Above: Hand-written letters of bacteriologist Waldemar Haffkine concerning his research on cholera in India during the late nineteenth century. Photo taken by the author at the Haffkine Archive, National Library of Israel.

I would like to introduce you to the Ottoman Jews: not the ones you’ve heard about; the ones who have been forgotten, the remnants of whom I have been reading about for the last two years in the archives.

Two young men who stocked animal bones, nails, and horns in a store. A man who killed and dismembered his friend while gambling. Yako the arsonist. Orphans left in front of synagogues. “Mazalto the Insane” who was kept in the basement of a prison. A convert to Christianity who was beaten up by the locals. Avram who sold erotic photos in public. The head of a Jewish community who sold fake official certificates. Cholera-stricken Jews who were sent to live in tents on a mountain.

“Deviance and marginality are powerfully indicative of political authority and of norms,” writes historian Arlette Farge.i In the late Ottoman Empire, the public realm was the locus for defining and monitoring the appropriate central type and the socially abnormal and deviant bodies. As the public awareness of marginals intensified, the body became the site both for the expression of alternative social identities and of intervention on which power relations were carved. In my research, I focus on the Jewish marginals of nineteenth-century Izmir from a corporeal perspective.

Over the last two years, I have been conducting archival research in Turkey and Israel to rescue marginal but ordinary, invisible yet noticeable historical bodies from their isolation by linking them to spaces of everyday life. I focus on the sewage running down the streets of Izmir and the lives formed around it. I concentrate on unruly bodies, the vilest trades, and filthiest portions of the city, which were continually remade and refined along modernizing agendas. I am after different realities. In the archives, different realities unfold.

Russian words from my childhood, spasibas and kharashos, popped up every time I started speaking Hebrew.

I spend months reading police reports, court records, communal registers, newspapers, and letters in Turkish, Ottoman Turkish, Ladino, Hebrew, English, and French. Six languages, four different scripts. Kafs started to look like swans and dalets as sevens. Russian words from my childhood, spasibas and kharashos, popped up every time I started speaking Hebrew. When I spoke Turkish, my sentences were formed according to the word order in French. Just like the archive, my brain was a microcosm of past lived experiences, a mysterious place born out of a moderately coordinated chaos.

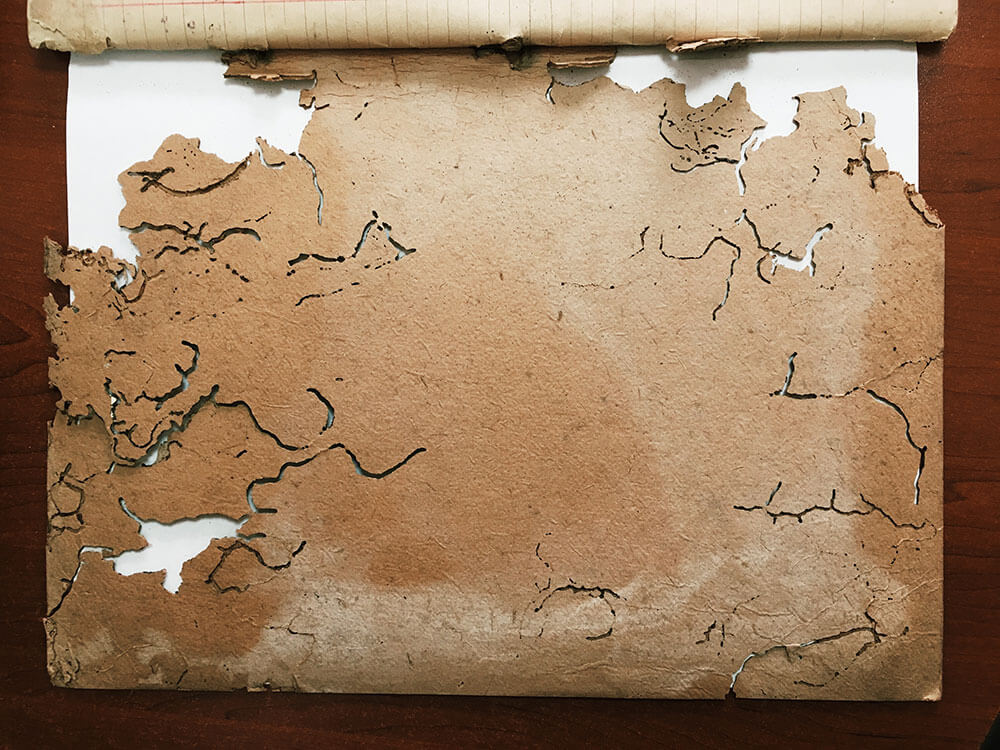

Damaged notebooks found at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, probably eaten by a bookworm. Photo by the author.

My days at the Ottoman State Archives in Istanbul were fueled by cups of Turkish coffee followed by sleepless nights wondering what can be gleaned from 150-year-old documents about the lives and deaths of marginal Jews. While tracing the irregular in Istanbul, people told me that I do not look Turkish. They told me that I look like a German, or an American. Men asked if I can “really” read Ottoman Turkish. People complimented my perfect command of Turkish. People commented on my Izmirli accent. People made jokes about the horrible yet popular stereotype of “beautiful Izmirli women.”

