Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

I had been raised and educated to understand the history and events of the Holocaust. I had read Anne Frank’s diary, and had seen the terrifying images of bodies in black-and-white photographs. Those images were burned into my memory—cold and harsh historical documents of the destruction of groups of people connected to me through a common set of values in foreign places. I knew the images were created to provide records, to show the world what war and power was capable of doing if left unchecked, but the newspaper photographs were images belonging to my grandparents and parents. That made the pictures important as artifacts, but they were not my images, my story, or my connection to the Holocaust.

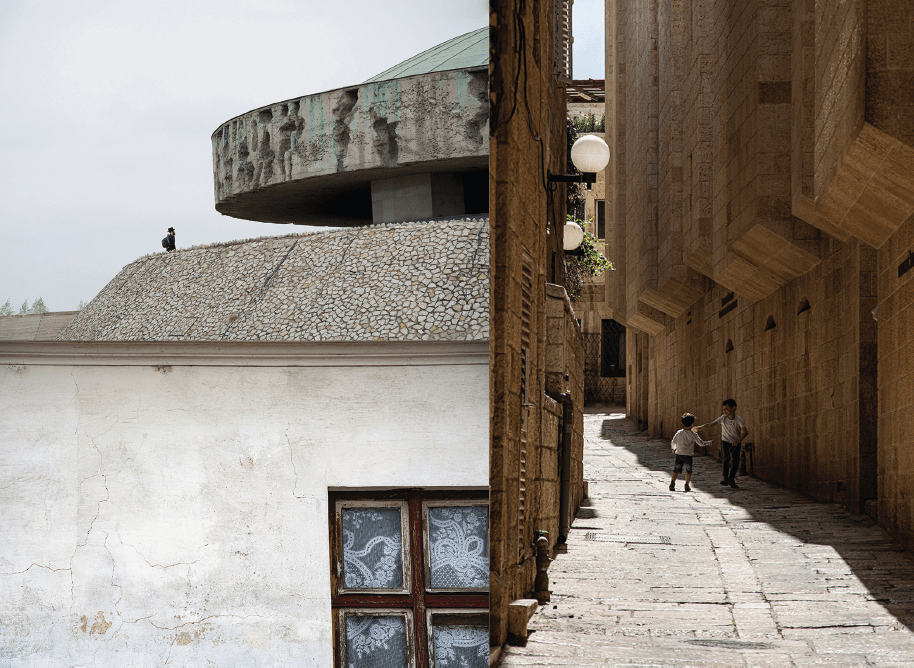

Marlene Robinowich. Majdanek Memorial, Lublin, Poland (top left), Window of Warsaw (bottom left) The Old City, Jerusalem (right). From the series Witnessing, 2019.

It was not until I saw rows of buildings and open fields for myself, standing next to my husband, friends, and community members that I realized I never understood how important my images could be in re-telling this larger story. I had been teaching photography for almost two decades. I took photos with my students, working on technical aspects, or of my children and places I lived and visited, and had always been interested in Jewish Studies and research in connection to making art. Then, after going on the International March of the Living trip in 2019 and agreeing to document the journey for the Savannah Jewish Federation, my work changed.

While the color palettes are similar, the contrast of death and life represents sadness and also joy.

Sorting through thousands of images over the past two years during the pandemic, I felt conflicted about being an artist who made work about the atrocities and still thought of the people in those news images as suspended in tragedy. By listening to those who lived through it, or to their children and grandchildren who know the stories by heart, and by seeing empty synagogues, crumbling buildings, and death camps that were not just remote, cold, dark crime scenes, I used my camera to process. What I recorded was not the images seen in movies; instead, they were beautiful bright green fields under cloudless blue skies surrounded by cities just out of view. This made me realize that if I wanted to use my images to understand, teach, and to relate to my peers and younger generations, the images would need to be different from those used to teach me about the Holocaust. My documentary photographs needed to be in color, to show the present, the surroundings, the connection between death camps in Poland and life in Israel.

The naturally muted colors of the stones and worn building facade reminded me about how life can change in almost insignificant ways that lead to destruction...

To create small narratives, I placed an image of a lace curtain bleached by the sun beneath an image of an Orthodox man standing alone in front of the enormous mound of ashes at Majdanek, where the creator of the monument, Wiktor Tołkin, engraved the message: “Let our fate be a warning to you,” next to an image of two young boys playing in the sunlit alley of the Old City in Jerusalem. While the color palettes are similar, the contrast of death and life represents sadness and also joy. The naturally muted colors of the stones and worn building facade reminded me about how life can change in almost insignificant ways that lead to destruction, and then can almost be erased if we forget to look for them. Each photograph uses asymmetry to emphasize balance, but not equality of the subject. It was important to include both the landscape and isolated people interacting with the space as a link to memory and to add a sense of movement to the stillness of the cold, hard structures with diagonal lines of sight taking the viewer out of the frame. Rough textures paired with vulnerable moments were created by leaving a smooth negative space surrounding each subject. The juxtaposition of these three moments is a reflection of the variety of emotions experienced in photographing, processing, and producing these images, and it is these images that helped me understand destruction and death, but also reminded me about survival and life through the use of photography.

Marlene Robinowich is a photographer, professor, wife, and mother who grew up in the Catskills, just north of New York City. She teaches at Savannah State University, the oldest public HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in the state of Georgia.