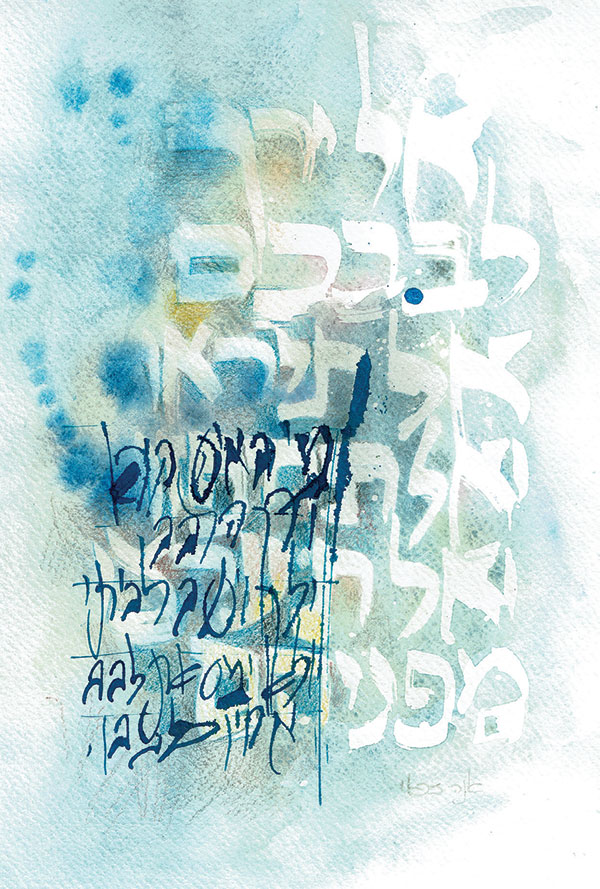

Above: Detail from artwork by Anna Zakai. Courtesy of the artist.

The Hebrew Bible represents emotion and affect as embodied phenomena in a wealth of passages. A verse from Deuteronomy 20, the most extensive collection of laws about warfare, is a case in point:

ויְסְָפוּ הַשֹּׁטְרִים לְדַבֵּר אֶל־הָעָם ואְָמְרוּ מִי־הָאִישׁ הַיּרֵָא ורְַךְ הַלֵּבָב ילֵֵךְ ויְשָֹׁב לְבֵיתוֹ ולְאֹ ימִַּס אֶת־לְבַב אֶחָיו כִּלְבָבו

And the overseers shall speak further to the troops and say, “Whatever man is afraid and faint of heart, let him go and return to his house, that he not shake the heart of his brothers like his own heart.” (Deut 20:8, Alter translation)

Artwork by Anna Zakai. Courtesy of the artist.

Which phenomena, among those variously addressed by the Bible and rabbinic literature, were considered emotions within their respective cultures is a complicated question, inter alia because of a lack of related definitions and overarching categories in the sources. Nonetheless, our passage is a pertinent object of inquiry: its context evokes dread through its imagery, names fear through five emotional terms, and aims at dispelling warriors’ apprehension by means of a military oration (vv. 1:3–4). Furthermore—argued from an outside perspective and with the foundational idea of cognitive and emotional embodiment theories (found, for example, in the 2015 edition of the Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology)—Deuteronomy 20 represents fear as embodied, because it addresses the emotional and somatosensory experience of the Israelites before battle. It does so by situating it in their immediate physical and social environment.

Let us look at how our verse constructs the relationship between the emotion of fear, this male self (i.e., body-and-mind), and the battlefield. A fruitful insight can be drawn from historical emotion research, which broadly tends to view emotions either as going on in the body, as if the latter were bounded and autonomous, or between bodies, as if the latter were porous, merging with their environment. Qua body-and-mind, the addressee of our military oration is inhabited by fear of the enemy. Although his apprehension is elicited by the external threat, he is described as bounded, with an emphasis on his being afraid and faint of heart (an emotional tendency? a character trait?). However, his fearfulness might be contagious, his comrades are potentially permeable, and fear might become a transpersonal emotion.

