Above: Detail from Siona Benjamin. Finding Home #75 (Fereshteh) “Lilith,” 2005. 30 x 26 in. Gouache on wood panel. © 2005 Siona Benjamin. Courtesy of the artist.

Eugenia Bekeris remembers the bombing very clearly, even decades later, turning to vivid details of the moment of disruption in 1994 when the main Jewish community in Argentina was destroyed: “When the attack happened, no matter where you were, you could hear the bombing. I ... could hear the glass [and walls] shake.” She could not believe what happened at first, and then ran to buy supplies to take to the site of the building, now in ruins, trying to help in whatever way she could.

On that day, Monday, July 18th, 1994, a truck bomb destroyed the AMIA (the Argentine Jewish Mutual Aid Society), killing eighty-five people and wounding hundreds. The community center was destroyed, along with Yiddish-language community archives. Considered one of the worst cases of antisemitic violence in the Western Hemisphere, the attack fractured a sense of belonging for Jewish Argentines. In response, they tried to find a way forward, rebuilding community practices and demanding justice from the state through protests that folded Jewish practice into Argentine civil society. These cultural practices were based in remembering the victims to resist their disappearance from the public consciousness, all with the hopes of finding answers.

Over many years, the Monday morning protests were a way to build a shared fabric of remembering, a collective form of public testimony to stand in for the justice they hoped would come.

Years later, questions remain: Who did it? Why? Will they ever be held accountable? There have been allegations made against Hezbollah and Iran, but they have denied responsibility. Many Argentines are also concerned with the role of state agents in relation to the bombing and the botched investigation that further frayed any chance for establishing the truth of what happened. Despite two trials and local and international advocacy, no one has taken responsibility for this attack, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights declared that Argentina has failed to provide justice in this case. What does it mean, then, for citizens to continue fighting for justice after decades of impunity? And what might new forms of witnessing tell us about sustaining Jewish belonging?

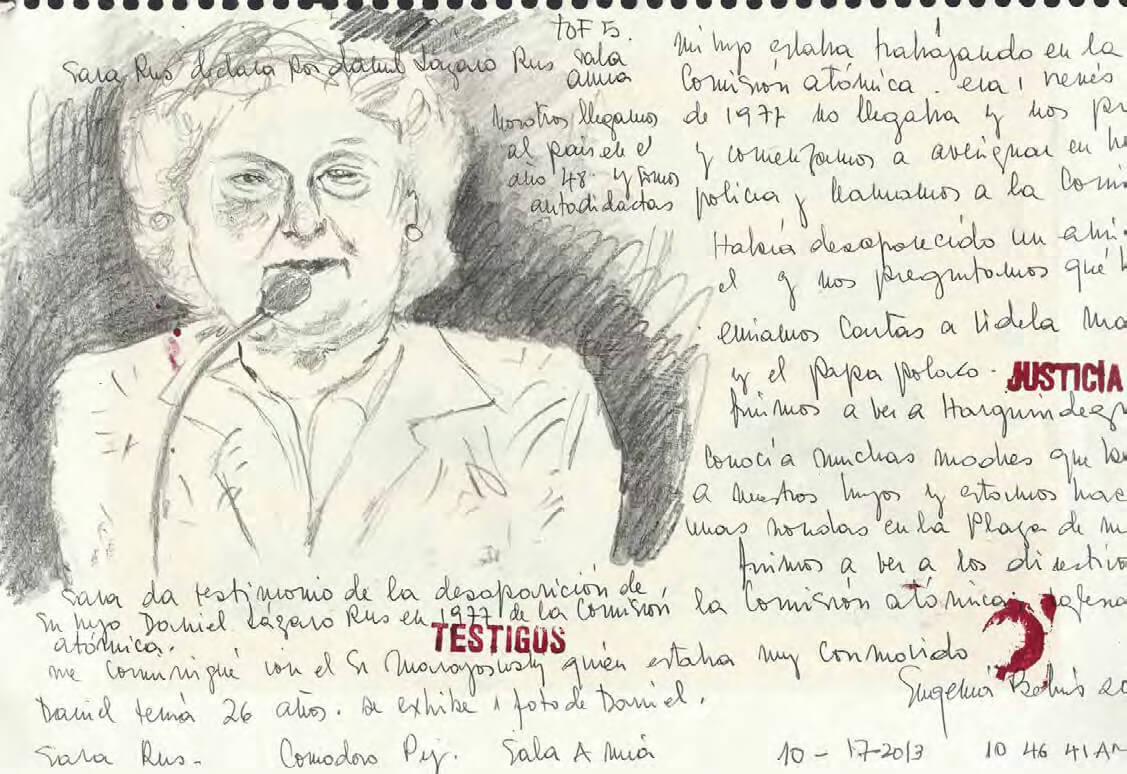

Eugenia Bekeris. Sara Rus at the ESMA megatrial, 2013. Drawing for Dibujos Urgentes. Courtesy of the artist.

