Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

“I feel very confident today. I somehow feel it will be fine and I’ll be able to do my bit to keep my participant at ease. I somehow am not much ‘scared’ of her. I feel it’ll all be fine.”

After the interview:

“She was quite welcoming, and I felt comfortable (more than I did with the first one). There was one thing that perturbed me while interviewing, it was that she constantly looked at my hands. I somehow felt that she could guess through my hand movements and the shape of my fingers that something is wrong. Does she now know that I have rheumatoid arthritis?”

The above two excerpts provide a good glimpse into the “conversations” I have with my diary. I am an interdisciplinary death researcher and it was eleven years ago that I initiated my quest to know about death. Just like any other field researcher, I also “own” a field diary which has over the years become my “secret keeper.”

After having lost a dear friend at the age of fourteen, I was drawn towards the uncertainty of death and how it affects humans psychologically. While in the last eleven years I interviewed many people about their experiences of witnessing or coping with death(s) and could finish all my projects, my research diary always remained “unfinished.”

Death rituals have always intrigued me. It was my interest in the cultural aspect of the rituals that drew me into the Jewish community. As a part of my PhD fieldwork, I interviewed Ashkenazic Jews living in London. Having worked in the area for many years, I was again preparing myself emotionally for the heart-wrenching narratives of the participants about deaths of the loved ones that my questions reminded them of, deaths that had brought pain to them. For each narrative that broke me, my diary became my confidant.

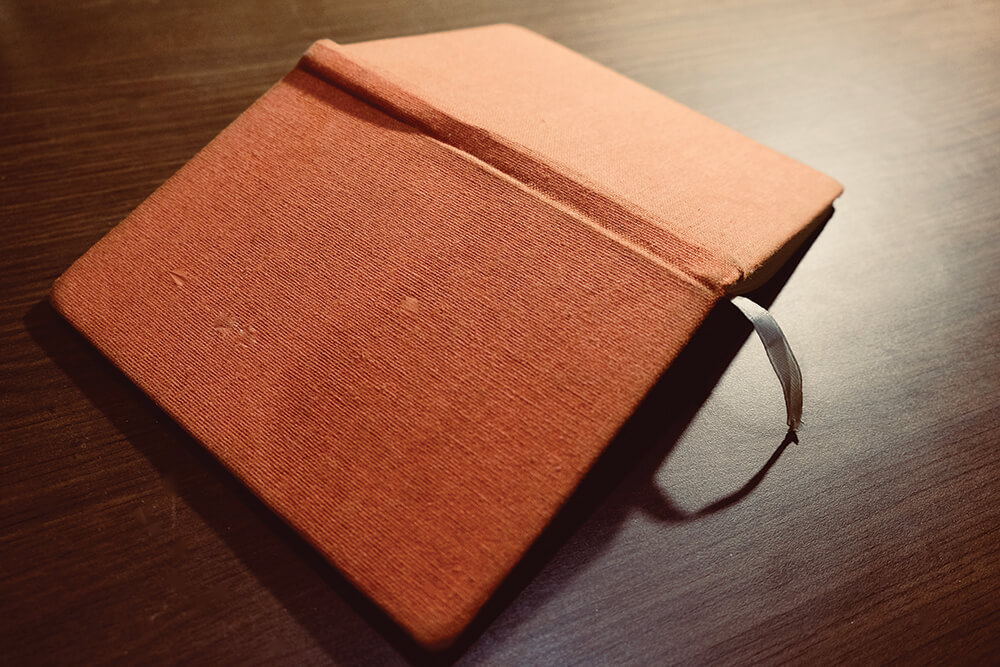

Courtesy of the author

I feel caged into the objectivity that a researcher is expected to embrace. One of the Jewish participants shared that he had put up a note on the side of his friend’s hospital bed saying “he was there” only to find it in the same place after his friend died the same night. The imagery of that note being stuck in the same place did something to me. It shook me because I felt that a life was breathing by this note’s side one day and the next day it was not. But I was handcuffed by researcher’s objectivity and still had to put up an expressionless face.

For others, it is just a small, dull orange-colored notebook, but for me, “she” has been a “person” I have confided in.

Living alone in London away from my parents, I would talk about the deaths (that I became a part of vicariously through my participants’ narratives) only with my diary. For others, it is just a small, dull orange-colored notebook, but for me, “she” has been a “person” I have confided in. She is aware of the emotional challenges I have had to face while pursuing these projects. She knows when I pretended to be a sensitive researcher even when I was writhing with frustration inside. She is the only one who knows how my heart wept when a participant narrated his daughter’s death and showed me her photograph from among many that were kept in his living room.

But even though I have felt like emptying myself into the pages of my diary, I was skeptical about “finishing” it. I did not tell her every emotion of mine, I kept a few hidden. She knows me but I do not want her to know me thoroughly. Just like I said in the first few lines, I own it and do not want it to be the other way around. What if she knows so much that I start understanding my life through those written words in the diary? What if I become so dependent on it that if, in whatever way, it gets lost someday, it takes away a part of me with it too?

I am scared of her because she has the potential to become the focal point of my world, but I do not want her to know that. Some days when I go to her, I feel anxious, like the day when I was emphatically told by a parish priest in London that being a cultural outsider, I was not the right person to explore the English Catholic death ways. Before deciding to explore the Jewish death rituals, I had wanted to understand the English Catholic death rites. I did not visit my diary for two and a half months after that because that was the day I felt dejected and unable to even consolidate my emotions into words and left my diary untouched for a long time. The first thing I wrote into my diary after returning was, “I am coming back to you after almost two and a half months, but the reason is not laziness. It is my ‘reluctance’ to show you my weaker side and the fear of rejection that I have been anticipating.”

My relationship with this unfinished diary is ambivalent. I abandon her for months together and when I come back to her, I apologize to her for not being there the last few months. There are field experiences that have just stayed with me and never entered my diary because I was afraid of consolidating those experiences in it. It is somewhat like my counselor with whom I share my feelings yet sometimes I am scared to show a side of me to her. I do not want to be perceived by my little diary as weak and vulnerable because those written words would not just become a part of my diary but remind me of my weak side each time I read it—they would really become a part of me. Having said that, my “unfinished diary” does not perplex me because I can control this “one-way” relationship. My diary is a listener, and as a speaker, I manipulate my words to selectively bare myself so that I can preserve my emotional equilibrium. I also believe that through my unfinished diary (that has no definite end) I strive to defy the finitude of life that death tries to cage us into.

Khyati Tripathi is a senior research fellow in the Department of Psychology at the University of Delhi. She was awarded the Commonwealth split-site PhD scholarship for the year 2016-17. She is an ardent researcher in the field of Death Studies.