Above: R.B. Kitaj. Eclipse of God (After the Uccello Panel Called Breaking Down the Jew's Door), 1997-2000. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35 15/16 in. x 47 15/16 in. Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Memorial and S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Funds, 2000-71. Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. Photo Credit: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY. © 2020 R.B. Kitaj Estate

Who said it? Wasn’t it Elijah the Prophet?

... Or perhaps it was Joseph the Demon?

—Babylonian Talmud Eruvin 43a

Demonization has become such a powerful feature of public discourse that few of us escape its allure. The current “discourse of demonization” includes direct demonization (constructing Others as thoroughly, perhaps irredeemably, alien and evil); counterdemonization (delegitimizing Others’ claims by accusing them of demonization); and self-demonization (seeking discursive power by brazenly defying conventional norms). Who does not indulge in at least one, if not more, of these? Don’t we all perceive at least some of our political, religious, or cultural adversaries to be situated on the “other side” of a moral chasm? Can we, without bad faith, or betrayal of our moral values, preach the acceptance of the Other who seeks to destroy those values? Might demonization, to borrow Sartre’s phrase, be the “untranscendable horizon of our time”?

The multifaceted discourse of demonization also implicates key questions in recent academic debates. Counterdemonizers, for example, often indict others for improper transgressions of the religion/secularity divide. They charge them with importing religious, even superstitious, images of absolute evil into discussions that should be conducted in the rational spirit of pragmatic compromise. This form of counterdemonization is quite widespread in the academy and beyond it. Yet, for more than a generation, critical thinkers have highlighted the contingent and contestable contours of the very religion/ secularity dichotomy that is its fulcrum.

Moreover, attacks on “demonizers” cannot be neatly characterized as advancing secular reason over religious irrationality. Rather, one key genealogy of such attacks lies in intrareligious polemics—ranging from the Church Fathers’ rejection of gnostic dualism to Maimonides’s rejection of rabbinic demonology. Conversely, placing certain positions beyond the pale has a long history in putatively secular political discourse—from violent fascist exclusions to the genteel strictures of Habermasian protocols.

Longstanding Jewish discourses about the demonic Other, both rabbinic and kabbalistic, provide a nuanced optic on our era. Rabbinic demons were, by turns, friendly and hostile, helpful and destructive: “like human beings” in three ways and “like ministering angels” in three ways (Talmud Hagigah). Such demons can neither be domesticated nor shunned—and, at times, can barely be distinguished from their holy counterparts. Ashmedai, King of the Demons, was indispensable for the building of the Temple; he also subsequently usurped Solomon’s throne and slept with his wives. The ease with which those wives mistook Ashmedai for Solomon suggests that he was something of Solomon’s twin—and, indeed, according to one midrash, he was Solomon’s half-brother.

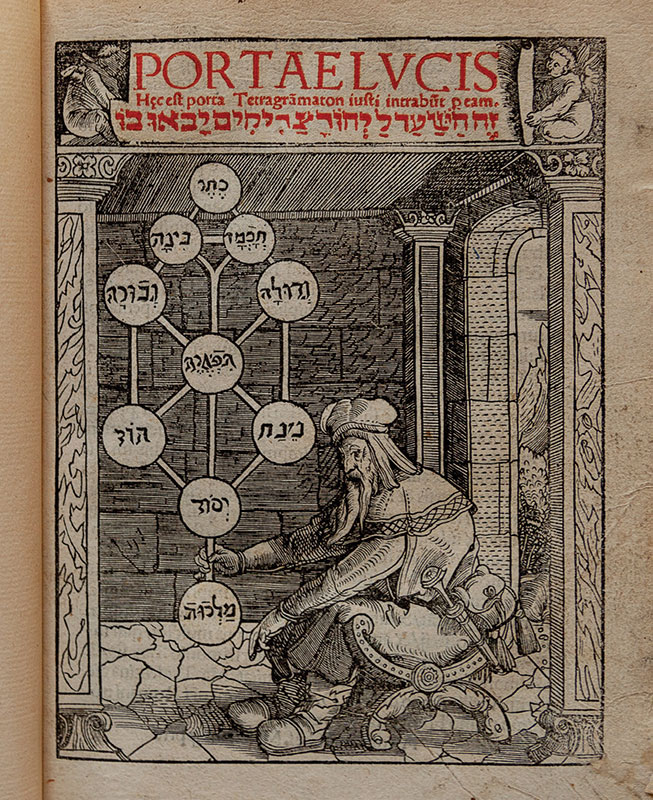

Abraham Joseph Gikatilla. Portae Lucis. (Augsburg: Johann Miller, 1516): title page. Photo by Sander Petrus, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Such twinning comes to the fore in kabbalistic texts— where it takes the more fraught form of divine/demonic relationships. Such dangers include the ultimate misprision: worshiping a demonic entity instead of the divine entity it resembles. Zoharic and later kabbalistic texts evoke a human condition of urgent uncertainty, an existentialism avant la lettre, in which choice is both groundless and yet unavoidable.

