Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

THE PROFESSION

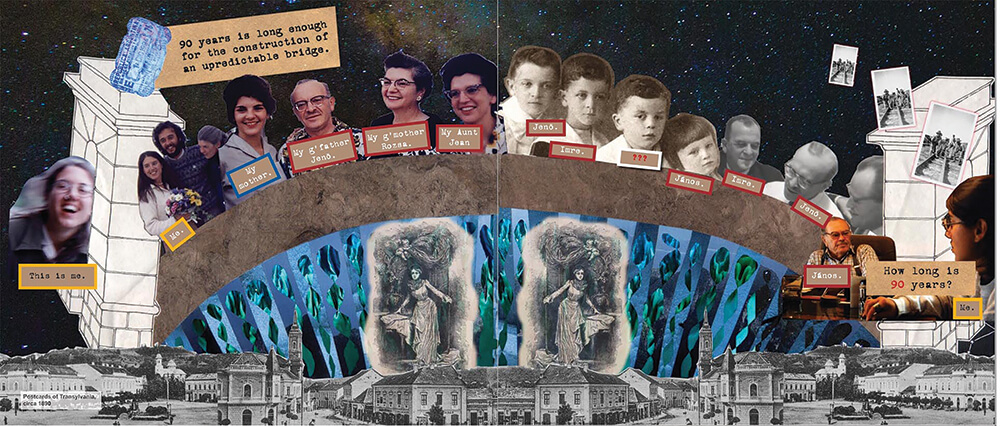

Before COVID-19 ground everything to a quick halt in the spring of 2020, I had already experienced sudden illness leading to an as-yet and indefinitely unfinished project. In summer 2017, I spent three months in Buenos Aires to begin research for my second book, a project on Jewish women’s visual culture in Argentina. I met with Irene Jaievsky, the curator of Jewish women’s artwork at the Museo de la Mujer (Women’s Museum) in Buenos Aires, as planned, and she connected me to contacts with Jewish women artists throughout Argentina. I decided to spend some time in Córdoba. I interviewed two women, Alex Appella and Sarita Goldman. Alex became a major interlocutor about a community of Jewish artists, many of whom are women. Her collages and an art book traced family threads from Transylvania to the United States, Argentina, and—to her surprise—Israel. She learned she had one more uncle than she knew of, a secret uncle because he fled Transylvania for Mandate Palestine. The rest of the family individually made the decision to hide their Jewishness, until her great uncle revealed the truth. She uses multidirectional visual and verbal writing to tell narrative and metanarrative, underwritten by a distinct theory of time and heritage that cannot be rendered linear. Thus, my work for the second project began to take shape.

Digitally produced collage pages from Alex Appella, The János Book, English trade edition, 2006. Courtesy of the artist

Upon my return, I began to reflect on broader ideas that emerged from my time in Córdoba: how Jews have seen themselves as part of local and national communities; how various communities have envisioned the importance of Jewish presence; how these women artists complicate any idea of national borders somehow containing or dictating Jewish life and practice. I thought about how Jewish women are doubly marginalized from the art world in Argentina as Jews and as women, and as residents of Argentina they are marginalized from histories and representations of Jewish communities throughout the world.

However my health rapidly deteriorated. I could barely walk. On my third trip to the ER, I was finally admitted. I learned that if they cannot determine what department of the hospital should treat you, it is difficult to be admitted. But when my heart rate had dropped to the 20s and I collapsed as I entered the hospital, they were able to admit me at last, for heart failure.

I received a diagnosis of E. coli. The bacteria had ravaged my body for six weeks, though antibiotics reversed many effects. Yet, I stayed for ten days and underwent tests in virtually every department of the hospital. Doctors told me, “you are in too much pain” and “you don’t seem to be aware of how much pain you are having.” I left with an awareness that my body is not like other bodies, not before the E. coli and not after. I took a partial leave from teaching, then a semester of FMLA when I would have had a sabbatical. I was on medical leave for about eight months. I was de facto in near-total isolation.

I got back to writing in late summer 2018 and completed my first book manuscript. My illness continued to affect my life, and I finally was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and some other conditions. I needed surgeries. My former partner and I ended a ten-year relationship. As two academics, we struggled to find work in the same place, and my “new” disability affected my needs and my personality. As he remained on the job market, life became untenable.

