Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

“You should never strive for shlaymus, for completeness,” proclaimed Rabbi Schwartz, the principal of my Lubavitch high school while stroking his long gray beard. “It’s an illusion.” He had in mind the attempt to achieve completeness by perfecting one’s spiritual devotion through prayer and one’s mastery of Talmud. I did not grasp the full meaning of his words then, but they came back to me recently as I pondered the incompleteness of religious exit—both that of my research subjects and my own—and of the study of religious exit itself.

Over the last ten years I interviewed seventy-four Lubavitch and Satmar men and women who left their communities as young adults, and the analysis of those interviews is the subject of my book, Degrees of Separation: Identity Formation while Leaving Ultra-Orthodox Judaism (Temple University Press, 2020). I discovered that although they made significant changes in their lifestyle, such as changing much of what they ate, what they wore, and aspects of what they believed, there were nevertheless important elements of their upbringing that stayed with them even years after leaving. While claiming to reject the theological arguments around gender roles and racial separation, they nevertheless maintained conservative views on such matters. Many also still held on to the revulsion towards pork (“chazzer!”) that they imbibed growing up. One Lubavitch woman I interviewed explained that pigs had a “disgusting personality,” while others freely admitted that they had “irrational” fears and “psychosomatic” repulsion to the creature. Many interviewees spoke of still singing and being stirred by the Hasidic melodies of their youth or still returning to seminal texts from their communities. I concluded that the people I interviewed remained in a liminal state, forever having left their community of origin but never having fully integrated into the broader American society. Furthermore, my research challenges the basic notion that exiters ever “complete” the process of exiting.

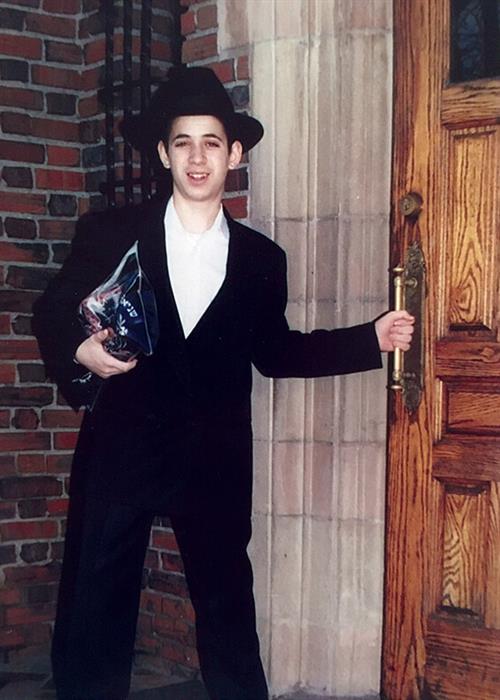

Left: Photo of the author from around the time of his bar mitzvah Right: The author today. Photo by Shulamit Seidler-Feller

Among the people I interviewed there was a wide spectrum in terms of how much of their past they incorporated into their present life and the impact these inclusions had on their state of mind. Several seemed preoccupied by it and continued to feel traumatized by their upbringing. Many others seemed to manage quite well and clearly enjoyed the ways that they were able to incorporate it into their more secular lives.

The key distinction among my interviewees is not how often they read the ultra-Orthodox press or visit their old neighborhoods, but what effect such actions have on their lives.

The key distinction among my interviewees is not how often they read the ultra-Orthodox press or visit their old neighborhoods, but what effect such actions have on their lives. Several of my interviewees feel a consuming need to keep up with all the goings on in the ultra-Orthodox world, and their visits to the community can leave them in tremendous pain, tearing open deep wounds and causing them to relive their earlier internal debates and religious doubts. Many others, however, experience simply an ongoing curiosity about developments in ultra-Orthodox communities, and their visits with friends and family still in the community are enjoyable. What they all have in common is that none of them are completely free of their past. It was something that they were required to negotiate and continue to engage with.

The process of researching and writing my book has helped me realize the extent to which my own exit from Lubavitch remains incomplete. I continue to marvel at how aspects of my Lubavitch upbringing keep bubbling up to the surface, sometimes when least expected. The anecdote about my Lubavitch principal—who would probably be horrified to be quoted in such a publication, and especially by me—that begins this essay is a case in point. The truth is that the Talmud (Shabbos 21b) is correct that girsa diyankusa, the knowledge we acquire at a young age, makes a deep impression on us. My interest in classical Jewish texts and history began while still a foot soldier in the Rebbe’s army but persists in my secular life today. At my Conservative synagogue every Shabbos morning, sitting beside my wife and daughters, with women leading prayers and reading from the Torah on equal footing with the men, I sing along with the same Yiddish accent and sense of attachment to the tradition that began in the Lubavitch shtibles of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where women were out of sight and only male voices were heard. When I take an aliyah, when I'm called to the Torah, I maintain the Lubavitch practice of touching my tallis to the words that bookend the section of the aliyah before the reader begins, although this is not the practice of the community.

As I think about my book as a completed, published work at long last, I realize that the scope of my own research project is far from complete. After years of tracking down and reassuring sometimes nervous interviewees, arranging conversations at their homes or in local cafes; after enduring long days and sleepless nights poring over transcripts searching for patterns, there is still so much territory that awaits to be explored. We still do not know the differences in the experiences of Hasidic exiters from families with parents who joined the Hasidic community from the outside (baal teshuvahs) versus those from families whose parents were born into their communities (“frum from birth”). We still do not know enough about the relationship between leaving such communities and secular education. What percentage of Hasidic exiters ends up dating or marrying non-Jews and what effect do these relationships have on their own religious and cultural identity and ties with their families? My research thus far has focused on exiters from Hasidic communities. What are the salient differences among such exiters and those from non-Hasidic, “yeshivish” communities and from ultra-Orthodox Sephardic homes? And there are still no longitudinal studies on this population. Do the findings that I and others have observed persist among exiters not only years but decades after they exit? These and many other questions await further studies.

It’s easy to view these cases of incompleteness—both of religious exit and of the scholarly examination of it—as a weakness, as a rebuke, or as a failure to get the job done. But we can also see it another way. The incompleteness of the transformation of the lives of religious exiters, myself included, allows us to not limit ourselves to the sterile choice of either maintaining the religious inheritance we were born into or forcing ourselves uncompromisingly into the outside secular world. It allows us the freedom to meld together diverse elements into a richer and more beautiful amalgamation. And the fact that no academic study is ever complete means that there is always room for additional scholarship and inquiry, that scholars need not rush to judgement, because there will always be future opportunities to pursue a fuller and more nuanced understanding of the object of analysis. After all, the Talmud (Ḥagigah 17a) teaches tofasta meruba lo tofasta, if one tries to grasp too much at once, one is liable to fail to grasp anything.

Schneur Zalman Newfield is an assistant professor of Sociology at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY, and the author of Degrees of Separation: Identity Formation while Leaving Ultra-Orthodox Judaism (Temple University Press, 2020).