Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

“Engrave them, carve them, weigh them, permute them, and transform them, and with them depict the soul of all that was formed and all that will be formed in the future.” —Sefer Yeẓirah

Sefer Yeẓirah (the book of formation) is an early magical and cosmogonic text lovingly embraced by later kabbalists. It describes the forming of the letters of the alphabet as the elements of Creation, the “building blocks” of the cosmos. The very physical nature of this process is striking. It speaks to me of art making, of familiar studio practice, particularly drawing (“weigh,” “permute,” and “transform”) and sculpture (“engrave” and “carve”).

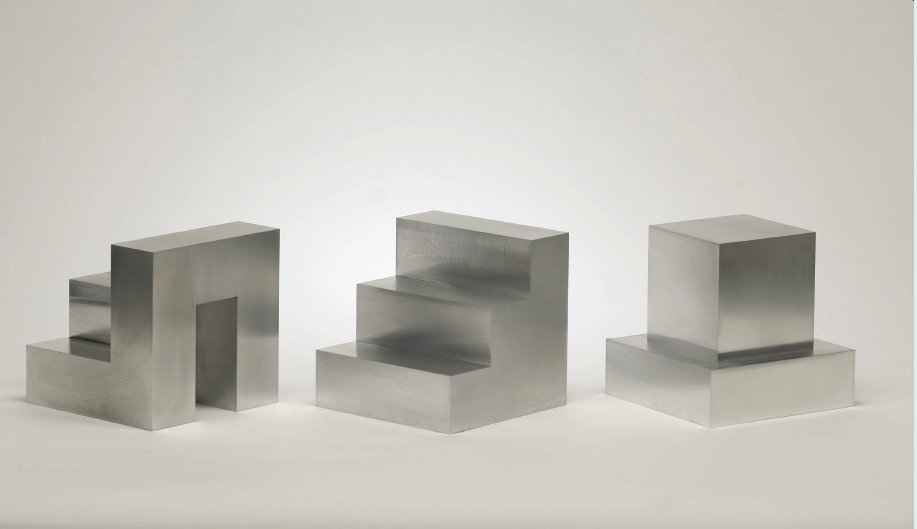

Robert Kirschbaum. Devarim Series, #41, #29, #23, 2013–16. Machined aluminum. 6 x 6 x 6 in. each.

This series of sculpture has its origins in my group of drawings, Devarim, which in Hebrew means both “words” and “things.” The plural of davar, devarim carries with it much of the same meaning as the Greek stoicheia, which can mean “elements” and “letters.” Devarim is also the Hebrew designation of the book of Deuteronomy. In Jewish mystical tradition, the universe is, in a sense, both written and constructed. It is a concept similar to logos in Greek and vac in Sanskrit: Creation emanates from a sound / a word. In the Devarim drawings, I begin with a nine-square grid, commonly used as a demarcation of sacred space, found most prominently in Judaism as the basis for Ezekiel’s Temple Vision. I draw a cube, each face divided into the aforementioned nine-square grid. Following the grid pattern, I then begin to carve out, weigh, transform, permute, and depict forms initially intended to function as plans for discrete objects that are fragments of a more perfect whole. In creating some of these images, I deliberately evoke Jewish symbols: Hebrew letter forms, Jewish ritual objects, and references to the Temple and Temple implements, as well as numeric symbols invoked by the introduction of plane shapes—hexagons, octagons, and circles.

The sheen of the metal makes these works seem almost transparent: they have weight and yet appear almost weightless—they have presence, and yet often disappear into their surroundings.

For my Devarim sculptures, I have, in keeping with the Sefer Yeẓirah, “engraved” and “carved” these forms from solid blocks of aluminum. Extending the metaphor of word and thing, letter and element, each piece can be considered a fragment of Creation. They express concretely the concept, from the Lurianic Kabbalah, of tikkun ‘olam, the repair or restoration of the world through the ingathering and reassembly of fragments of the universe shattered in the Creation, achieved through both concrete action and spiritual edification. The sheen of the metal makes these works seem almost transparent: they have weight and yet appear almost weightless—they have presence, and yet often disappear into their surroundings. I have carved forty-two of these works, to make reference to the one of the “secret” names of God, the forty-two-letter Name, and to create the elements for a larger work of installation art. Associated with the creation, the Zohar (the book of splendor) speaks of “the first forty-two letters of the Holy Name, by which heaven and earth were created.” The forty-two-letter Name is also said to consist of the first forty-two letters of the Hebrew Bible, and thought to have been engraved by God, during the Creation, on the stone that was used to separate the waters. That stone ultimately became the foundation stone of the Temple, and is regarded as the center of the universe.

ROBERT KIRSCHBAUM has exhibited and lectured about his work throughout the United States, India, and Israel, with some of his work currently being exhibited at ANU – The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv. Kirschbaum divides his time between New York City and Hartford, Connecticut, where he is professor of Fine Arts at Trinity College.