In the fall of 2018, I returned to Argentina. I broke my ankle in a freak accident, and this new physical burden broke me in good ways and bad. Although if I return to Argentina, I don’t expect to be in a car accident in the Andes again, I finally saw that I was trying to continue life in a pattern that did not match up with my abilities. I came to a conclusion: my research in Argentina must be on hold.

I prefer to say that my work is “indefinitely” on hold as a positive adaptive coping mechanism.

I prefer to say that my work is “indefinitely” on hold as a positive adaptive coping mechanism. It is psychologically less burdensome to see unfinished work, or the disruptions of a global pandemic, as “indefinite.” This refuses to overreach and see a hard situation as lasting “forever,” yet it also acknowledges uncertainty directly. I don’t know how much time I’ll need to be in a position to return to ethnography in another country. It’s ok to have limits and not to know how long they will last. When I first got sick, I wanted a timeline to recovery. Actually, I could not even have a timeline to diagnosis. My thinking had to shift. Accepting the deep contingency of our lives and uncertainty of how personal, national, and global situations will play out, in many ways beyond our own control, is key to living adaptably and mentally healthily.

But accepting this personally left accepting this professionally. While I mourn the time and distance growing between the community of artists I met in Argentina, my tenure clock ticks on. I have to explain to my institution why the research I had planned won’t go forward for now, and what I’m doing in the meantime. The experience of Jewish women artists working in Córdoba—a major city but less populated and less famous than Buenos Aires—mirrors and brings to the surface the question of what it means to construct a Jewish visual culture from the margins. Geography, gender, and Jewishness pushed many artistas judías to the margins, but they have distinct insights from there. Disability pushed me to quotidian and academic margins. I want to learn more about the Jewish women working and working together in Córdoba, but I can’t for now.

But it’s not as if I can no longer think and write. As I move on to research that can be done from home, I am excited about new possibilities and I have a lot to say. But in explaining my trajectory, I do not relish needing to incorporate some disclosure of my personal health and struggle in my self-evaluation for my tenure file.

However, I don’t see any other way, and perhaps it is important that we do this. I hope that my disability will not be held against me. People tend to see me and assume that I’m “all better.” I know they think this because they tell me they’re glad I am. No, I explain, I am not all better and may never be. I’m better, but I am not who I used to be. I worry that the dissonance between appearance and experience, the nature of unmarked disabilities, will affect how people read my narrative in my tenure file. These are worries that most people with disabilities have, and they’re rooted in our ways of thinking about disability in general. There is not a world of abled/disabled. It’s a spectrum, and most of us will be disabled somehow, perhaps only for a little while. If academics and all thinking could shift to expect contingencies, including disabilities, all of our lives would be improved.

My situation is a microcosm. We need to acknowledge that the patterns we plan for ourselves may change, and our institutions should help us adapt, not exacerbate the fear and shame that can come with health problems, diagnosed or undiagnosed. My health is stabler now, but COVID-19 represents a new contingency that I cannot control, in addition to being an unnatural disaster in the United States. How long will this sickness last? What will the changes in passport or border policies mean for all of us who seek to live, work, attend conferences, and more outside of our national borders?

For me, the quarantine felt familiar: enclosing myself at home to work within restrictive limits.

For me, the quarantine felt familiar: enclosing myself at home to work within restrictive limits. This familiarity first made the transition easier for me than for my colleagues. Then, it brought up deeper feelings of frustration: How could I have finally recovered “enough” from food poisoning and some of the effects of fibromyalgia, only to break my ankle? Now I have two legs to stand on, but I must return to lockdown and a project that remains unfinished? However, the same support will get me through as before COVID-19: sympathetic friends and colleagues and a vision that “unfinished” may not mean permanent loss. The more I embrace that perspective, the more my resilience and possibilities appear before me. Now, not just my work but the research of every academic is indefinitely on hold. In this together, we can ask how illness and unfinished work provide insights and possibilities less visible from the perspective of our best-laid plans.

Jessica Carr is associate professor of Religious Studies and the Berman Scholar of Jewish Studies at Lafayette College. She is the author of The Hebrew Orient: Palestine in Jewish American Visual Culture, 1901–1938 (SUNY Press, 2020).