Let us now consider how early rabbis refigured this emotional body-and-mind inherited from the Torah. A midrashic unit in the Mishnah tractate Sotah expands on Deuteronomy 20:8 thus:

ויספו השטרים לדבר אל העם ואמרו: מי האי' הירא ורך הלבב ילך וישב לביתו. ר' עקיבא או' הירא ורך הלבב כשמועו שאינו יכול לעמוד בקשרי המלחמה לראות חרב שלופה. ר' יוסה הגלילי או' הירא ורך הלבב שהוא מתיירא מן העבירות שביד.

And the overseers shall speak further to the troops and say, “Whatever man is afraid and faint of heart, let him go and return to his house” [Deut 20:8a]. R. Akiva says, “Whatever man is afraid and faint of heart: just as it sounds. He cannot stand in the battle-ranks or see a drawn sword.” R. Yose the Galilean says, “The man who is afraid and faint of heart: that is one who is afraid [of dying] on account of the transgressions he has committed.” (M. Sotah 8:5, abridged)

The literal interpretation, attributed to R. Akiva, represents the environment as impinging on the body through spatial perception and vision.

The literal interpretation, attributed to R. Akiva, represents the environment as impinging on the body through spatial perception and vision. Both the biblical and Akivan Israelites are constructed, thus, as permeable and changed by the environment. The Akivan emotional body-and-mind seems to invoke the representation of the battlefield crafted by the Mishnah a few pericopes before the one above:

אל ירך לבבכם אל תיראו ואל תחפזו ואל תערצו מפניהם. אל ירך לבבכם מפני צהלת ס()[ו]סים וציחצוח חרבות. אל תיראו מפני הגפת תריסים ושיפ()[עת] הק(ו)לגסים. אל תחפזו מפני קול הקרנות. ואל תערצו מפני קול הצווחה.

Let your heart be not faint. Do not fear and do not quake and do not dread them [Deut 20:3b]. “Let your heart be not faint”—at the neighing of horses and the shining of swords; “do not fear”—at the clashing of the shields and the trampling of the caligae; “do not quake”—at the sound of the horns; “do not dread them”—at the sound of the shouting. (M. Sotah 8:1)i

How dreadfully loud become the biblical enemies in this rabbinic expansion! By placing the emphasis on perception, mostly on audition, the latter passage grounds the Israelite’s experience even more intensely in the outer world than the Torah and R. Akiva’s dictum in the midrashic dispute do. The emphasis on hearing, I’ll venture to suggest, can even succeed in grounding the experience of the text’s audience, ancient and modern,

in the soundscape of a (Roman?) battlefield. The bluster of the enemies resonates not only through the literary images, but also through the auditive body of the text (its rhythm, alliteration, and assonance), up to the audience’s mind (have you read the text out loud?). The emphasis on the environmental and perceptual elements is starkly countered, in the dispute, by the figurative interpretation, attributed to R. Yose the Galilean, which constructs the male self as bounded and withdrawn from the world into his consciousness. Here, the embodied fear of the biblical and Akivan Israelite becomes a matter of piety, related to the Israelite-God relationship and the self-conscious emotion of guilt, without reference to any bodily underpinnings. This male self is absorbed by judgment of his own conduct. He is not disembodied, but uninterested in or unaware of his embodiment, to the extent that the very concrete biblical enemy turns, in this midrashic expansion, into an internal one. Perhaps not less noisy an enemy than that clashing and trampling and shouting on the battlefield.

Using the conceptual lens of embodied emotion, we can see that this midrash does not only present two different interpretations of a biblical verse, but two distinct anthropological attitudes towards the emotional self. As we continue to read these sources in this way, what other ways of constructing the emotional body-and-mind (also nonmale and non-Jewish) will we be able to detect?

Photo by Giulia M.

ELISABETTA ABATE is a research associate at the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities, where she is contributing to compiling the first philological dictionary of Qumran Hebrew and Aramaic (Hebräisches und aramäisches Wörterbuch zu den Texten vom toten Meer). Dr. Abate is also an internationally certified teacher of the Feldenkrais® Method, her constant source of inspiration in matters of embodiment.

i You can read this pericope (M. Sotah 8:3) in the best Mishnah manuscript.