Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

PEDAGOGY

On March 13, 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of Toronto’s Ryerson University, where I am a professor of English. Faculty were given one week to transition to emergency remote teaching. We were permitted to recalibrate the value of certain assignments, but obliged to cover all remaining course material. In my upper-level course on Canadian Jewish Literature, that meant one novel, one short story collection, and three poems.

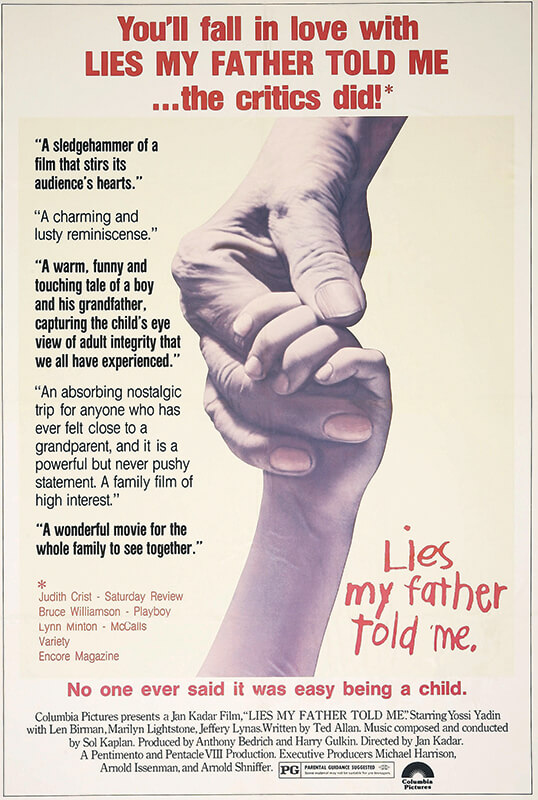

In the midst of confusion and chaos, I felt fortunate in several respects. First, I had had eight weeks to reinforce the historical/theoretical lens through which I analyzed the rise and development of Jewish writing in Canada, with an emphasis on the urban centres of Montreal, Winnipeg, and Toronto, as well as the experimental farming communities of the West. Second, I had already covered significant ground, including well-known works such as Ted Allan’s short story “Lies My Father Told Me” and Leonard Cohen’s poem “The Genius,” Adele Wiseman’s novel Crackpot and Isa Milman’s full-length poetry collection Prairie Kaddish. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I had developed a solid rapport with my students, most of whom were new to the religious traditions, practices, and beliefs referenced in the course materials.

Lies My Father Told Me, movie poster art, 1975. Everett Collection, Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo

Soon after the campus shutdown, however, it became clear that the very “remoteness” of online instruction would intensify the pedagogical challenges I had encountered in teaching Canadian Jewish Literature. How, for example, might I continue to offer nuanced interpretation of literary texts that referenced historical events and complex political ideas that were unfamiliar to most of my students? How would I address sensitive subject matter without personal engagement? (Zoom was brand new to Ryerson and had yet to be tested as a tool for teaching.) And how could I compensate for the lack of clarifying in-class discussion? Amended expectations helped mitigate potential difficulties, while a number of adaptations provided students with intermediary guidance via electronic means.

Immediately, I conceded that without our weekly contact students could not be expected to engage fully with the five works remaining on the syllabus. They were practiced, however, in our classroom approach to textual analysis informed by cultural context, and so I trusted that they had acquired the analytical skills and necessary background to successfully interpret the texts in question.

I sought to offset the lack of live discussion with an alternative mode of “classroom participation.”

I then proceeded pragmatically to redesign the last two assignments in the course. Transforming the comprehensive final examination into a take-home exam that covered only those texts we had taken up in class was relatively straightforward. Less so was the replacement of the final analytical essay (focused on a single work) with a series of reading responses, which I envisaged as a means of encouraging and facilitating student engagement with new literary works.

I sought to offset the lack of live discussion with an alternative mode of “classroom participation.” To that end, I developed guided reading responses, each of which provided notes on the text, accompanied by links to elucidating primary and secondary materials. My notes attended to the more challenging aspects of a work. Each reading response also included a list of questions formulated to enrich students’ understanding. Students were invited to answer any number of these questions in their 300-word reading responses.

