Above: Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in front of the former Ku Klux Klan Klavern No. 101 Auditorium

Douglas Rosenberg

Tzedek, tzedek tirdof:

“Justice, justice, shall you pursue”

― From parashat Shoftim

I was at a Black Lives Matter march in Madison, Wisconsin. My son was painting a mural on a street-level building which, along with others, had been covered in plywood in anticipation of what was to come. However, as the crowds surged and the marchers moved past me on their way to the capitol, I saw my rabbi surrounded by pandenominational clergy directly in the center of the group. For some reason, the sight of Rabbi Biatch standing up so publicly for justice within the context of all that had happened in the days preceding, and in the larger context of the political moment we were experiencing, brought on an unexpected wave of emotion. I found myself gesturing to him so as to say, thank you for representing us, the Jews who believe in justice for ALL people, especially for those people who are not Jews. We are citizens, humanists, and allies who, in applying the laws that guide us to the wider world beyond our own institutions and communities, perform mitzvot and instantiate the very things we affirm for the benefit of many causes outside of those that only affect us as Jews. For artists, especially Jewish artists from the twentieth century forward, this has been something of a clandestine practice that only in recent years has become legible as the art of social justice, or art as social practice.

I recently had a conversation with Ori Soltes, Georgetown professor of Theology and Art History, about tikkun ʿolam and the idea of a particularly Jewish social practice in the arts. Soltes noted that as far back as the late 1800s, the French Jewish From the Art Editorpainter Camille Pissaro stated that artists had an obligation “to use the knowledge that they gained to benefit the world at large: that art has a social and not only an aesthetic purpose.” He went on to say that “Pissarro’s idea of art as an instrument of secular tikkun ʿolam was taken to a particularly intense level two generations and an ocean away by the American sociopolitical realist painter, Ben Shahn.” Moreover, he remarked, “Shahn and a growing array of Jewish artists—particularly in America and with ever-increasing passion in the decades after the Holocaust—began to ask the question of where they fit in as artists, in Western art.”

As we move into the current era, the trend that Soltes observed is deeply rooted in the work of the artists included in these pages. For this issue about JUSTICE, I am thinking broadly about the ways in which contemporary Jewish artists look to social justice as a means of repair and regeneration. This is most certainly a contemporary method or modality for blending art, politics, and faith that seems in direct contradiction to what the (largely) Jewish modernist critics seemed to put in motion, at mid-century: a winnowing away of the personal to achieve the formal. Here, in the postmodern era, we find that, once again, the personal is political.

In a moment in which we are experiencing a generational shift among Jewish-identifying artists to a more inclusive and polyvocal, fluid understanding of Jewish identity, the politics and visual culture of Jewishness are foregrounded in astounding new ways. From graphic novels to digital art and highly charged dance and performance, to theater, music, and literature, we see both a return to ritual and a search for new narratives of the contemporary Jewish experience. Thus, the field is expanded even while acknowledging its own histories.

Vanessa Hidary, a New York poet who was featured on HBO’s Def Poetry Jam and who performs under the stage name The Hebrew Mamita, has a signature poem in which she addresses an experience that includes a sort of insult-as-compliment. She describes an experience with a stranger who, upon meeting her, noted, “Funny, you don’t look Jewish.” I think about that poem often, and especially in the context of creative work made from the experience of Jewishness, that does not always read as “Jewish” or by artists who “don’t look Jewish.”

In this moment of change, how do we speak about and acknowledge work by Jewish artists that strays from what we can readily or comfortably identify as “Jewish” subject matter? As artists and scholars seek to stretch the formal constructions of Jewishness and its relationship to the arts writ large, we can observe the gestalt of Jewish experience being recast in ways that may seem on the surface to be unlike any historical models. We see the metaphors of Jewishness being applied to performative or materially ephemeral gestures of faith or identity in ways that may be discomfiting or require deep conversation to fully embody the author’s intentions. We can see the tools of art making deployed to create an embodied experience of Jewishness in this moment in history, in ways that we have only seen hints of since the earliest days of modernism; in other words, art that does not “look Jewish” in the traditional sense. How do we communicate that which is ineffable, that which is at the core of our being, yet that which may have no form or materiality that resonates in the visual world usually associated with “Jewish”? How do we make, circulate, and analyze art practice across all media, made with a distinct acknowledgment of Jewishness in all its permutations, that speaks to the nuances of Jewishness in contemporary life? How do we simultaneously support and critique work that is intentionally Jewish, but does not, again, “look Jewish” ... work that questions and deconstructs the histories of Jewishness that may not welcome all of us or that no longer feels inclusive or righteous, and do so with respect to all forms and levels of observance that may not conform to our own ways of practicing or observing?

