Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

While the complete works of Philip Roth exist in ten volumes from the Library of America and the majority of his novels remain in print as trade paperbacks, we lack the complete story of his life. This was a problem for Roth, who spent his final years outlining his life story. Eager to rebut Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, Roth hired a biographer, Ross Miller, but the arrangement proved unsatisfactory. By 2012, he’d chosen a replacement, preparing a series of lengthy documents showing exactly how he wanted his life presented. His story would have an ending, but it would be one he wrote. As the narrator in Alan Lelchuk’s satirical novel about Roth, Ziff: A Life? (2003) asks, “Can Ziff have it both ways?” Roth emphatically answered “yes.”

Roth had a fictional precedent: his 1986 novel The Counterlife, where Henry Zuckerman, brother of Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s alter ego, dies on the operating table but remarkably comes back. Henry starts as a dentist in New Jersey, but once revived, becomes a militant settler in the West Bank. Meanwhile, Nathan Zuckerman also dies, but nonetheless narrates his and his brother’s story, although Henry will discover and edit Nathan’s story in the end. The novel's unstable narrative is a set of countertexts and counterlives, with multiple beginnings and endings. As Bernard Malamud wryly notes in his novel Dubin’s Lives, “Life responds to one’s moves with comic counterinventions.”

Before he died, Roth prepared instructions, directions, and even guidelines for his biographer, seeking to control how his story was presented.

Before he died, Roth prepared instructions, directions, and even guidelines for his biographer, seeking to control how his story was presented. Yet Roth believed that no life was ever finished: both The Counterlife and Everyman (2006), as well as Indignation (2008), are narrated by deceased protagonists. They are preludes to Roth’s own determined attempts to control and revise the narrative of his life, to finish the unfinished business of living.

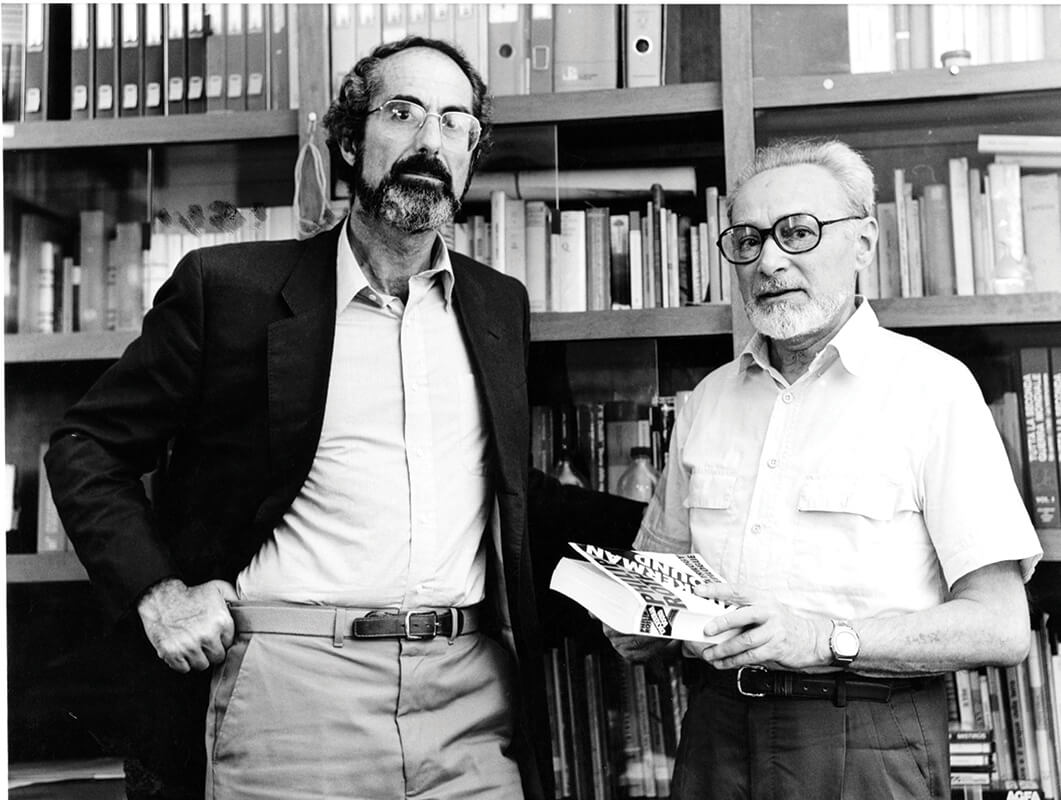

Philip Roth visiting Primo Levi in September 1986 at his home in Turin, Italy. Courtesy of La Stampa and the Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi, Turin, Italy