For years after the attack, Monday mornings were devoted to standing in front of the high courts in protests organized by the group Memoria Activa. Every week, at the day and time of the attacks, they would blow the shofar to remember the victims, and invoking Deuteronomy 16:8, to shout ẓedek, ẓedek tirdof, justice, justice, you shall pursue. For them, the pursuit of justice was a profoundly Jewish and Argentine act, as such public protests also aligned with how other human rights groups, like the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, challenged the state on the impunity related to the 1976–1983 dictatorship. Over many years, the Monday morning protests were a way to build a shared fabric of remembering, a collective form of public testimony to stand in for the justice they hoped would come. And despite the inadequacy of the trials that have taken place, they did open up new forms of witnessing, which have been just as important to the process of survival for Jewish Argentines.

It was in the audience of the most recent AMIA trial where I met Eugenia in 2018, who was there as an artist to chronicle the trial. Eugenia’s earlier project, El Secreto (The Secret, 1995), “was meant,” she said, “as an homage to her family who had died in the Shoah, but in reality, it became [a way to remember] the AMIA and also, the disappeared,” here referring to the estimated 30,000 victims of the 1976–1983 dictatorship, many of whom were Jewish.

This work later led her to join the artists’ collective Dibujos Urgentes (Urgent Drawings), which visually chronicles the proceedings of human rights trials, a new form of witnessing prompted by a call from the group HIJOS, children of those disappeared during the dictatorship. Cameras had been banned in many human rights trials after the 2006 disappearance of Julio López, who had been tortured during the dictatorship and then disappeared again when he was supposed to testify in the trial of Miguel Etchecolatz, one of the perpetrators accused of crimes against humanity.

Since photography was not allowed in these trials, Eugenia and a team of other illustrators (including María Paula Doberti) used ordinary notebooks and pencils to register visual details that may not otherwise appear in the trial transcripts—the expressions on a face, the moments of humanity and vulnerability. (They recently published their artwork in a book.)

Eugenia found the task challenging. While she had worked with Holocaust survivors before, she struggled with her first drawing at a trial, where she illustrated a woman giving her testimony about her friend who was a victim of the death flights of the disappeared, whose bodies were thrown from planes into the River Plate. The drawing included with this article depicts Sara Rus, a Holocaust survivor who lived through the war in the Lodz Ghetto and later in the Auschwitz–Birkenau and Mauthausen concentration camps. She migrated to Argentina in 1948, and her son Daniel Lázaro Rus was disappeared during the dictatorship in 1977. She is a member of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, Founding Line.

Eugenia told me she went there “with [her] heart in her hands,” adding, “the drawings are called ‘urgent’ and they have an aesthetic quality that we respect—they are done rapidly, and we do not touch them afterwards … we take fragments from the testimonies and we are trying to trap this image from the trials, so it has to be quick.” Trapping this image means holding on to that which would otherwise dissolve, perhaps, into that moment, into time itself.

As one of the witnesses she illustrated told her, “We are not interested in the drawings. What matters to us is that you are there.”

Yet, she also learned what was most important. As one of the witnesses she illustrated told her, “We are not interested in the drawings. What matters to us is that you are there.”

Although originally conceived as a way to chronicle the human rights trials related to the dictatorship, Dibujos Urgentes extended this form of witnessing to the 2015–2019 AMIA trial, which was taking place in the same court building. In this way, they also helped expand the framing of the AMIA case as a question of the impunity that affects all Argentines. In this way, it also implicated them as citizens and invited new forms of witnessing—whether it is protesting in the streets or sitting in the courtrooms, as Eugenia does, to urgently draw and visually register the testimony, opening the space of witnessing to those who cannot be present there through the act of viewing these illustrations.

In thinking about the call from their years of protests in front of the high courts—ẓedek, ẓedek, tirdof—it may be that justice might never materialize in the AMIA case. But perhaps, even if the justice Jewish Argentines are pursuing might perpetually hover on the horizon, their participation as citizens in the demands for justice still matters, carving out a space of belonging that also lies at the heart of their desire for repair.

NATASHA ZARETSKY is senior lecturer at New York University and visiting scholar at the Rutgers University Center for the Study of Genocide at Human Rights, where she leads the Truth in the Americas Initiative. She recently published Acts of Repair: Justice, Truth, and the Politics of Memory in Argentina (Rutgers University Press, 2021).