In this issue of Perspectives, the Justice Issue, I want to consider how we make space for work that both restates ancient ideas about Jewishness, but also work that seeks to repair the world, to deploy the tools that Jewishness gives us to be social justice workers, to perform mitzvot in the materiality of the arts and to hold space for all that we may not understand in the generational shift toward new models of self-expression, models that do not “look Jewish” or as Vanessa Hidary goes on to say, “do not sound Jewish.” Jewishness, seen through the frame of contemporary art, dance, theater, literature, and more, is a rich and diverse space. It is a space that asks us to consider who we represent and who we do not and with whom we seek to create community. It asks us to expand our understandings of what art may look like, what it might do in the world and who may do it in the name of Jewishness, in a fluid space in which issues of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, politics, history, and nationality are transposed into a new visual culture that is often both performative and conceptually thick with meaning.

Perhaps for the mid-century art critics Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, Meyer Shapiro (for instance), and others, justice was a feature of assimilation; the ability to blend in, to assimilate to the dominant American culture of modernism. However social justice confers its labors to the group outside oneself and perhaps even outside one’s own communities. Social justice requires the individual pursuing it to name themselves first, to commit to their own trauma, history of oppression, or other signifying event so as to be able to speak to individuals for whom such life experience is also the norm rather than the exception. for Jewish artists at this moment in history, undertaking social justice as a set of formal constraints for art making puts them squarely within the dialogue and the prescriptions of the most sacred Jewish texts. The writer and scholar Ori Soltes and others have identified tikkun ʿolam as a way in which contemporary Jews / Jewish artists can apply the lived experience of their own Jewishness toward solving greater cultural challenges. However, there are multiple ways to practice tikkun ʿolam; there is a clandestine version which is done under the radar so to speak, without outing oneself or one’s political ideologies, and another in which social practice is foregrounded and named, a process in which artists, Jewish artists, leverage the expectations of what it is to be Jewish in the most biblical sense to accomplish bringing healing or personhood or humanity to groups of people for whom such things have been denied or deferred. As such, the visual culture of Jewishness and Jewish identity in the twenty-first century is in flux, extending the representations of Jewishness in all its forms, beyond the dominant Ashkenormative visual language that often omits or erases the experience of Jews who live outside of that experience. The work featured in the Justice Issue is not a picture of justice or about justice, but rather enacts justice, extending the wisdom of Jewish texts into practice. It is work that inscribes the act of being just and the practice of striving for justice outside of one’s own personal sphere into the world at large. It is work by artists who may not “look Jewish” or who make work that does not “look Jewish,” but who strive to create works of art within a social justice practice that speak to the texts that most closely align with their own politics and with the real-life events that in some cases keep them from the fullness of participation in Jewish life or that celebrate life in just and humane ways for broader populations. As in parashat Shoftim’s Tzedek, tzedek tirdof —”Justice, justice, shall you pursue,” the work in this issue is actively in service of justice as restorative, and as a means of repair.

