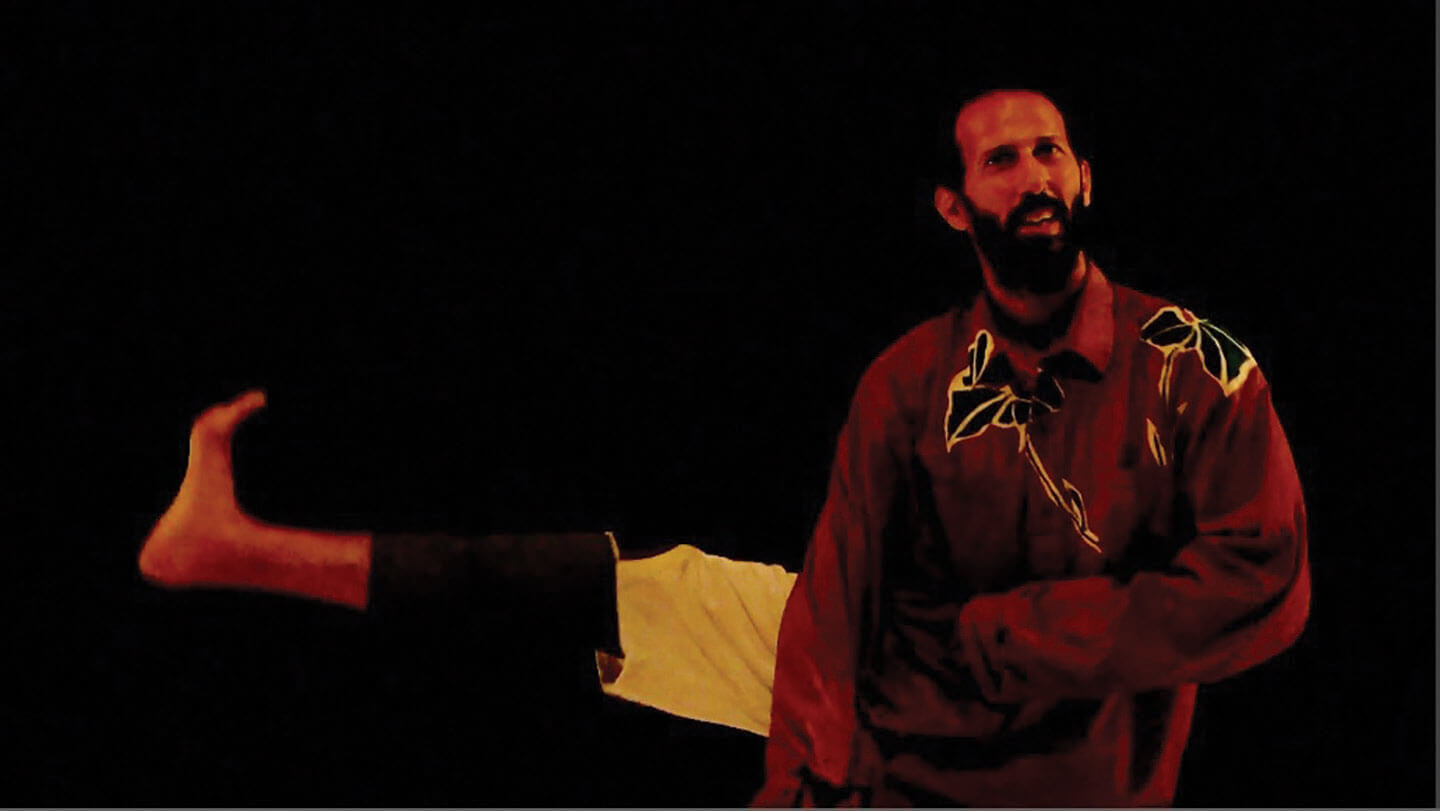

Above: Detail from Yair Barbash performing in Ka’et Ensemble’s Bli Neder. Screenshot by the author.