Between his “retirement,” in 2010, and his death, on May 22, 2018, Roth prepared file after file for his new biographer Blake Bailey, each with a memorandum on how to read and use the material. He also prepared a series of private documents that outlined in detail what information should and should not be included. Several of their headings are “Money,” “Marriage a la Mode,” “Pain and Illness History,” and a lengthy “Notes for My Biographer” (over three hundred pages). In these documents, he details the narrative he wanted told. In short, Roth sought to complete his own unfinished life from the grave, fearful of losing control of the story. A scene in Everyman epitomizes the effort: visiting a cemetery, the protagonist questions a gravedigger on his method. The man responds, “I dig front to back, and I dig a grid and as I go I use my edger to square the hole.” This is exactly what Roth sought to achieve, providing an edger (his instructions) to square the hole (his life): “You have to keep it square as you go,” the gravedigger reminds the unnamed protagonist and the reader (Everyman, 175).

Have other writers left similar directives? Certainly not. James Atlas began his biography of Saul Bellow with his subject's cooperation, but met increasing resistance after Bellow sensed that Atlas was writing an unsympathetic portrait. No instructions, just resistance. Atlas soon found his subject feeling guilty about parts of his life and kept things secret. Unable to control his story, Bellow turned stubborn and prickly, attempting to shut down rather than redirect his story. Unable to withdraw permission, he simply lessened his cooperation. In Atlas’s words, Bellow saw that “the biographer was the gravedigger.”

The result made Bellow uncomfortable largely because it portrayed him as a crabby, vain, promiscuous, self-centered narcissist constantly in need of money to support his multiple ex-wives. Bellow’s second biographer, Zachary Leader, did not have Atlas's problem: Bellow could no longer interfere (he died in 2005) and the estate wanted a new, more sympathetic life to replace the Atlas portrait. The biographer did so in two lengthy volumes of over 1,500 pages, presenting a life submerged by its facts. Roth strongly encouraged the writing of this second type of life.

Bernard Malamud never encouraged a biography. He may have sought control—he did have secrets—but for years after his death, the family opposed any life. But worry that Malamud’s reputation was fading led to the family granting a British critic (Philip Davis) permission, and a completed biography appeared in 2007, twenty-one years after Malamud's death. In contrast to Malamud's anodyne public image, the biography revealed his twenty-year affair with a student. Anticipating this revelation, Malamud’s daughter published a memoir the year before the biography with details and even a new revelation: Malamud’s wife had herself had extramarital affairs. Janna Malamud Smith’s My Father Is a Book offers a multihued portrait; Philip Davis, somewhat hampered by the estate, paints largely in black and white.

Not every biographical subject, of course, is as prescriptive as Roth. A more hands-off approach was that of Samuel Beckett, who offered neither interference nor guidance when Deirdre Bair proposed writing his life. “I will neither help nor hinder you,” he promised at the end of their first meeting in 1971, his neutral position ideal for any biographer.

Of course, every biographical subject wants to control their story after they’ve gone, finishing their unfinished business without the worry that others might do it improperly. Despite Roth’s acknowledgement in his fiction that every life is always unfinished, he ironically sought completeness. But while not granted access to the special files and memoranda, I’ve found unexpected discoveries and new sources, some previously restricted until after his death. These have opened new avenues of understanding. Unlike my accounts of Leonard Cohen, Tom Stoppard, and Leon Uris, where access was unrestricted, writing about Roth is something of a roundabout process. But even with limited interviews and partial entrée into his world, a certain freedom emerges to offer readings and interpretations not encouraged or even permitted to the “official” biographer. Roth’s faith in directing his biography was unbounded; he believed that his life would at last be told as he wanted. In this way, Roth became the actor, director, and producer of his own story, his own “ghost writer.” But to date, his film remains unreleased and may, indeed, require editing.

Ira Nadel, professor of English at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, has published Biography: Fiction, Fact & Form (Macmillan, 1984), Joyce and the Jews (Macmillan, 1989), and Modernism’s Second Act (Palgrave, 2013), in addition to biographies of Leonard Cohen, Tom Stoppard, David Mamet, and Leon Uris. His account of Philip Roth will appear in 2021.