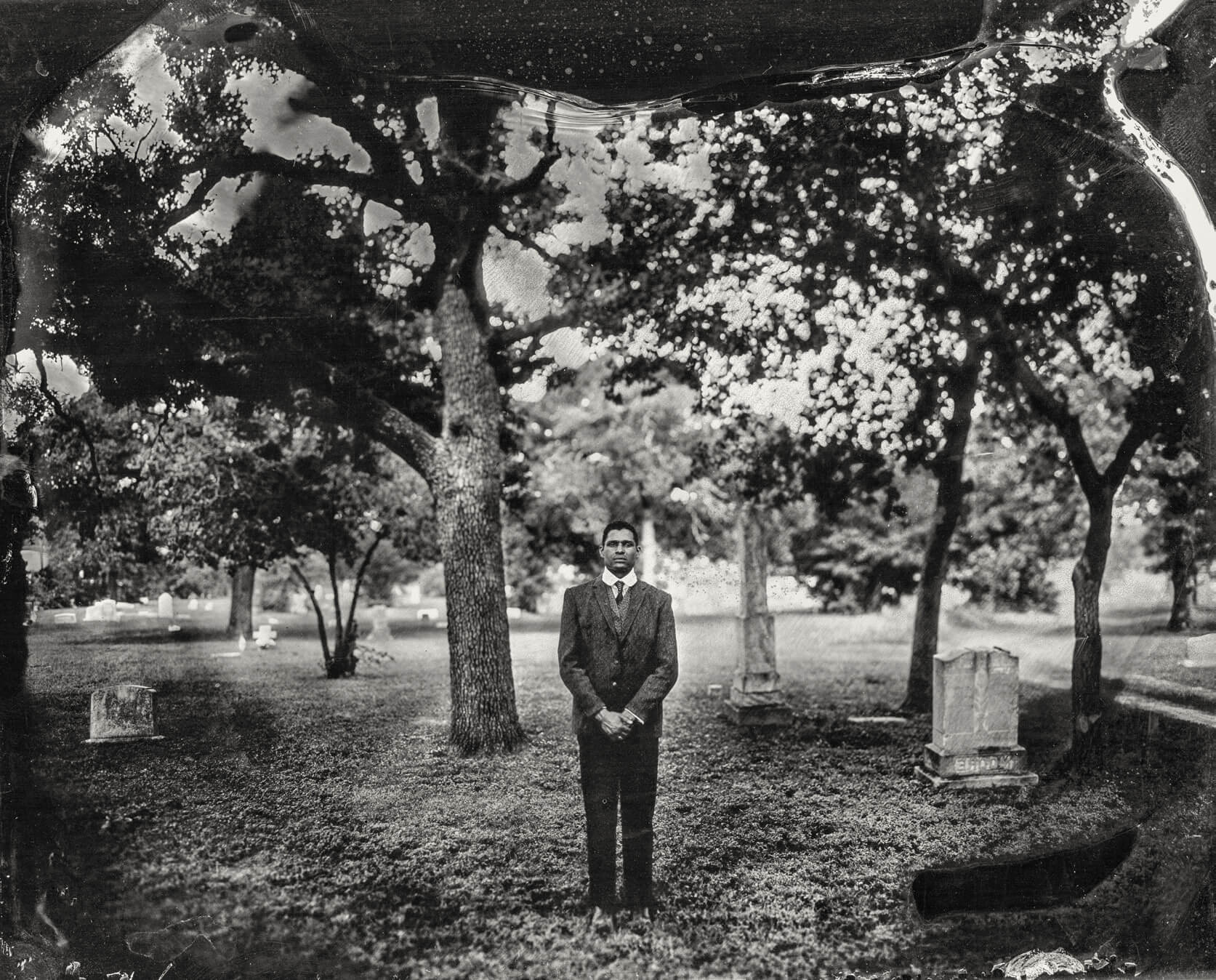

ADAM MCKINNEY is a choreographer, a dancer, and a visual artist who describes himself thusly:

I am a QueerBlackNativeJew. I was born into and am a product of the American Civil Rights movement. My parents (one of African, Native American, and Northern European heritages and the other of Eastern European heritages, both of whom are Jewish) were married in July 1965—two years before Loving v. Virginia when the Supreme Court of the United States struck down state laws banning interracial marriage, thirteen months after the signing of the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin, and exactly one week before racial discrimination in voting was outlawed with the signing of the Voting Rights Act.

He attended Orthodox Jewish Day school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and lives and teaches in Fort Worth, Texas, where he researches the city’s history of racism and instances of racial terror and violence. It is through this lens that McKinney began his Fred Rouse Memorial Project with the photographer Will Wilson. The project honors the legacy of Rouse, a butcher in Fort Worth, Texas, who was lynched in 1921. Through choreography and the historical form of tintype photography, McKinney inserts his own image into historical sites in Fort Worth “to remember Mr. Rouse by transporting my body across space and time, linking the anti-Black racial terror violence enacted upon Mr. Rouse to all the ways my own body has been, and is, targeted by racism.” This strategy of empathetic embodiment (which is shared among the artists in this issue) amplifies the very idea of the pursuit of justice found in parashat Shoftim; it deploys the tools that Jewishness gives us to do the work we are asked to do, to repair the world and to seek justice and renewal.

Artists such as McKinney live within a liminal space between multiple identities, all coexisting simultaneously; they are constantly the other, perennial outsiders in some community to which they belong. For many artists, intersectional, hyphenated, mixed race, or otherwise at the margins of one or more identities, justice is a very real, almost daily struggle. Justice in one aspect of such individuals’ sense of self may at the same time be in competition with justice in another identity group of which they are a member. Personhood, then, is in constant flux, and in the work of such artists we often see these frictions manifest as a kind of protest.

Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in New Trinity Cemetery where Mr. Fred Rouse was buried on December 12, 1921.

Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse at the site of the racial terror lynching where Mr. Fred Rouse was lynched on December 11, 1921, at 11:20 pm.

Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in front of the former City & County Hospital from where Mr. Fred Rouse was abducted on December 11, 1921, at 11:00 pm.

Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in the Fort Worth Stockyards where Mr. Rouse was first attacked on December 6, 1921, at 4:30 pm.

Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in front of the former City & County Hospital from where Mr. Fred Rouse was abducted on December 11, 1921, at 11:00 pm.

Photo by Amy Peterson

ADAM W. MCKINNEY is a dancer, choreographer, activist, and installation artist. He is a former dancer with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Béjart Ballet Lausanne, Alonzo King LINES Ballet, Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet, and Milwaukee Ballet Company. His work sits at the intersection of dance and performance studies, trauma studies, community, healing, and technology. His recent work, Fort Worth Lynching Tour: Honoring the Memory of Mr. Fred Rouse, a community-based augmented reality bike and car tour, was lauded by Mid-America Arts Alliance with an Interchange grant award. McKinney is Co-Artistic Director of DNAWORKS, an arts and service organization committed to healing through the arts and dialogue. He co-convened the 1012 Leadership Coalition to acquire and transform Fort Worth’s former KKK auditorium into The Fred Rouse Center for Arts and Community Healing. McKinney is associate professor of Dance at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth.

