Above: Detail from Rachel Rafael Neis. Three Times a Winner, 2018. Mixed media on paper. 9 in. x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist.

In 1909, the Maccabi Jewish Gymnastics Society of Istanbul (Société Juive de Gymnastique, “Maccabi”) organized a gymnastics exhibition at the Teutonia Club, a popular social club in Istanbul. Members of the club performed athletic feats, twisting and contorting their nimble bodies, in front of a religiously diverse audience of Jews and Muslims. Maccabi’s president, Maurice Abramowitz, delivered an impassioned speech at the event, stressing the significance of physical exercise. Sports and gymnastics, he argued, were the most effective means through which Ottoman Jews cultivated strong, healthy bodies and built a modern Ottoman Jewish community.

Jewish Studies scholarship treats Muscular Judaism and the obsession with the Jewish body as an exclusively central European phenomenon.

Did the event and its discursive framing constitute an iteration of “Muscular Judaism”? If the event had taken place in any city in central Europe during the early twentieth century few scholars would hesitate to answer in the affirmative; however, its setting in the Ottoman Empire seems to give pause. Jewish Studies scholarship treats Muscular Judaism and the obsession with the Jewish body as an exclusively central European phenomenon. It identifies Max Nordau, cofounder of the World Zionist Organization, as the creator of the concept of the “muscular Jew.” Nordau’s idea of Muscular Judaism established connections between this new type of Jew, the muscular Jew, who was physically and morally strong, and a prosperous Jewish nation.

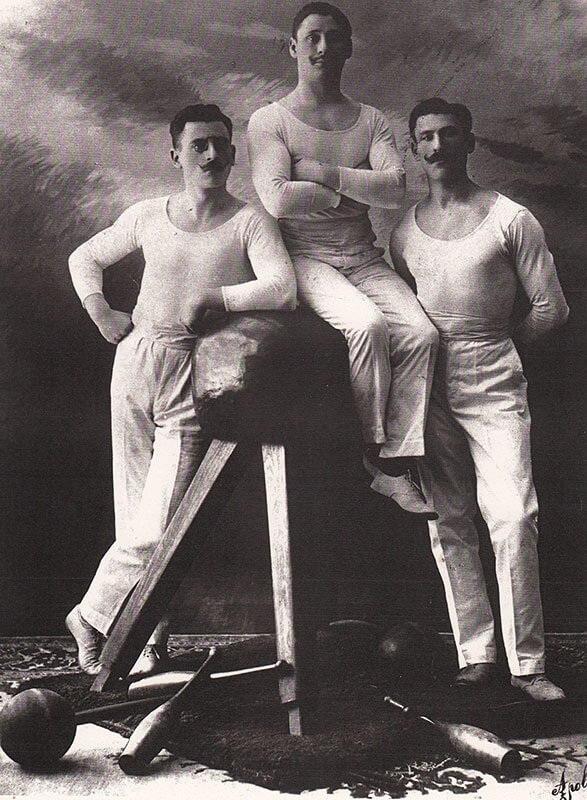

Members of the Jewish Gymnastics Club of Constantinople, 1907.

Left to

right: J. Kornfeld, L. Shoenmass, A. Ziffer. Private archive of Daniel Ziffer.

While Nordau may have coined the term, he did not monopolize it. Moreover, Jewish physical cultural enthusiasts were not confined to writing, organizing, and exercising in central Europe. Jews living in the heart of the Ottoman Empire and at its very edges constructed an inseparable link between strong Jewish bodies and national regeneration. Therefore, I am calling for a more expansive geographical reading of Muscular Judaism.

The activities of Maccabi in Istanbul make abundantly clear that Ottoman Jews focused on the Jewish body as a central site of regeneration. In fact, early twentieth-century German Jewish publications acknowledged this, referring to Maccabi in Istanbul as the oldest Jewish association in the world. Does this mean that Muscular Judaism was not an exclusively European project? What, then, did it look like in the Ottoman Empire and beyond? Can we speak of a Muscular Judaism alla turca?

