Above: Detail from Drawing, late 19th century. Brush and gouache on cream paper, mounted on cream paper. 9 1/16 x 8 1/8 in. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Friends of Drawings and Prints with special assistance from Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. and Phyllis Dearborn Massar

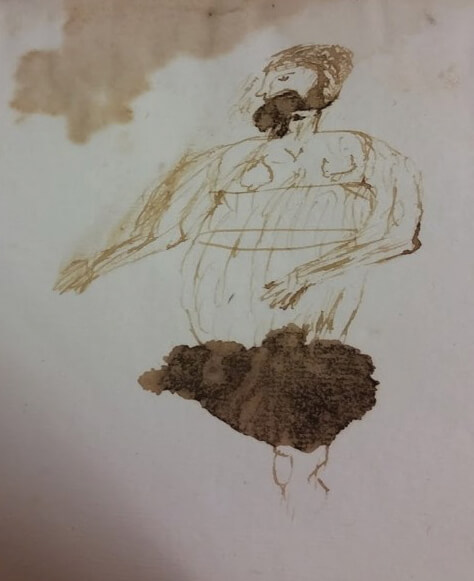

In a flyleaf of the Babylonian Talmud tractate Ḥagigah (Venice: Bomberg, 1525) I found a shocking ink drawing of a figure fully clothed with breasts exposed. There were two ink blotches in a darker color of brown ink. One served as a beard that covered the figure’s face and a second covered the folds in the figure’s dress. Both feminine and masculine in a Talmud, no less—I wanted the backstory (see figure 1). Who was this person? Was this a woman who wanted to be a man so that they could study Talmud? Did Talmud study turn this woman into a man?i Or was this a man imagining himself as a woman?

Fig. 1. Tractate Hagigah (Venice: Bomberg, 1525). Courtesy of Columbia University Rare Book Room

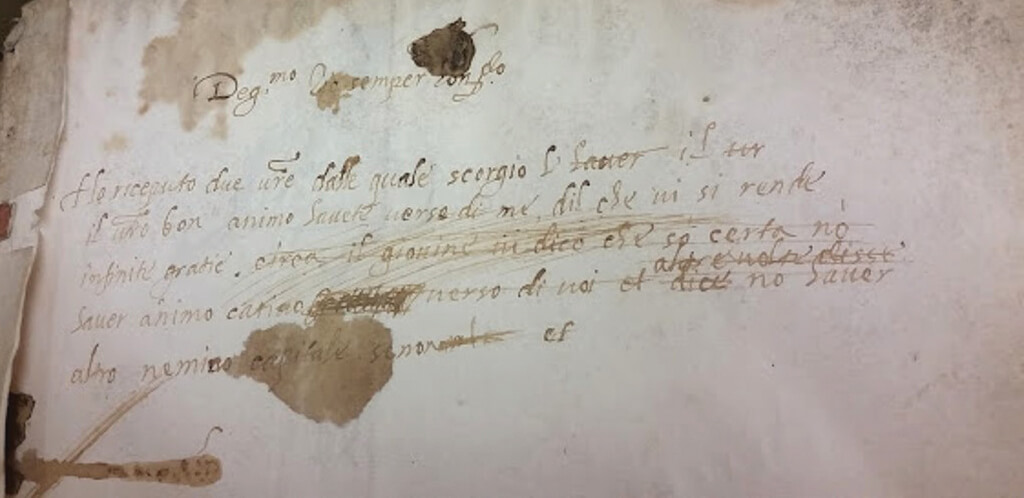

An inscription in Italian found along with this image indicates that a woman scribed the message (figure 2). It is the clearest sign that a woman held this volume. Mention made of her uncle suggests that she might have been using the volume to send a message to him presuming that he would see it. Noting that she had already received two of his letters and thanking him for his “generous inclination” toward her, she mentions another individual. She seems to want to convince her uncle that this unnamed man does not have evil feelings for him and that he is a good man. The scrawl ends abruptly.ii

Fig. 2. Tractate Hagigah (Venice: Bomberg, 1525). Courtesy of Columbia University Rare Book Room

Did this copy of Ḥagigah belong to the uncle? Does this woman wish to get her uncle’s attention in a book that her uncle used often? Possibly, the book was hers. Was she using the flyleaf of her own book as a place to pen a rough draft of an important letter? Was the letter referring to her uncle’s love for her and her love for another man? Was she hoping to marry someone he thought unworthy of her? Or maybe she was referring to a talmudic discussion among men, inserting herself into the middle to convince her uncle that he needed to hear the substantive ideas expressed by this unnamed man who was not an enemy.