In the work of both LAURENCE MYERS REESE and Jessica Valoris, we see a recurring theme of the Sukkah, reimagined as contemporary spaces of recovery and refuge. For younger Jewish and/or queer artists the Sukkah is a kind of talisman or imaginary for the embodiment of a spiritual home. Art historian Lucy Lippard writes of “the lure of the local,” that place that accepts us and calls us back to where we feel most ourselves, a home and a healing space. Reese, whose work “examines Jewish paradigms of gender through a transgender lens,” set out to build a Sukkah made from handmade, discarded shipping pallets while reading from Isaiah 58, “a psalm that decries those who fast without making proper changes and repentance.” He notes that “that real return (Teshuvah) happens when we have fed the hungry and clothed the naked.” The site where Reese created this Sukkah was in Las Vegas, where temperatures reach 110+ degrees at times. Yet, the policy at the university where he was doing his MFA instructed those on campus to call the police anytime they encountered a “suspicious” individual. Reese notes that “in a climate (and economy) so inhospitable, we have criminalized poverty and disability, and further put our neighbors in danger. We cannot claim to be acting in righteousness (by making art, or doing research) without working for major systemic change.”

Photos from Laurence Myers Reese. The Dwelling I Desire, 2021/5782. Performance with amulet shoes, hand-built pine pallets, palm leaves, Sukkah.

LAURENCE MYERS REESE (he/they) works in performance, installation, painting, and video. He lives on occupied Southern Paiute lands, in Paradise, Nevada. He received his MFA from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) in 2022 and his BFA from the University of Oklahoma, Norman in 2012. He is the cofounder of the Vegas Institute for Contemporary Engagement, a research lab for art and experimentation and assistant to the chair at the Department of Interdisciplinary, Gender, and Ethnic Studies at UNLV. Reese’s writings are found in Art Focus Oklahoma, Southwest Contemporary, and Settlers + Nomads.

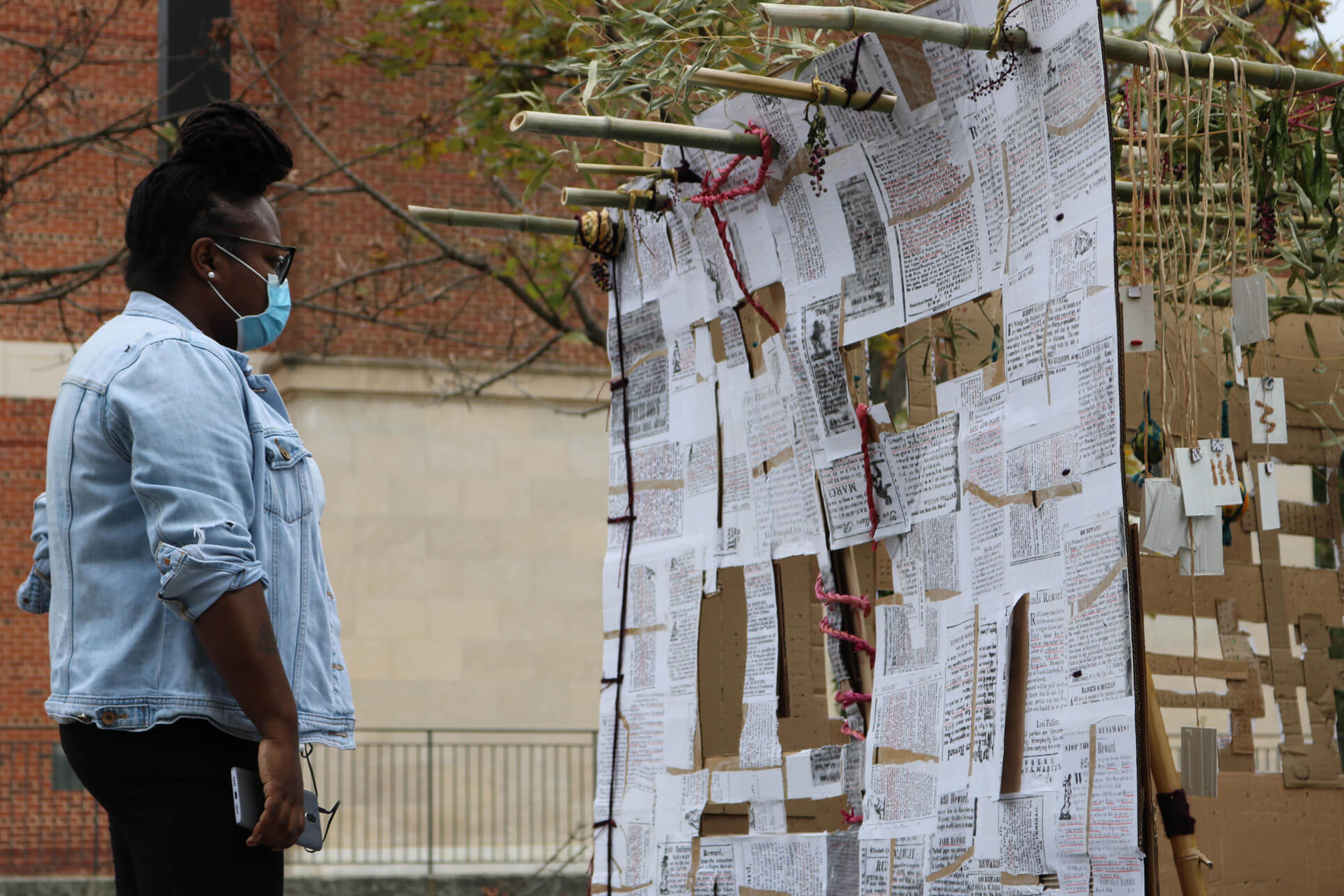

JESSICA VALORIS frames The Black Fugitive Sukkah as “inspired by the Judaic tradition of sukkah-building and the African American tradition of the hush harbor, traditionally a place where enslaved people would gather in secret to practice religious traditions. She says, The Black Fugitive Sukkah “is a temporary tabernacle, that creates space for deep listening and reflecting on the lessons that emerge from honoring legacies of Black fugitivity.” For Valoris, such community-based projects and collective care are rooted in the sacred traditions of both her Black and Jewish ancestors.

