Above: R.B. Kitaj. Eclipse of God (After the Uccello Panel Called Breaking Down the Jew's Door), 1997-2000. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35 15/16 in. x 47 15/16 in. Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Memorial and S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Funds, 2000-71. Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. Photo Credit: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY. © 2020 R.B. Kitaj Estate

RESPONDING TO HATE

“How pure is your hate?” This is the question my colleague asks their students on the first day of class, echoing the late Alexander Cockburn. My colleague asks this question with a desire for unwavering passion—including unwavering hate—on issues concerning capitalism, climate change, and racial injustice. They hope students will share in their disdain for inequality—whether against humans or against lands—and therefore find value in the qualification of their opening question. “How pure is your hate [for injustice]?” really, is the question they aim to ask.

And yet.

As both an academic and a queer Jewish American, the word that stands out for me in the question is not so much “hate,” but rather “pure.” What, in other words, does “purity” mean? What does “pure hate” mean? How might conceptions of purity contribute to conceptions of hate?

My focus here will be on conceptions of purity in relation to Jewishness and queerness, beginning with the former and then putting it in conversation with the latter.

“Jew,” historically, isn’t the most likable term. As Religious Studies professor Cynthia Baker explains, “For most of two long millennia, the word Jew has been predominantly defined and delimited as a term for not-self.”i To be a Jew, put simply, is to be culturally, ethnically, theologically, and even racially Other to the Self that is Western Christianity.

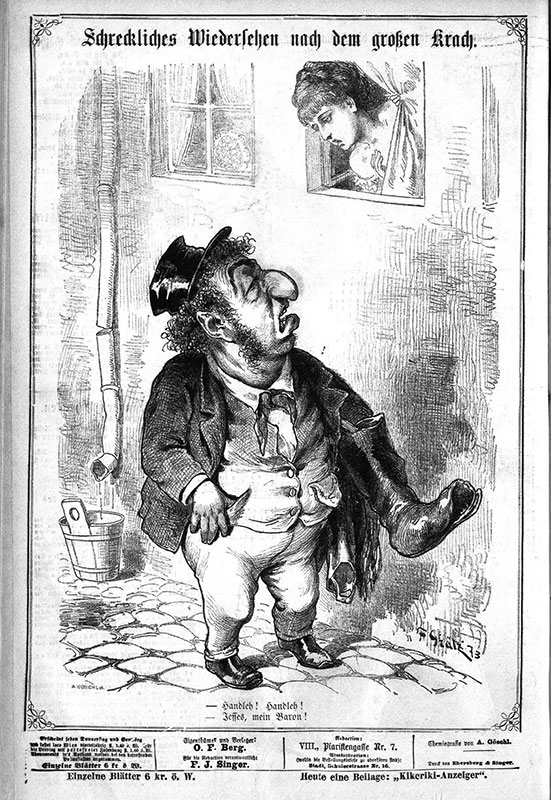

Cartoon printed in the May 18, 1873 edition of Kikeriki. ANNO, Austrian National Library.

The race of the Jew is particularly unstable. As a social construct, all conceptions of race are unstable (we could divide humans by thousands of characteristics, including height, hearing capacities, allergies, etc.), but Jews have become quintessential examples of race as construct. According to the “race science” of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, for instance, Jews are biologically not white; physiognomic features such as the big nose, big lips, and big hair proved their non-whiteness even outside of skin pigmentation. Such rendering today, however, does not hold. Jews of eastern European descent, regardless of antisemitic renderings of nose, mouth, and hair, are considered white. They, moreover, at least according to political activist Houria Bouteldja, opt into such whiteness. The Jew is recognizable, she asserts, “not because he [sic] calls himself one, but because of his willingness to meld into whiteness.”ii

Holding this here, let me transition to queerness—or, more precisely, a story about my own queerness, which will then take me back to Jewishness.

The day before I turned thirty-two, I was walking in the East Village of New York City holding hands with my girlfriend. We were two curly-haired, Ashkenazic Jews celebrating my birthday in our favorite city (and in a neighborhood I like to call, perhaps just after Disney World, the “Gayest Place On Earth”).

… he did this while staring back at me with what I can only describe as pure hate. His derision was unwavering.

Maybe the man assumed we were just good friends; self-identifying women, after all, are often thought to show affection in friendship more quickly than self-identifying men due to various social norms and privileges.

Maybe, moreover, he was angry at our privilege— the fact that we were two white women walking down the street, never having to face systemic discrimination.

Or maybe he could tell we were Jews. We have the physiognomic curly hair. I have the physiognomic long nose. And there we were, benefitting from the Jew’s new whiteness, indeed melding into such whiteness, as we walked toward a hotel bar.

This is where the conversation concerning queerness, Jewishness, and purity intersect. Jews, on the one hand, are of a not-place. Their identity shifts based on who is doing the talking. Even while benefitting from the privileges of white presentation, they are not “purely” white, they are molding. White supremacists and antisemites have noted that the Jews’ lack of “purity” here is what makes them so dangerous; some Jews can pass as white, but they really aren’t.

That does not mean, however, that “white-appearing” Jews necessarily claim a particular not-white status. In the words of Cheryl Greenberg, “Emotionally, historically, in the ways that are most relevant in the shaping of identity, Jews have never considered themselves white. Nor do they consider themselves Black, or a subset of any other racial group.”iii In a sense, we might even say that the antisemites are right. Jews do not belong anywhere. They are the epitome of the Not-Self—the epitome of the Not Pure.

Let me be clear when I say that I have no idea what the man’s intentions were when he kicked me. In all likelihood, it was homophobia. Interestingly, though, his homophobic actions did not ignite externalized hate or even internalized queer-hate, but rather another sort of self-hate: internalized anti-Jewishness.

Why? I have a few theories. One in particular is that queerness celebrates the impure; it celebrates disruption, destabilization, and the space between the binary. I feel protected by fellow queers and queer allies in that celebration. But the impurities of Jewishness? No. I do not feel protected. And what is more? My internalized anti-Jewishness tells me that the lack of protection is deserved. Jews are part of the problem. To quote Bouteldja once more, the Jew is recognizable, “because of his willingness to meld into whiteness.” My impurity, which is my malleability, is a problem on all sides.

But maybe we can turn this around. Maybe my Jewishness and my queerness are indeed two sides of the same coin. Queerness, after all, celebrates the unstable. It celebrates the power of disruption and malleability. Maybe, then, to be Jewish is to also be queer, at least in some form or another. If Jewish identity has taught me anything, it is that identity is messy and understandings of the world are multiple. Two Jews, three opinions? No problem.

So, how pure is my hate? I don’t know. But what I do know is this: I’d rather dismantle systemic injustices— including those targeted within—queerly than purely.

SARAH EMANUEL is visiting assistant professor of Biblical Studies at Colby College. Her most recent publications include Humor, Resistance, and Jewish Cultural Persistence on the Book of Revelation: Roasting Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2020); “Letting Judges Breathe: Queer Survivance in the Book of Judges and Gad Beck’s An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin” in the Journal for the Study of the Old Testament; and “On the Eighth Day, God Laughed: ‘Jewing’ Humor and Self-Deprecation in the Gospel of Mark and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend” in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies.

i Emphasis original. Cynthia M. Baker, Jew (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 4.

ii Houria Bouteldja, Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love, trans. Rachel Valinsky (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2017), 54.

iii Cheryl Greenberg, “‘I’m Not White--I’m Jewish’: The Racial Politics of American Jews,” in Race, Color, Identity: Rethinking Discourses about “Jews” in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Efraim Sicher (New York: Berghahn, 2013), 46.