Photos courtesy of the authors.

PEDAGOGY

The analog role-playing game Rosenstrasse asks players to take on the roles of characters struggling to survive under the Third Reich. Over the course of four hours, players explore marriages between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans in Berlin between 1933 and 1943, and play out the pressures that both partners experienced. The game culminates in the women-led 1943 protest, known as Rosenstrasse after the square in which the women demonstrated, that resulted in the release of nearly 1,500 Jewish men.

The Rosenstrasse game materials. Clockwise from top right: character cards, the facilitator’s guidebook, the risk matrix, and scenario cards. Not shown: star tokens and postcards.

As a role-playing game, the core activity of Rosenstrasse is players speaking and acting as their characters. Eight pregenerated characters come with the game: male and female, Jewish and non-Jewish, relatively secure and entirely vulnerable. At the beginning of the game, each player is assigned two characters that they are to portray for the rest of the session. It is through these characters that players investigate the historical events of the period.

As an analog game, Rosenstrasse asks players to gather in person around a table. Four players and one facilitator spend four hours together, speaking and listening and looking at one another. Because players are gathered in person to play, they can see what other players do, which lets them compare and contrast the experiences of different characters. By embodying their own characters while others watch, they also develop a deep connection to the characters that they themselves portray.

As a transformational game, Rosenstrasse seeks to change players through the experience of play. The game has three goals: to educate players about a lesser-known historical moment; to inspire them to resist oppression in their daily lives; and to help them start conversations about activism. Our research on the game to date suggests that the game is indeed powerfully transformational. After playing Rosenstrasse, players report attending protests, starting conversations with family members about the Holocaust, and even traveling to Berlin to visit the Rosenstrasse memorial. In other words, the game helps players translate abstract knowledge into embodied action.

A sample scenario card from Rosenstrasse. This scene between secular intellectual spouses Josef (Jewish) and Klara (not Jewish) takes place early in the game and is discussed below. Their decision about whether to baptize their children will have long-term implications for the safety of the entire family.

Many role-playing games are open-ended. Rosenstrasse, however, uses card-based scenarios to structure the scenes that players encounter. Each card contains a brief description of a situation, then ends with a prompt for players to respond to. This design decision is thematically appropriate; players should not be able to change the behavior of the Reich. Giving players the power to affect the core narrative arc of the game would not just be inaccurate, but disrespectful to the victims and survivors of the Nazi regime.

Each card has a number on the back, indicating the order in which they are to be drawn from the deck. While some cards are discarded based on players’ choices, most cards remain the same from game to game. Players are offered the same scenarios in the same order. Their creative contribution to the game is in how they react to the prompts for each scenario.

Consider a scenario in which Klara and Josef, one of the couples in the game, must decide whether to baptize their children. Some aspects of the situation are constant. Josef is always Jewish, and Klara is always non-Jewish; both are committed secular humanists. They are always married and have two children. Klara always realizes that baptizing their children may make them all safer, and always sits Josef down to have a conversation about it—but other things are different every time. For example, across games, players take different positions on the issue. Some Klaras are looking to be reassured that a baptism isn’t really necessary; others are willing to fight their corner to the bitter end. Some Josefs discover that the notion of a baptism revolts their Jewish soul, while others object on humanist grounds, and still others find that they don’t mind as long as they don’t have to attend. These positions are played out in the dialogue the players speak as their characters; in the internal experiences they have, which they typically share after the game; and, of course, in the ways they use their bodies.

The woman in the blue shirt slams her hand down on the table. “Klara,” she says, adopting the voice she’s been using for Josef, “I can’t bear this. To baptize our children— just to make them safe! I won’t do it. I won’t.”

Unlike most role-playing games, in which each player has a single character, in Rosenstrasse players are assigned two characters: one male, one female. Each scenario card is directed to specific characters, who are listed on the back of the card. In a given scenario, a player might be taking on the role of either their male character or their female character. In other words, regardless of the player’s gender, they are playing a character of a different gender at least part of the time. The game contains no directives for how players should distinguish their two characters, or how players should portray their character’s gender. These decisions are left for players to explore.

