Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

THE PROFESSION

My forthcoming book, The Object of Jewish Literature: A Material History, uses key terms related to materiality as a way of narrating literary history. Its origins may be found in an antiquarian shop in Krakow’s Kazimiercz neighborhood. While visiting Poland for the first time in 1998 I came across an olivewood-bound photo album from Jerusalem, produced by the A. Lev Kahane Press in the early twentieth century, and likely brought back by a tourist or religious pilgrim. The album contained a collection of cards with color-tinted drawings of holy sites on one side, and pressed flowers on the other. The captions appeared in Hebrew, Russian, English, French, and German. Many of the dried flower petals we e remarkably intact, but the Hebrew had been scratched over in pencil on nearly every single page. I knew of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Crafts, founded in Jerusalem in 1906, and recognized the general style and pedigree. But holding this particular book in my hands, and purchasing it from the owner for 90 zloty (his name was Jacek Barnas, I still have the signed original receipt, about $50 today, adjusted for inflation), was a foundational moment for me as a scholar, a Jew, and an artist. The experience fueled my sense of the book as a mutable object that travels—among languages, countries, and owners.

The experience fueled my sense of the book as a mutable object that travels— among languages, countries, and owners.

Since then, I have wandered in European flea markets filled with prewar detritus, including household items and other personal possessions such as clothing, kitchenware, and toys. Some of this vast material sea is identifiably Jewish— books marked by the Hebrew alphabet, or items marked by their ritual function. Encountering these objects expanded my sense of what material culture has meant for European Jewish life. At the same time, it also hinted at a kind of historical tension: so many objects, so few Jews. The gap between the destruction of Jewish life—towns, people, and their stuff—and the enormous amount of leftovers littering Europe has spurred me to consider how materiality has figured in Jewish literary expression. And in order to really understand why materiality matters, it wasn’t enough to write a book; I had to make one as well.i In recent years I have engaged in hands-on printing and bookmaking, always trying to replicate some of that initial haptic wonder of finding an olivewood photo album that once belonged to someone else.

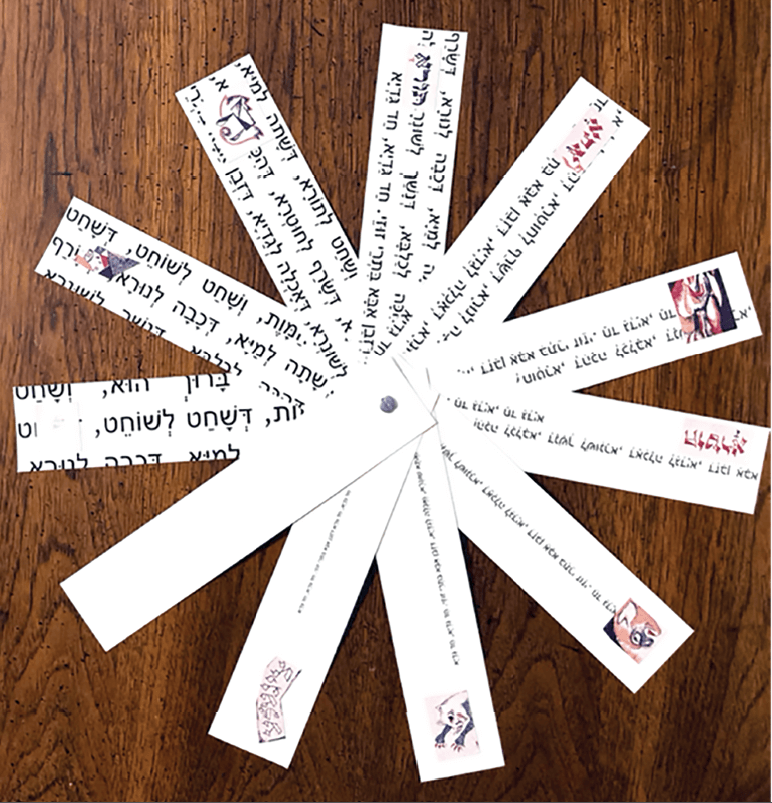

Barbara Mann. Khad Gadye Pesach Benchers, 2019. Mixed media artist book.