Kabbalistic portrayals of the ultimate source of such misprisions heighten their fraught intractability. Some Zoharic texts allude to demonic personae as immature or fallen forms of divine personae:i the diabolical “Edom” as an immature form of the supreme divine persona, the Holy Ancient One (Liebes),ii the diabolical Esau/Sama’el as the fallen form (and twin) of the divine Jacob/Blessed Holy One (Wolfson).iii Other texts paint deep affinities between the diabolical Lilith and the divine Shekhinah. These two personae at times emerge from each other, at times metamorphize into each other, at times seem almost indistinguishable. Still other texts portray diabolical personae arising from the dissociation of a divine persona: a phenomenon of particular relevance to our time, the “age of anger” (Mishra).iv

The skill of Zoharic writing lies in its paradoxical evocation of both the deep affinity between the Hated and the Beloved, and the duty of passionate engagement in the mortal struggle between them.

Anger is, indeed, a key Zoharic path by which a divine persona becomes, or gives rise to, a diabolical persona. One text portrays the fire of divine anger emitting smoke, which curls around until it takes form as Sama’el and Lilith— who are thus literally the crystallizations of divine wrath. Another text portrays a similar process on the human level. Kabbalistic ambivalence reaches its peak in Zoharic portrayals of the diabolical Dragon as another face of the loving God, the hated Enemy as another face of the cherished Friend. The skill of Zoharic writing lies in its paradoxical evocation of both the deep affinity between the Hated and the Beloved, and the duty of passionate engagement in the mortal struggle between them.

This insistent portrayal of the divine/demonic relationship as marked by absolute enmity and deep affinity makes sense of the fact that Zoharic and other kabbalistic texts forecast opposite ultimate fates for the demonic: reconciliation, even embrace, with the divine and utter annihilation by the divine. Similarly divergent counsel may be found in kabbalistic ethical texts as to how one should relate to sinners: embrace and ostracism. It thus also makes sense that in recent decades Kabbalah has inspired forms of Judaism most embracing of ideas, rituals, and even deities of other traditions, as well as intolerant, nationalist, and even racist forms of Judaism.

The ultimate edifying lesson of this brief overview of the kabbalistic demonic may not lie in the stark choice it portrays between embrace and annihilation of the Other. Rather, it lies in the writing, especially Zoharic writing, which makes that choice visible: a writing neither so deeply embedded in the divided world that it cannot see beyond it, nor so self-deluded as to pretend to be above that world and its struggles. The former would render it ignorant of the deep affinities between Self and Other, Friend and Enemy; the latter would render it incapable not only of acknowledging its own hostile emotions towards an immoral adversary, but, more importantly, of maintaining the passion of its own commitments. “Self-aware situatedness” might be a slogan for this simultaneously tragic and utopian vision.

We live an age of demonization, yes, and we cannot simply will ourselves beyond it. But kabbalistic myths— perhaps in contemporary revisionist forms—can enable us to nourish still-inchoate hopes of a healing beyond today’s divisions, even while affirming our moral clarity in opposing evil.

NATHANIEL BERMAN holds the Rahel Varnhagen Chair in Brown University’s Department of Religious Studies. Among his publications are Divine and Demonic in the Poetic Mythology of The Zohar: The “Other Side” of Kabbalah (The Hague: Brill 2018) and Passion and Ambivalence: Colonialism, Nationalism, and International Law (The Hague: Brill, 2011).

i My designation of these figures as personae follows the practice of scholars such as Elliot Wolfson, Language, Eros, Being: Kabbalistic Hermeneutics and Poetic Imagination (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), 183, and Yonatan Bennaroch, “God and His Son: Christian Affinities in the Shaping of the Sava and Yanuka Figures in the Zohar,” Jewish Quarterly Review, 107 (2017), 48. The Zoharic literature, curiously, does not employ any general term to refer to them. Later kabbalistic texts pervasively designate them with the term partsufim, a rabbinic Aramaic word for “faces” or “facial features.” Partsuf is itself a loan word from Greek, deriving from prosopon, whose original meaning was “mask” or “face.” Persona is the Latin equivalent of prosopon.

ii Yehuda Liebes, “Ha-Mythos Ha-Kabbali be-fi Orpheus,” p. 30.

iii Elliot Wolfson, “Light through Darkness: The Ideal of Human Perfection in the Zohar,” Harvard Theological Review, 81 (1988), 81 n. 9.

iv Pankaj Mashri, Age of Anger: A History of the Present (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017).