Above: Detail from Rachel Rafael Neis. Bestial Beach Party II, 2019. Acrylic on canvas. 32 in. x 38 in. Courtesy of the artist.

THE PROFESSION

Ada Lieb’s physical and mental disabilities almost forced her to leave the United States. Her family migrated from Russia to Nashville in 1922, where Ada found employment as a milliner thanks to her talent for needlework. Upon developing anxiety, numbness in one leg, and tremors in one hand resulting from childhood trauma, she transitioned to retail—until her employer fired her because of her shyness and limited English. Joblessness triggered “a sort of melancholia,” in which Ada stopped speaking and refused food. After a doctor insisted that Ada’s “physical disability was only a child of her mind,” she nearly found herself an inmate of a public mental institution. Fortuitously, a caseworker from the National Council of Jewish Women intervened. Emphasizing that admitting Ada to this asylum would classify her as a “public charge” and instigate her deportation,i this caseworker pressed for Ada’s return to her former position and access to a swimming pool to manage her disabilities. Through providing Ada with the necessary accommodations, this caseworker enabled her to remain and thrive in the United States.ii

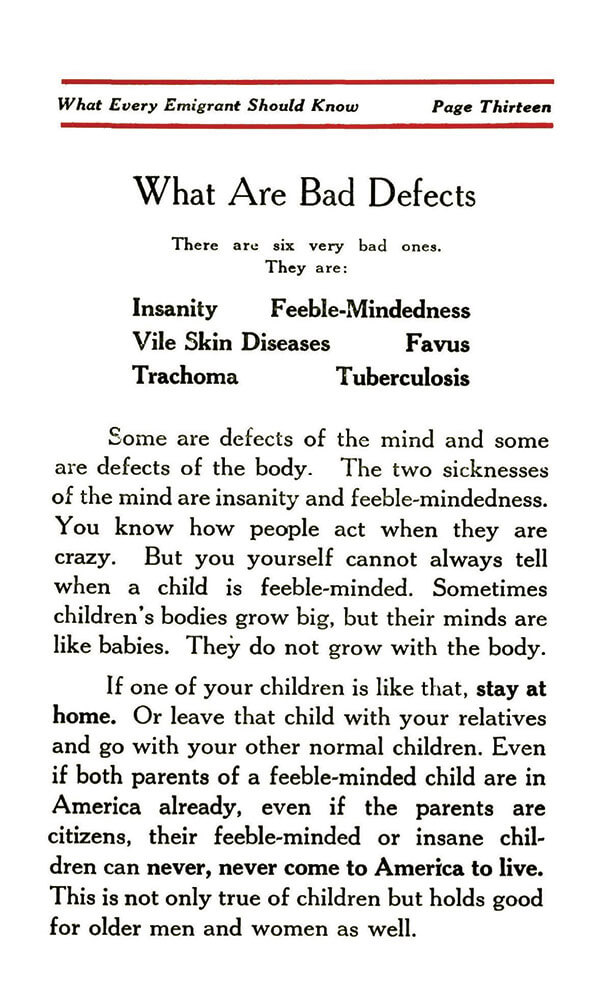

“What Are Bad Defects” from Cecilia Razovsky’s pamphlet, What Every Emigrant Should Know (Council of Jewish Women, 1922), 13.

Ada’s story ended more happily than many others. The 1917 Immigration Act expanded the categories of “undesirable” immigrants to include “idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded persons, epileptics, insane, persons of psychopathic constitutional inferiority, persons afflicted with a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease, including venereal disease, trachoma and certain chronic conditions.” Stemming from the 1882 public charge provision, the 1917 law targeted “mental and physical defectives” for debarment and broadened the terms mandating their deportation.

Immigration and deportation policy expose overarching attitudes towards disabled and ill bodies, revealing “what kind of people may come to America, and what kind of people must stay at home.”iii Wide-ranging conditions could provoke debarment. In 1909 and 1910, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society documented that heart disease, “lack of physical development,” and hernias recurred as grounds warranting exclusion and deportation. Public charge remains in force today, deploying health and disability to prohibit immigrants from entering the United States. Last fall, the Trump administration issued a proposed rule to permit the deportation of “foreign-born noncitizens” as public charges, based on their use of public benefits such as Medicaid and Medicare.

Acknowledging ingrained assumptions about people with disabilities and illnesses illuminates their marginalization, both in terms of physical exclusion and narrative omission. Implicit expectations of “normative” health and ability shape our research and construction of academic spaces. Having lived with chronic illnesses since childhood, I am inclined to notice systems and structures designed in ways that overlook “aberrant” bodies and minds.

The centrality of academic conferences to career advancement constitutes a salient example. Traveling to conferences poses a challenge for our colleagues with illnesses and disabilities, who frequently struggle to meet fundamental health needs in their own environments, let alone new ones in which they must present at their best under unfamiliar conditions. Allocated funding to defray expenses for critical medical and dietary accommodations, and embracing technology enabling remote participation (like Virtually Connecting, Zoom, and Skype), would allow those with health conditions to attend conferences on an equal level with their nondisabled peers.

Fostering inclusive conferences and classrooms requires that we utilize disability as a standard analytical lens alongside gender, race, ethnicity, and class. To start, we can treat disability as worthy of study by encouraging projects explicitly addressing its presence or absence as foundational to interaction with and perception of the world. As such, we can cultivate a sociointellectual environment that values the contributions and experiences of people with illnesses and disabilities as scholars and historical subjects. The AJS could signify a commitment to physical and mental diversity in our discipline by adding a Disability Studies division to its annual conference, promoting inclusive scholarship that will offer invaluable dimensions to the field. Feminist scholars reminded us in the 1970s that representation matters. We today can take their advocacy for Women’s and Gender Studies as a model for incorporating disability—which similarly informs everyday existence—into academic inquiry. Considering health and disability proffers an invaluable opportunity for Jewish Studies scholars to push the boundaries of the field, reevaluating whose voices we center, approaching archives anew, and reexamining conventional language and narratives. Restoring stories like Ada’s to the historical record provides an excellent place to begin.

HANNAH GREENE is a doctoral candidate at New York University’s Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, where she studies American Jewish history. Her dissertation addresses American Jews’ organized political, legislative, and social engagement with United States immigration and deportation policy and its enforcement, particularly the public charge provision and related issues of health and disability. Her chapter “‘Please Have That as a Personal Matter’: Lillian Wald and Birth Control in the United States” is forthcoming in the edited volume Sexing Jewish History: Jewishness and Sexuality in the 19th and 20th Century United States.

i Mrs. J. Weinstein to Cecilia Razovsky, Box 1, Folder 1, Cecilia Razovsky Papers, 1913–1971, American Jewish Historical Society, Center for Jewish History.

ii Cecilia Razovsky, What Every Emigrant Should Know (Council of Jewish Women, 1922).

iii HIAS records of deportation, 1909–1910, Box 11, Folder 12, Max James Kohler papers, 1765–1963, American Jewish Historical Society, Center for Jewish History.