own processes open and visible. I work with live models over these spans. Illimitably shows not only a person at full-length, but the story of how he came into being. The layers recount the way the painting was made—the paint holds memories, accruing information, and allows the image to reveal itself incrementally.

... the paint holds memories, accruing information, and allows the image to reveal itself incrementally.

But I am curious about the accrual. I want to know how all of these selves interact and overlap. Each mark and each color is a point in time. By leaving my process open and visible, the paintings can contain—just as a person can—many overlapping stories. The art is not a fixed thing, it is a dialogue. Pthalo blue covers a cerulean blue, and an ochre hides a brighter hue as I try to resolve the image. The painting’s palette gradually turns autumnal. The heavy layers and colors move and build, adding up to a painting that should refuse to sit still.

My paintings are centered around people—family and close friends—who keep the art’s momentum rooted in relationships and personal stories. Illimitably is a self-portrait, however, with one foot planted squarely in reality, the painting veers off and begins to unravel. The paint takes on a life of its own, unmooring itself from its descriptive origins.

Art has an ability to hold multiple, competing truths. Judaism loves complexity too. Jews love to answer a question with a parable. Think about the hasidic tales, think about Kafka’s “Parable,” and, of course, think about midrash. Instead of walking away with a simple answer or solution, we learn to empathize with characters. We get to feel the struggle for understanding. We’re looking for those elusive openings so that we can burrow in and find meaning. We can enter and engage. Art has this power. Paintings are rich with contradictions, and as viewers we each have to do the work of weaving or sorting these aspects and impulses for ourselves.

Judaism can be legalistic as well, but the code is actually a book of arguments. The Talmud’s discussions and struggles are not a straight path at all. So Judaism teaches us that nothing is black and white. Everything is process and reevaluation. That is the way I approach the world, and it is the way I make art. I struggle and I seek. So it lays some philosophical groundwork for my art, and my art also lays some groundwork for my Judaism. When I exhibit my paintings in a gallery, the white walls rarely give away the fact that I am deeply enmeshed in the Jewish community. But art is omnivorous and more or less devours everything in my life, just as Judaism is really foundational to the way I think about the world.

.

JOSHUA MEYER is known for his thickly layered paintings of people, and for a searching, open-ended process. Meyer has been recognized with a 2021 CJP Arts and Culture Impact Award. The artist studied art at Yale University and the Bezalel Academy and has exhibited internationally, including solo exhibitions Tohu vaVohu at Hebrew College in Boston, Becoming at the Yale Slifka Center and NYU Bronfman Center, and the retrospective Seek My Face at UCLA’s Dortort Center. Meyer is represented by Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown and Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco. Website: www.joshuameyer.com