My Khad Gadye Pesach Benchers (2019) is an artist’s book inspired by the Russian Jewish artist El Lissitzky’s Khad Gádye (1919)—an essential book in the history of Yiddish print, the history of modern Jewish literature and—given Lissitzky’s stature and influence as an a tist, designer, and typographer—possibly the entire trajectory of twentieth-century art. Now that is a lot to put on a book featuring a nonsense song about animals, not even a “real” part of the Haggadah, and often viewed as a kind of add-on, whose melodic concatenation of verses linked in associative style was guaranteed to keep the kids awake. Lissitzky’s book is a dazzling amalgam of avant-garde forms and folkloric motifs, a tour-de-force statement of aesthetic and political possibility. My own project is more modest: a single limited edition of ten, enough to share around a family seder. Conceptualizing and creating them, at home and in New York’s Center for Book Arts, allowed me to experience the physical side of creation—to face and solve design quandaries, choosing materials to suit my own artistic aims, while creating books that would be pleasing to hold and easy to read at the end of a long Pesach meal.

The fastener at the bottom allows for a windmill or fan-form that opens to mimic the cyclical quality of the song’s violence.

I disassembled the components of the pages of Lissitzky’s book—the letters, the Yiddish, the Aramaic and the Hebrew; the colored illustrations; the colophon and dust jacket—into their constituent material components, and rejiggered them in collage fashion on each slender bencher page. The text itself of the original song appears in progressively larger fonts, which eventually bleed off the page, uncontained. The fastener at the bottom allows for a windmill or fan-form that opens to mimic the cyclical quality of the song’s violence. I made the cover using a technique called “blind emboss,” where type is set and paper is run through a letterpress printer without any ink on the roller. It may be read through touch, almost like Braille, enhancing the tactile quality of each bencher. I also corrected some of the spelling errors in Lissitzky’s book.ii

Making stuff, using my hands to create books and prints, enriches my scholarship. This has been especially the case for my project on materiality and literary history, but I believe it could pertain to other kinds of work as well. For one thing, bookmaking is meditative. It allows for “slow time” to process my research’s theoretical frame, while my hands are busy doing something automatic (sewing or gluing a seam, measuring or cutting paper), or experiencing the tactile qualities of various materials— their weight, texture, viscosity, and feel to the touch. I believe these kinds of activities promote the serendipitous connections that are sometimes elusive when focusing directly, more consciously, on the materials of one’s research—connections that often prove essential to the work as a whole. Secondly, figuring out how different pieces of the book relate and fit together provides sensory data that become a kind of template for the conceptual frame of my research—allowing me to know what piece should come first and what should follow, what can be cut or deleted altogether, and where it all ends. Endings are especially challenging: How do you know when you are done with a monograph, an article? What is enough and where do you stop? Making physical books—which have a relatively clearly defined beginning, middle, and end—has helped me better understand the contours and shape of my own scholarship. And while the finished composition may get sent to the publisher or journal long before I can actually hold it in my hands, the promise of the olivewood album, changing hands and accumulating new meaning over time, remains before me on the desk as I write these words.

.

BARBARA MANN is professor of Cultural Studies and Hebrew Literature and the Chana Kekst Professor of Jewish Literature at The Jewish Theological Seminary. She is the author of Space and Place in Jewish Studies (Rutgers University Press, 2012) and A Place in History: Modernism, Tel Aviv and the Creation of Jewish Urban Space (Stanford University Press, 2006). The Object of Jewish Literature: A Material History (Yale University Press, 2022) has been supported by fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

iSee my “The Scholar and the Bookmaker: On Encountering the Material Side of Things,” In geveb (March 27, 2019), https://ingeveb.org/blog/the-scholar-and-the-bookmaker.

ii(cf. Samuel Spinner, “Reading Jewish,” PMLA 134., no. 1 (2019): 150–-156.)