During play, players find spontaneous solutions to distinguish their two characters. For example, some players change their voices, some stand differently, and some move around the table depending on who they are portraying. The game provides character cards for each character, which means each player has two character cards in front of them; some players stack them so that only the character they are currently portraying is visible. Finally, some players use objects that happen to be nearby in their gender performance. For example, a scarf pulled from someone’s bag might be wrapped around the head to indicate that the female character is being portrayed, while wrapping it like a cravat indicates masculinity.

The gray-haired man’s shoulders slump. “Klara,” he says, “How can we do this to our children? With everything we believe? With—with everything I believe?” He isn’t a Jew, but right now his body is a Jewish one.

In modern society, the Jewish body is not only gendered, but stereotyped in gendered ways. For example, Jewish men are stereotypically weak, while Jewish women’s bodies are often portrayed as untamable. As with gender, Rosenstrasse resists these stereotypes by asking all players to embody Jewish characters. Every player receives at least one Jewish character during play—even if the character doesn’t know it when they begin the game.

To avoid stereotypes, the characters’ relationships with Jewishness vary. For siblings Ruth and Izak, and for newlywed musician Max, Judaism is joyfully tied to family, heritage, and tradition. For Josef, it is an outdated tradition to be challenged by a commitment to pure reason. For Kurt and Klara, it’s a dangerous secret that could get them killed. For Inge and Annaliese, Jewishness is central to their relationship with childbearing and child-rearing, which focuses it on the body. In other words, whether players are Jewish or not, the game asks them to speak with a Jewish mouth, gesture with Jewish hands, and see the world with Jewish eyes.

The blue-haired person and the short woman stand together, looking each other in the eyes. As Klara and Josef, they have just gone through a stormy argument. Now they breathe together, calming. “Do you trust me?” the woman murmurs. “I do,” says her partner, and takes her hand.

Some scenes are directed to just one character. In these scenes, the player describes their character’s interaction with the game world, or with nonplayer characters portrayed by the facilitator. However, most scenes in the deck are directed to two characters: a husband and wife, or two siblings. Each character is portrayed by a different player, so that the two players connect just as their two characters do.

The facilitator is offered two techniques to build the embodied connection between the players. If the players are primarily seated during play, then the facilitator can hand them the card from the deck without reading it. Because the text on the card is relatively small, but both players need to reference it, they lean their bodies together to see more clearly. This small, typically unconscious gesture builds a sense of connection between the players, which gives weight to the marital or familial relationship of the characters. Alternately, if players have shown a willingness to stand and move while portraying their characters, the facilitator can ask them to first stand, then to listen while reading the card. As the facilitator reads, the players can decide how far apart their characters should stand, and begin expressing their attitudes about the scene through body language.