DANCE

Zionism is a movement of Jewish return: to the Land of Israel—but also to the Jewish body. Whether it was Max Nordau’s advocacy of “Muscle Judaism”; Y. H. Brenner’s contempt for the Luftmenschen; Micah Berdichevsky’s appeal that “Jews must come first, before Judaism”; Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook’s fusion of the physical and the spiritual; or A. D. Gordon’s call for the Jewish people to bind themselves to its soil and culture through physical labor—Zionism viewed the body as the new locus for Jewish being.

Critical Jewish scholarship has often questioned the sincerity of the Zionist call to return the Jew to her body. The claim—articulated most eloquently and often by Daniel Boyarin—goes something like this: since talmudic times, the Diaspora has offered the Jew a fully embodied Judaism, albeit of a pudgy, sissy kind (when it comes to males). Thus, the Jews didn’t need Zionism then—and don’t need now—to return to their bodies, as they never left them.i

Eyal Ogen performing in Ka’et Ensemble’s Bli Neder. Screenshot by the author.

Contra this claim, I want to suggest that Zionism does, in fact, return the Jew as a Jew to her body in a deeper, more thoroughgoing way than the Diaspora does—or ever can. But first we must ask, What does it mean to inhabit one’s body as a Jew? Doesn’t every Jew, by definition, do that? The short answer is: no. A Jew may be fully embodied as a person without being embodied as a Jew, fusing her corporeality with her Jewish consciousness, with her identity as a Jew. So perhaps this embodiment qua Jew transpires during the observance of any and every mitzvah that is geared towards, or involves, the body, such as immersion in a mikveh, dwelling in the sukkah, observing the laws of niddah, eating, relieving oneself, and so forth? To be sure, these mitzvot offer opportunities for Jewish embodiment. But each of these acts is circumscribed in some way. Some of them involve the whole body but are limited in duration. Others may be consistent over time, yet their scope is limited: they involve only part of the body. In the Diaspora, the Jew becomes full-fledged, boundless corporeality qua Jew when she endures physical oppression because of her Jewish identity. In the words of Jean Amery, describing his experience of being hit by a foreman in Auschwitz—and hitting him back: “I was my body and nothing else.” He continues, “My body, when it tensed to strike, was my physical and metaphysical dignity.”ii Zionism, too, offers variations on this theme: being physically attacked as an Israeli Jew offers me a full-bodied Jewish experience, and I can even don an IDF uniform and preempt attack, asserting my own ability to confront a non-Jew via the body. Yet Zionism can offer a much richer sense of full-fledged Jewish physicality, one that gets at the deepest recesses of Jewish existence. I have experienced this bodily—not through physical labor, as classical Zionism would have liked, but through dance at the Between Heaven and Earth dance center in Jerusalem. In the words that follow, I will examine embodiment in two brief pieces of the Between Heaven and Earth’s professional Ka’et Ensemble’s 2018 performance, Bli Neder (Without taking a vow).

Immediately after expressing his desire to speak about “self-fulfillment,” Yair Barbash lies down, and Yuval Azoulay kicks him in the abdomen. At once, Barbash and the other two dancers all react as if they have been kicked in the same spots, evoking the rabbinic adage that all of Israel is responsible for one another.iii Eyal Ogen slowly rises and begins chanting Exodus 21:2–6, a passage about the Israelite who sells himself into slavery because of debt, while Ogen’s physical movements offer a stunning visual interpretation of—and response to—the trop (cantillation) that he chants. His dangling smile not only evokes the spectator’s laughter, it brings us into the hollow inner world of the person who has foregone his freedom because of financial obligations: his being has been reduced entirely to his potential for physical production, and his simple, empty smile reveals that he lacks the requisite spiritual depth to experience his reduction to pure physicality as an afront to his being. Barbash, in the meantime, fades to the background and returns again to the fore, occasionally interrupted by spastic moves, convulsing as if his body has endured shock. Suddenly, he interrupts Ogen, correcting his pronunciation of the word “and she shall go out” (Exodus 21:3). What follows—familiar to anyone who has been in a synagogue when the Torah reader has been corrected and tries, unsuccessfully, to correct his misstep and reread the passage—is an exchange of blunted aggression as Barbash, with voice and hand movement, precipitates a combination of defensiveness and desperation on Ogen’s part.