Jessica Valoris sets up the sukkah to honor self-liberating ancestors and histories of Black fugitivity. Photo by Imogen Blue

Community member Juanita Bazemore reading runaway slave ads that cover the sukkah.

Stones placed at each corner of the sukkah honoring self-liberating ancestors.

JESSICA VALORIS is a Washington, DC–based artist and community facilitator. Weaving together mixed media painting, sound collage, and ritual performance, Jessica creates sacred spaces that activate ancestral wisdom, personal reflection, and community care. Inspired by the earth-based traditions of her Black American and Jewish ancestry, Jessica explores ideas through the lens of metaphysics, spirituality, and Afrofuturism. Using art as a catalyst for collective healing, Valoris affirms the joy and vitality of Black people, complicating flattened histories of oppression, and creating space for affirmative celebration and redefinition. Jessica values collaboration with community-based cultural workers and collectives, and her work supports culturally relevant wellness and resilience.

Neither Jews nor Jewishness are monolithic and representation matters; inclusion is a particular kind of justice. Lack of representation and inclusion in matters of faith or belief could most certainly be considered a kind of injustice. I am writing from Madison, Wisconsin, in the United States of America, and here in the United States we have a tendency to portray Jewishness in a very narrow bandwidth of experience. Ashkenormative representations of Jewish life and Jewish culture are ubiquitous and that extends into the arts historically as well. However, within the generational shift and conversations about Jewish identity we begin to see Jewishness performed as a part of the fabric of a larger, more inclusive social justice movement. We are gay and straight, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, out married, Jewish by birth or by choice, secular or observant, Ashkenazic, Sephardic, Mizrahi, but still we pursue justice either individually or collectively. Many contemporary Jewish artists reflect that spirit of intersectionality in their art as a means of celebration or as a corrective that may extend a certain degree of participatory rights to individuals at the margins of Jewish community.