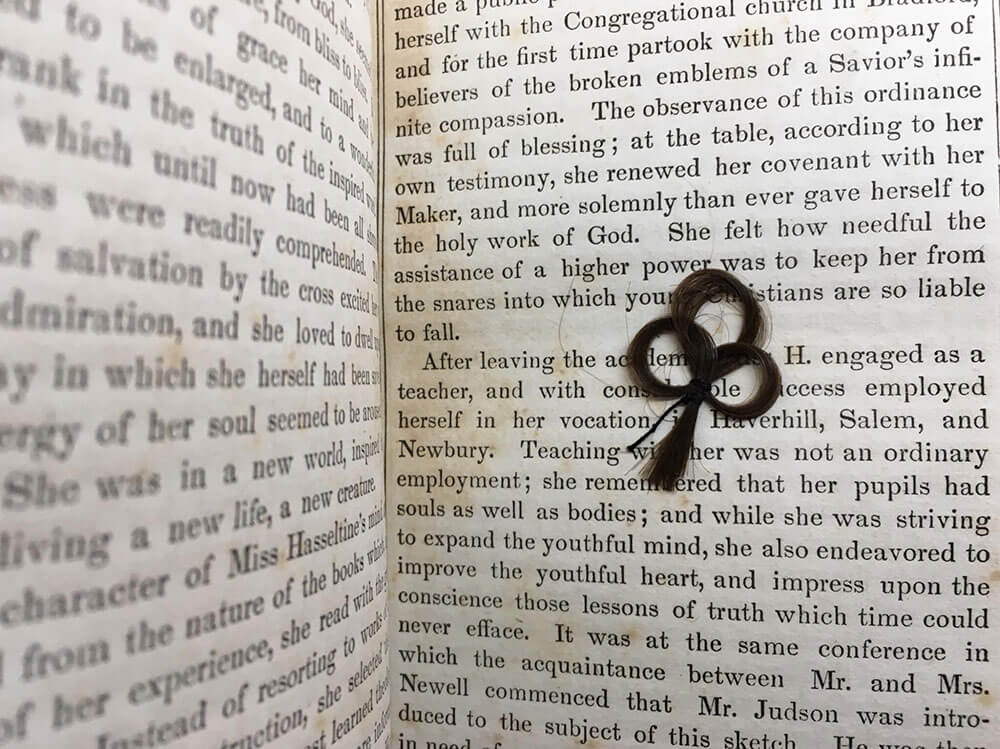

In Jerusalem, I spent my days at the National Library, the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, and the Ben-Zvi Institute. I ate hummus for all my meals. I got bitten by a bug seventeen times while reading a charity register. I found a lock of hair inside an old book written by Christian missionaries. Strangers asked if I can find their Izmirli grandparents’ houses in Izmir. People asked if I was Jewish. People asked if my family is from eastern Europe. People asked me to comment on Turkey-Israel relations. They commented on my “funny” word choices when I spoke Hebrew and strong ings when I spoke English.

Lock of hair which found inside an old book at the National Library of Israel, written by Christian missionaries. Photo by the author.

In Istanbul and Jerusalem, in one way or another, people asked me, “Who are you?” Just like the marginals from the archives, I was something of a curiosity that required definition.

I could have told them about myself and my great-grand-parents’ past lives in Algiers, Corinth, and Damascus, and how their paths crossed in Izmir. I could have told them the languages they spoke and dreamed in, things they celebrated and mourned, their eclectic food and weird sense of humor. Perhaps a detailed examination of my personal history would help strangers to understand and also justify my interest in the abnormal. Probably, marginals of my hometown had to explain themselves to strangers, too. Maybe they decided it is futile to explain, just like I did.

In the last two years, my research question changed many times. I talked about my research in eight different cities, shared the stories of marginal Jews of Izmir in Jewish Studies and Ottoman Studies circles. I carried their stories with me during my visits to my family home in Izmir, coming full circle.

My experience of meeting with new people means saying my name a couple of times and explaining its pronunciation. Some try, some do not care, and a few decide to call me Joanne. It is hard to have a name that starts with a sound that does not have an equivalent in most languages. How does one explain a sound that does not exist in a language? How does one tell stories of marginal bodies that no longer exist in the world?

I still find it quite interesting that it took me five years to realize that my research was also a quest for my identity and placelessness that I embody and carry wherever I go.

In Turkish, the letter c is pronounced like the j in jam.

CANAN BOLEL is a doctoral candidate at the Near and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Washington. Her dissertation project, “Constructions of Jewish Modernity and Marginality in Izmir, 1860–1907,” focuses on embodied marginalities and questions how Ottoman Jews constituted their identities within imperi-al and communal settings by focusing on the Jewish poor, diseased, criminal, and convert to Christianity of Izmir. She is currently a doctoral fellow at the Posen Society of Fellows and Stroum Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Washington.

i Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives (Yale University Press, 2013), 27.