Yair Barbash performing in Ka’et Ensemble’s Bli Neder. Screenshot by the author.

With all four dancers on stage, bouncing gently up and down, Barbash begins a monologue, quickly changing subjects. Each of the other three dancers commences a monologue simultaneously, with Ogen again chanting the passage from Exodus 21. Suddenly, Barbash interrupts his own monologue to correct Ogen’s pronunciation once more, issuing forth a voice that sounds more like an animal than a person. All players pause, only to resume their monologues. But within seconds, Azoulay interrupts Ogen with his own “meeh,” silencing everyone. As all four resume their monologues, Ogen counters with his own “meeh.” As they all begin to “meeh,” what ensues is men making a parody of themselves—of their insistence on correcting their fellow and, in so doing, competing to see who can offer a more faithful, punctilious rendering of the written word. The synagogue is thus transformed into a barn in which animals vie for superiority. For over forty seconds, each player “meeh”s, using hand signals to entice the audience’s participation, until suddenly Hananya Schwartz bellows forth a “meeh” that draws his body down and his arms up, silencing the crowd and the other three dancers. As he glares at each of the dancers and walks threateningly towards each of them, it is clear that he has outpowered them. They stare meekly as he stomps up and down, child-like in demeanor but unmistakably adult in force. Chanted words of Torah have been transformed into raw vocal power and bodily energy.

Bli Neder captures the full ripening of Jewish embodiment that Zionism enables, with the dancers giving bodily expression to a complicated nexus of issues: the words of Torah as they play out between individuals and in the context of community; the spoken word, with its rough edges and its relationship to a pure physicality that borders on animality; and broader human issues such as freedom, physical labor, loneliness, companionship, and parent-child relationships, as each receives expression in the particular context of Jewish culture and identity. The involvement of the audience and the rawness of the voices of the dancers’ parents in voice-overs reveal that the bodily expression of the dancers is inextricably linked to the embodied reality that Zionism offers—and perhaps also imposes on—the Jews who take part in it. What is at stake in these competing iterations of Jewish embodiment is a deeper disagreement about the very possibility of a holistic Jewish identity.

It is hardly coincidental that the model that portrays authentic Jewish embodiment as diasporic views Jewish identity itself as a matter of hybridity, for personal identity as such is fractured and intersectional in nature.iv But Zionism’s promise to allow the Jew to return fully to her body qua Jew is predicated on the possibility of an immersive Jewish identity, even as it accepts the composite nature of that identity. Bli Neder shows how Zionism, with all of its flaws and shortcomings, fulfills this promise.

.tmb-medium.jpg?sfvrsn=9ae9506_1)

LEON WIENER DOW heads the beit midrash at Kolot and teaches at the Secular Yeshiva of Bina in Tel Aviv, the Schechter Institute, and Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion. His most recent book, The Going: A Meditation on Jewish Law (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) won a 2018 National Jewish Book Award, and his Your Walking on the Way was published by Bar Ilan University Press (2017, in Hebrew).

i See, for example, Daniel Boyarin, Unheroic Conduct: The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man (University of California Press, 1997); Boyarin, Carnal Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture (University of California Press, 1995), especially chapter 7; Boyarin, A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), and the essays by Howard Eilberg-Schwartz, Boyarin, and David Biale in Howard Eilberg-Schwartz, ed., The People of the Body: Jews and Judaism from an Embodied Perspective (State University of New York Press, 1992).

ii Jean Amery, At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities (Schocken, 1986), 91.

iii Sifra Be-hukotai 7:8.

iv Jonathan Boyarin and Daniel Boyarin, The Powers of Diaspora: Two Essays on the Relevance of Jewish Culture (University of Minnesota Press, 2002).