Muscular Judaism alla turca, or Turkish-style, shares a number of characteristics with Nordau’s reading of Muscular Judaism, which I will refer to as Muscular Judaism alla franga, or European-style. Ottoman and European Jewish educators and intellectuals working both inside and outside of the discourses of Zionism often described Jews as physically weak and degenerate. There were differences, however, in their reading of degeneracy. Contributors to Muscular Judaism alla franga foregrounded the insalubrious state of Jewish streets and yeshiva culture, while Ottoman Jewish educators embraced a more capacious, less clearly defined understanding of Jewish degeneracy. What united them was their belief that Jewish degeneracy was not insurmountable. Self-care and discipline, namely the regular performance of gymnastics and physical exercise, enabled Jews to strengthen their bodies. Once physically and morally strong, these Jewish (male) bodies would serve as the building blocks of a new Jewish community.

There are two significant differences, however. The first difference is the context in which Muscular Judaism alla franga and alla turca emerged. Muscular Judaism alla franga emerged in a context in which there was a “Jewish question.” Ottoman society did not produce a wide-ranging set of debates and discussions exclusively focusing on the status and treatment of Jews, since they were not the empire’s most important or most vexing Other. The second difference relates to Zionism. Practitioners of both iterations of Muscular Judaism were Zionists. However, their Zionism differed. Prior to the First World War, Zionism was polyvalent and geographically diverse. Generally speaking, European Zionism differed from Ottoman Zionism. The political contours of European Zionism were stronger than Ottoman Zionism’s: European Zionists called for Jewish political autonomy, while Ottoman Zionists did not. Notwithstanding these important differences, the lines separating Muscular Judaism alla franga and alla turca were often fluid. This fluidity was connected to space. Istanbul served as a regional hub, attracting foreign-passport holders from Europe as well as Ottomans from all parts of the empire. Therefore, members of the Maccabi Jewish Gymnastics Society of Istanbul encountered the ideas, practices, and institutions that undergirded Muscular Judaism alla franga by reading about them in foreign publications and hearing about them at formal and informal events organized at the club and beyond.

Members of the Maccabi Jewish Gymnastics Society constructed Muscular Judaism alla turca during a time when Istanbul was experiencing a “sports awakening.” This sports awakening consisted of a bustling multilingual sports press, trendy sports clubs, and popular soccer matches and gymnastics exhibitions. Muscular Judaism alla turca was an important contributor to this sports awakening and was also shaped by it. My current book project maps these developments, arguing that Muslims, Jews, Armenians, and Greeks collectively shaped the defining contours of this civic sports culture in Istanbul’s expanding public sphere. It further demonstrates that there were also striking similarities between the ways in which Muslims, Jews, Armenians, and Greeks engaged in sports. Intellectuals, educators, journalists, government officials, and sports enthusiasts fervently asserted that these activities enabled Ottomans from all backgrounds to cultivate robust bodies, modern ethno-religious communities, and a civilized empire. While I continue to tease out the contours of Muscular Judaism alla turca in my work, it is not premature to reflect on the possibilities it offers. Muscular Judaism alla turca serves as a unique lens through which to explore an interconnected history of the Jewish body and physical culture that includes, but is not confined to, central Europe. I focused on Ottoman Istanbul in this article, but it is important to point out that Jewish physical-culture enthusiasts established and joined sports clubs and discussed the necessity of corporeal development in cities across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) during the transition from empire to nation-states. An investigation of the interstices of the Jewish body across the region reveals a layered history that is equally relevant to a number of scholarly fields, namely Jewish, Middle Eastern, and Gender Studies.

This investigation and framing promises to enrich scholarship as well as the courses that we teach. For example, how would lectures on Muscular Judaism in Jewish Studies classes differ if they included an analysis of debates and discussions about the Jewish body and sporting spaces in Baghdad, Berlin, Cairo, and Istanbul, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? What are the implications of including discussions about Muscular Judaism alla franga in courses on gender and the body in the Middle East? In both instances, a more interconnected and multilayered history emerges. Hopefully Jewish, Middle Eastern, and Gender Studies scholars will reflect on these and other questions as they teach the history of Muscular Judaism and the Jewish body.

.tmb-medium.jpg?sfvrsn=d1319606_1)

Murat Yildiz is assistant professor of History at Skidmore College and an assistant editor for the Arab Studies Journal (ASJ), a peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary research publication in the field of Arab and Middle East Studies. He is currently working on a book manuscript that focuses on the making of a shared physical culture among Muslims, Jews, and Christians of late Ottoman Istanbul.