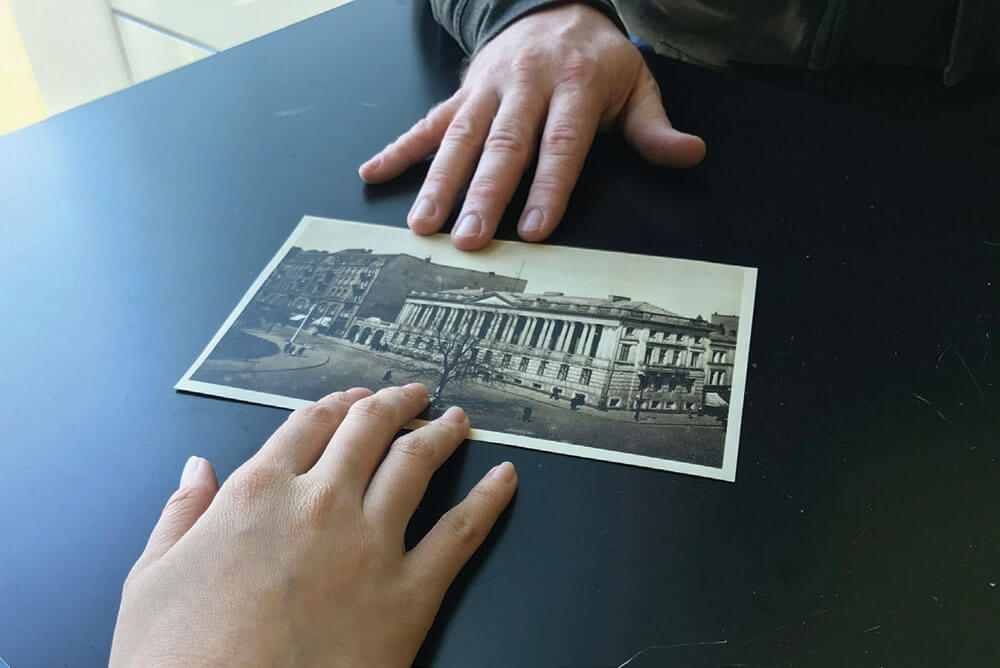

The facilitator passing a postcard to one of the players. Some players have the opportunity to write a postcard, in character as their male character, to their loved ones at the end of the game.

Rosenstrasse is an intense emotional experience. It is not “fun” in the traditional sense of the word. However, in playtests with over two hundred players, and a qualitative research study with eighteen subjects, we have found that players find it deeply meaningful. From Holocaust educators and from people who had previously believed the Holocaust was a hoax, from expert role-players and from novice gamers, from the descendants of survivors and the descendants of perpetrators, we have heard over and over again that players are moved, shaken, inspired.

This is deliberate. Rosenstrasse is an explicitly transformational game, one that seeks to change players through the play experience. Part of how Rosenstrasse accomplishes its goals is through the body. It is deliberate that the game is played at a table, not in front of a screen; that players must pick up cards and read them aloud; that players must speak and act as their characters, not type text describing what they do.

Theories of embodied cognition inform the physical materials of the game. By offloading historical knowledge into the cards that players handle, they can focus their cognitive resources on portraying how their characters would react to the history being described. The physical materials also track the state of the game. Players do not have to remember that the game is moving toward horror and death. As the card deck becomes depleted, players have an immediate visual reminder of how much time is left before the end of the game—and before they must discover their characters’ fates. The deck becomes the ticking clock, and the players’ hands are the tick tick tick of time moving it forward.

Our findings show that Rosenstrasse is a transformational and highly effective experience. For example, after playing, many players say they now understand why Jews did not simply “just leave” Germany. Other players cite the game as a spur to activism on behalf of the oppressed, even months after play. Almost every group conducted spontaneous historical research after the game ended, and multiple players reported visiting the Rosenstrasse memorial in Berlin because of their experience in the game. We believe that part of what makes this transformation possible is the physicality of the game—that players never have to transfer knowledge from their mind to their bodies, because they are learning it with their bodies as well as their minds in the first place.

What other Jewish stories might be told through these types of role-playing experiences? We hope to find out.

Rosenstrasse was created by Jessica Hammer and Moyra Turkington as part of the War Birds project, which are games that center the experiences of women in wartime. Rosenstrasse successfully Kickstarted in spring 2019 and will be released later this year. More information about Rosenstrasse and other games in the War Birds series is available on the Unruly Designs website.

JESSICA HAMMER is the Thomas and Lydia Moran Assistant Professor of Learning Science at Carnegie Mellon University. Her research focuses on how games can transform the way players think, feel, and behave. She received Carnegie Mellon University's Teaching Innovation Award in 2018, and she is also an award-winning game designer.

MOYRA TURKINGTON is the founder of the indie studio Unruly Designs and the leader of the War Birds collective—an international team of designers writing chamber games about women fighting on the front lines of history. She is interested in personal, political, transformative games that challenge how we understand the world and each other. A systems analyst with a joint background in Theatre and Cultural Studies, she is always working to develop multiplicity and access in media, design, representation, and play.