For the students to grasp the full import of Kreisel’s work, it was essential that I explain the political atmosphere that dominates the novel...

They were asked, for example, to interpret the stark ending of Henry Kreisel’s 1948 novel, The Rich Man, which is set in the spring of 1935, soon after Hitler became chancellor of Germany. In The Rich Man, Jacob Grossman returns to his native Vienna to visit the family he has not seen for thirty-three years, having immigrated to Toronto as a young man. The crisis of the novel hinges on the fact that Jacob—a poor man himself—cannot come to the aid of his impoverished and increasingly vulnerable family members, all of whom are in the grip of heightened restrictions against Jews and virulent antisemitism. For the students to grasp the full import of Kreisel’s work, it was essential that I explain the political atmosphere that dominates the novel and the contrasting positions of Jacob, who returns freely to Canada, and his family members, who remain trapped in Europe and whose eventual deaths loom over the action, as does the Holocaust itself.

David Bezmozgis’s 2004 collection, Natasha and Other Stories, addresses the matter of contemporary Jewish identity head on and I was particularly interested in learning how students understood the volume’s presentation of “Jewishness.” As a coming-of-age chronicle, narrated in the first-person by protagonist Mark Berman, Natasha was accessible to students. For useful background information, however, I directed them to an extensive online HIAS interview with Bezmozgis, in which he recalls his own experience as a Latvian-born child who at age six immigrated with his family to Toronto. To aid students’ grasp of Mark’s developing Jewish sensibility, it was also vital to explicate his Soviet background, clarify his references to refuseniks, and probe the troubling nature of the bullying he experienced at the hands of fellow Jewish boys and—most traumatizing—the principal of his Hebrew school.

Finally, the course concluded with three elegies, two of which blend English and Yiddish, while a third takes place during the holiday of Sukkot. The significance of Yiddish as both a language and cultural marker had often entered our class discussions, so I spurred students to consider the role of Yiddish in poems by Karen Shenfeld and Kenneth Sherman that memorialize father figures who cleave to Old World ways and values. The third poem by Adam Sol laments a wife’s miscarriage that occurs during Sukkot. To help students grasp the poem’s sad irony, it was necessary for me to describe the celebratory aspect of Sukkot, with its week-long tradition of eating meals in a sukkah. My remarks were linked to supplementary author interviews and book reviews. To offer students further assistance, I held virtual office hours and communicated with them individually over email and telephone.

I sensed a new kind of actively engaged learning emerging among my students. They were more independent, capable of synthesizing knowledge and applying the critical skills they had honed during the semester. They also seemed more confident. And judging by their reading responses, the majority were not only absorbed by the works they read in isolation, they were changed by their reading.

Students’ own comments corroborated my belief that they had connected thoughtfully and profoundly with the material on the course. Many emailed affirming messages. This was “an interesting and enlightening class” wrote one; another was “grateful for all it has taught me.” Others addressed the course content and their newly acquired insight: “I had never … read any literature focusing on Jewish Canadians. I have learned so much from this course and it has exposed me to so many beautiful stories.” “I loved all of the readings … it was really interesting for me to learn more about Jewish culture and writing here in Canada.”

I admit to being especially gratified when students were moved to read beyond the offerings on the course. One was “already trying to figure out a way to safely get a hold of Henry Kreisel’s other novel [The Betrayal] to read over the summer, as I absolutely loved The Rich Man.” Yet another had secured a copy of Mordecai Richler’s Barney’s Version—a novel I had mentioned in class—and was “waiting for the chance to begin reading it. Thanks for the influence!”

For an English professor, is there any greater satisfaction than inspiring students to read further afield? In fact, the redesigned course may have steered me closer to my goal of enlivening students and rousing their curiosity about Canadian Jewish Literature. While the interrupted semester felt somewhat “unfinished,” it closed in an unforeseen but surprisingly positive way.

Ruth Panofsky, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, is professor of English at Ryerson University in Toronto, where she teaches courses on Canadian Jewish writing and Holocaust literature. Most recently, she is the editor of The New Spice Box: Contemporary Jewish Writing (University of Toronto Press, 2020) and author of Radiant Shards: Hoda’s North End Poems (Inanna Publications, 2020).