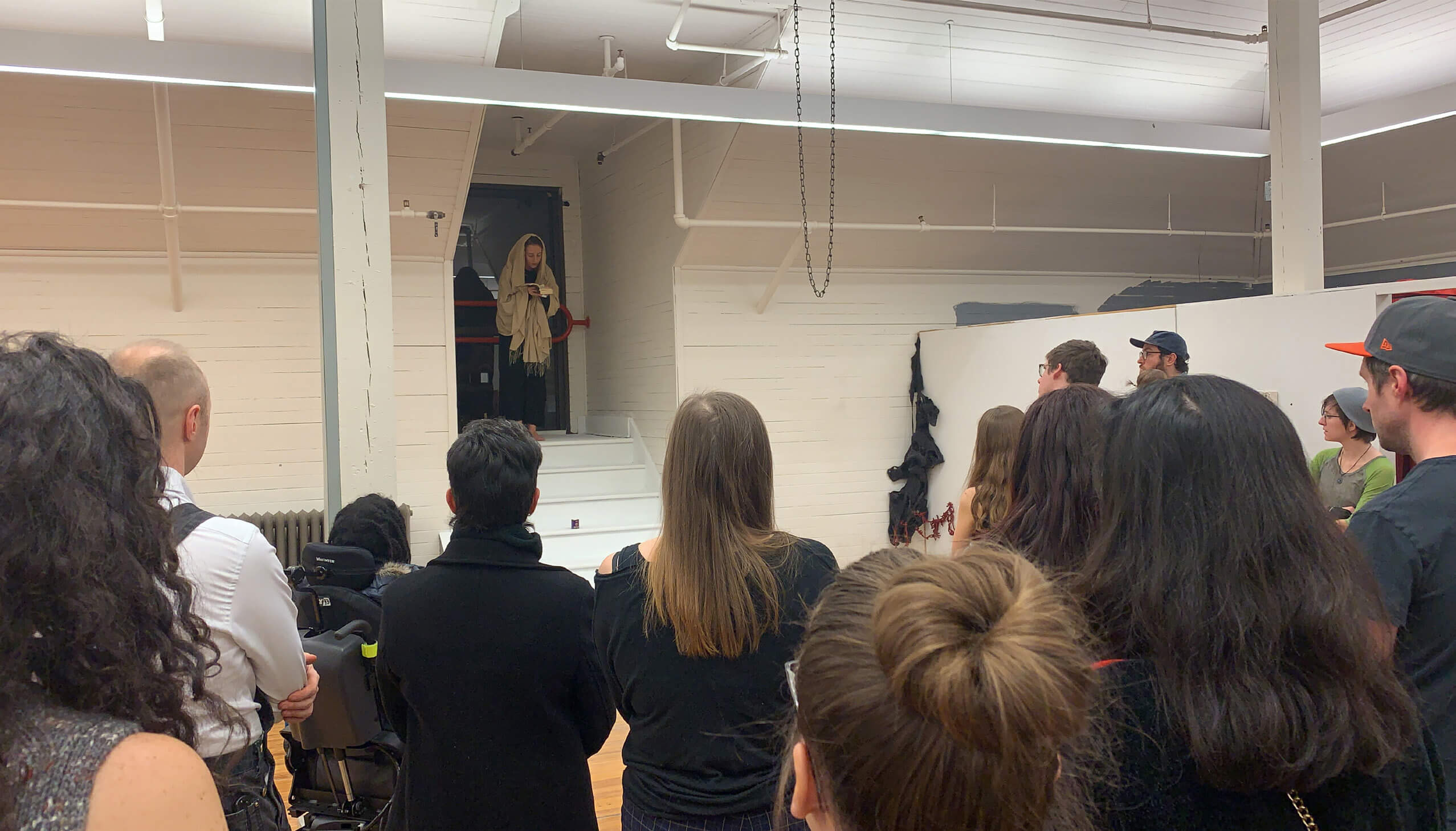

MEIRAV ONG’s work is rooted in ritual, often addressing grief or trauma through object-making, community-based social justice work, and performance. Mourner’s Kaddish (My Mother’s Yahrzeit) blurs the boundaries between art and life as Ong addresses the Orthodox law governing who can recite Kaddish and how. In her community, she was unable to recite Kaddish within the prescribed all-male minyan or without a male voice present. In this piece, Ong publicly recites Kaddish for her mother for fifty-six minutes, thus, she notes, “My mourning taught me that as a woman, a Jewish woman, to speak my full voice is a radical act.” She recalls that as she repeated the prayer over and over on the anniversary of her mother’s deathday, “I let myself feel rage, softness, and all the shadows in between as if to make up for lost experiences of reciting this prayer.” She observes that the performance ended when she realized that “no length of time would give me back my silenced voice from my first year in grief.”

Meirav Ong. Mourner’s Kaddish (My Mother’s Yarztheit), 2018. Stills from performance 00:56:00.

Mourner’s Kaddish was performed in Syracuse, New York, on December 8, 2018, Rosh Ḥodesh Tevet, the night of my mother’s z”l fourth Yahrzeit. It was the first time I recited Kaddish alone and without a minyan. I repeated the prayer over and over as an offering to my voice. Reciting Kaddish while “performing” for an audience triggered memories from my year of mourning reciting Kaddish in a minyan that ignored my voice. The audience, unaware they had an active role to respond “amen,” left my voice continuing to be unanswered, heightening my feelings of loneliness. For an hour, I let myself feel rage, softness, and everything in between as if to make up for lost experiences reciting this prayer. The performance ended when I realized no length of time would give me back my silenced voice from my first year in grief.

Meirav Ong. Wrapping I, 2020. Still from performance.

These ritual sketches are adaptations of an existing language of ritual objects—like the knots of tzitzit and the wrapping patterns for tefillin—testing how they feel in my body, wondering if it will ever not feel foreign. I realized in these initial sketches that I’m not interested in feminizing practices intended for male-identifying bodies. But I yearn to be adorned and wrapped in spiritual garments. I feel both exposed and unseen without a set of spiritual armor. Ritual sketches are adaptations of an existing language of ritual objects: "tzitzit" knots and "tefillin" wrapping patterns. I am testing how they feel in my body, wondering if it will ever not feel foreign, and learning from these sketches that I’m not interested in feminizing practices intended for male-identifying bodies.

MEIRAV ONG (she/they) creates sanctuaries for listening to elevate voices marginalized within patriarchal systems of religion through textiles, clay, sound recordings, and body-based performances. Ong has exhibited at The Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, New Jersey, the Fowler-Kellogg Art Center in Chautauqua, New York, Women Made Gallery in Chicago, Illinois, and The Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, among others. She’s the recipient of grants to the Vermont Studio Center, Penland School of Craft, Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts, and Chautauqua School of Art, among others. Ong holds an MFA in Fiber from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a BFA from the University of Michigan and is currently based on Canarsie and Munsee Lenape lands (Ridgewood, New York). Her work can be viewed at www.meiravong.com and on Instagram @meiravi.

RUTH SERGEL is a Jewish American artist living and working in Berlin. In projects such as Chalk and Gaza Ghetto, Sergel investigates the degree to which she is “living in alignment” with her own values. Sergel’s work often takes the form of memorial and of bearing witness to the inequities of power. Both Chalk and Gaza Ghetto embody the ideals of Jewish teaching at its most humanitarian core. Sergel’s embodied, empathetic, and performative projects test both her faith and her sense of righteousness, as she asks herself questions of what is morally right or justifiable and makes herself accountable to the answers via her social justice-focused artwork. Chalk was prompted by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York, where, on March 25, 1911, 146 young workers, most of them immigrants, most of them women and girls, perished in the fire.