We look at Bomberg Talmuds for a variety of reasons, including the fact that they are textual witnesses of early versions of talmudic texts. An image on a flyleaf and an inscription in Italian might be easily dismissed as meaningless doodles, irrelevant to the scholarly task at hand. In truth, we do not know who this woman or her uncle were. We do not know exactly where and when the image and inscription were added to the flyleaf. But I cannot readily dismiss these personal flourishes. They remind me that book copies have individual stories and that some of those stories are about the people who scribbled androgynous images on their pages.

This image and inscription call attention to the presence of nonauthoritative “texts” in book copies, including inscriptions on title pages, on flyleaves, in bindings, and in the margins of books that breathe real life into them. Such additions remind me that copies of the Talmud were used and traded, bought and sold, preserved and passed on. They are clues as to who read and owned tractate Ḥagigah and a stark reminder that copies of Talmuds were not solely in the hands of a rabbinically literate male elite.

It is difficult to draw historical conclusions from one image in a book copy. This scrawled image and unfinished note remain frustratingly open-ended and unresolved. But by recording every nugget of information that we find in copies of Jewish books we turn what has remained largely unseen into a visible historical record. Some half-composed thoughts and figures in a copy of tractate Ḥagigah cannot tell their own full story successfully, but when aggregated with other peculiar inscriptions or ambiguous dedications enable us to tell another story about the Talmud than its transmission from teacher to disciple or father to son. Making women visible builds a more nuanced picture of the Talmud’s audience. It also prompts us to consider where copies of the Talmud were kept—in a beit midrash or in the Jewish home—posing questions regarding where women could be found if they had access to a volume of Talmud.iii

When I found this image in tractate Ḥagigah I was in the rare book and manuscript room at Columbia University inputting information into a database called Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place. The database is the brainchild of a scholars’ working group that I cochaired at the Center for Jewish History, birthed to gather all of the information connected to the pathways of Jewish book copies from the time they left the printing house until the present day.iv Among the type of information that can be loaded into the database is evidence related to any woman who had a relationship to a book copy, identifying them not only as owners and readers, sellers and buyers, but as wives, widows, daughters and nieces, whether they are named or not.

Jewish book copies leave us many unfinished stories, including broken pathways as books traversed their way across the globe.

Jewish book copies leave us many unfinished stories, including broken pathways as books traversed their way across the globe. Appearing in one century in a given place, and lost for two more, many books resurface or leave records in auction catalogues, estate inventories, or in other books, attesting to their existence. Footprints enables us to read thousands of unfinished stories alongside one another such that what is missing from one story might be completed in another … or not. While I cannot uncover all of the details behind this woman wishing to be a man, or man wishing to be a woman, in tractate Ḥagigah, I do not have to solve the puzzle in order to record a fascinating piece of evidence.v The unfinished story does not have to stop me from formulating compelling research questions related to Jewish women in early modern Europe prompted by such a discovery. And, while treating this copy of tractate Ḥagigah as important data for Footprints, I can, along the way, also construct my own hypothetical story where I imagine women, in fact, transmitting Talmud to their uncles.

Marjorie Lehman is associate professor of Talmud and Rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary. She is the author of The En Yaaqov: Jacob ibn Habib’s Search for Faith in the Talmudic Corpus (Wayne State University Press, 2012) and her new book, Bringing Down the Temple House: Engendering Tractate Yoma (Brandeis University Press) is forthcoming. She is also the co-project director of the digital humanities project, Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place.

i Sarit Kattan Gribetz, “Consuming Texts: Women as Recipients and Transmittters of Ancient Texts,” in Rethinking “Authority” in Late Antiquity: Authorship, Law and Transmission in Jewish and Christian Tradition, ed. Abraham J. Berkovitz and Matthew Letteney (London: Routledge, 2018), 191. I thank Sarit Kattan Gribetz for her insights regarding this image.

ii Many thanks to Federica Francesconi and Fabrizio Quaglia for helping with the translation.

iii Kattan Gribetz, “Consuming Texts,” 179.

iv The codirectors of Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place are: Michelle Chesner (Columbia University), Marjorie Lehman (Jewish Theological Seminary), Adam Shear (University of Pittsburgh) and Joshua Teplitsky (Stony Brook University). See https://footprints.ctl.columbia.edu/.

v In Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place, ed. Michelle Chesner et al., footprint #979, creator, Marjorie Lehman, last modified by Michelle Chesner, https://footprints.ctl.columbia.edu/footprint/979/, July 7, 2020.