Since 2004, on each anniversary of the infamous blaze, participants fan out across New York City to inscribe in chalk the names and ages of the Triangle dead in front of their former homes. A flier describing the history of the fire is posted in English, Chinese, and Spanish. Sergel states that “Chalk is a purposely ephemeral memorial. If we do not remember, if we are not willing to take action in the streets, then the memorial will not exist.”

The impetus for Gaza Ghetto came in 2014, when, Sergel notes, “Israel’s Operation Protective Edge (the Gaza War) was in full swing.” Sergel recalls thinking that “there is no way forward if we cannot recognize the fundamental humanity of the Palestinian people.” In response, she wrote the name of each Palestinian killed in Gaza on her arm, made a photograph, and posted the image to social media. Sergel states that “art requires the participant to risk. In an immediate and physical manner, the individual has to choose to act. It is the risk we are warned against: transforming our imagination into substantive action in the physical world.” Yet, this is the task of both artists and Jews; to make difficult statements of conscience in the face of extreme political climates of any kind.

Photo by Manfred Reiff

RUTH SERGEL is an artist who lives between NYC + Berlin. For more on her work, please visit her website at www.streetpictures.org.

CHELSEA STEINBERG GAY is a sculptor and performance artist whose work often addresses “the universal experience of remembering, identifying, and protecting.” Her disparate projects lean heavily on her Brooklyn Jewish upbringing and a strong sense of justice. A number of her projects address the trauma of failed social policies with materials that evoke the body—food, emergency blankets, diapers—"drawing policy and statistic into an uncomfortably intimate context.”

Chelsea Steinberg Gay. HELP YOURSELF (PROCESSED II), 2020. Cake pops molded into internment camp tents, graham cracker crumbs, photo tent. 48 in. x 48 x 48 in.

Does genocide have a rhythm? A pendulum we can feel swinging from pole to pole? Can we sense it coming?

The term was coined in 1943 by the Jewish Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin who combined the Greek word “genos” (race or tribe) with the Latin word “cide” (to kill).

After witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust, in which every member of his family except his brother was killed, Dr. Lemkin campaigned to have genocide recognized as a crime under international law.

His efforts gave way to the adoption of the UN Convention on Genocide in December 1948, which came into effect in January 1951.

Article 2 of the convention defines genocide as “any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such”:

• Killing members of the group

• Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

• Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

• Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

• Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group

Chelsea Steinberg Gay. IN PROCESS, 2019. Plastilene clay. 6 in. x 2.5 in. x 2.5 in.

Model of dormitory tent from one of the Trump administration’s Tent City internment camps, model for artist multiples cast from cake pop embedded with fiberglass strands.

Process, processed

To alter or modify

To cognitively absorb

Processed ingredients

Processed information

Does processing precede consumption or do we consume mindlessly?

Families “processed” in DHS facilities.

Is genocide a process we can see?

A process we can acclimate to?

CHELSEA STEINBERG GAY (she/her/hers) (b. 1986, Brooklyn, New York) is a sculptor and performance artist whose works look at how displaced or marginalized communities create, alter, or mobilize folklore, legends, and the occult as a means of protection and perseverance. A multidisciplinary artist, her works involve drawing, photography, video, sound, and performance, fabricated in whatever materials most appropriately realize each piece. She holds an MA in Jewish Art and Visual Culture from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, a BFA in Sculpture from SUNY Purchase College, and is an MFA Fine Arts candidate in Parsons School of Design’s class of 2023. Her work has been included in numerous domestic and international exhibitions and private collections.

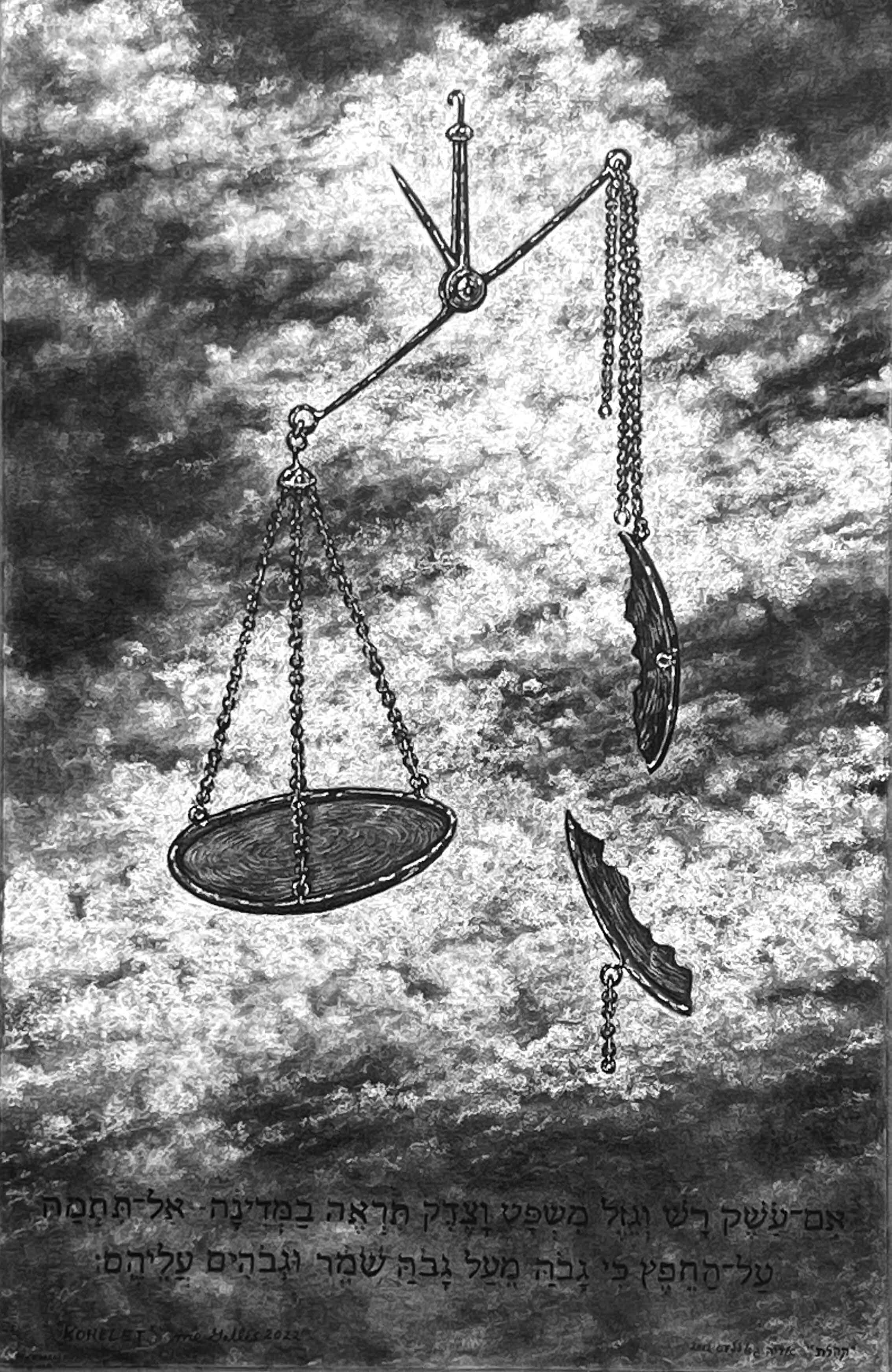

In the whole of the Tanakh I find the book of Ecclesiastes a profoundly empirical Jewish exegesis on the concept of justice. Quotes from that book are often repeated in literature and song. The phrase that intrigues me the most is Kohelet 5:7.

If you see in a province oppression of the poor and suppression of righteousness and justice, don’t be shocked at the fact; for one high official is protected by a higher one, and both of them by still higher ones.

Many hackneyed representations of a skewered scale of justice exist, presenting an unbalance tipped against justice, blind as it may be. As a Jewish artist, I envision the scale not merely unbalanced, but completely broken, floating, like the Flying Dutchman in the sky. Humans murder humans, turn cities into blood-soaked rubble. While their mouths speak of justice, their hands are busy killing.

― Arie Galles

Arie Galles. KOHELET/ECCLESIASTES 5:7, 2022. Charcoal and conte arches. 30 in. x 19 in.

ARIE GALLES was born in 1944 in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. He received his BFA in 1968 from the Tyler School of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, and MFA in 1971, from the University of Wisconsin– Madison. He taught at UW-Madison, Southern Methodist University, the School of Visual Arts in New York, University of California, San Diego, and Fairleigh Dickinson University, in Madison, New Jersey. His works have been widely exhibited, including solo multiple shows at the O.K. Harris Gallery, in New York, and the Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, in Chicago. He has also exhibited and lectured in Canada, England, and Poland. Notable works are his Reflected-Light Paintings and the drawing suite, Fourteen Stations/Hey Yud Dalet. Arie has completed his book, Drawing with Ashes, based on ten years of journal entries during the creation of this suite. Galles is at work on his latest series of paintings, Chromatic Modulation, and is currently artist-in-residence and professor emeritus of Painting/Drawing at Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, California.

Susan Sontag was a pioneering art critic and writer who helped to define the mid-century modern era. Sontag was among the only women among the 1960s world of New York Jewish intellectuals that included the powerhouse critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. In her seminal book from 1966, Against Interpretation, she observed that "The aim of all commentary on art should be to make works of art— and by analogy, our own experience—more, rather than less, real to us.”

As we think about how art can speak to the most important issues of the day, as it is framed within a commitment to justice, Sontag’s words take on a deeply important task; she asks us to let art do its work, to make life as real as possible, and to apply our sense of ethics to all that artists might ask us to consider. This is the difficult work that we are asked to do as artists and Jews seeking justice, to stand by our beliefs. As parashat Shoftim implores, “Justice, justice, shall you pursue,” and I would add, even when it may be difficult.

Douglas Rosenberg

University of Wisconsin–Madison