Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

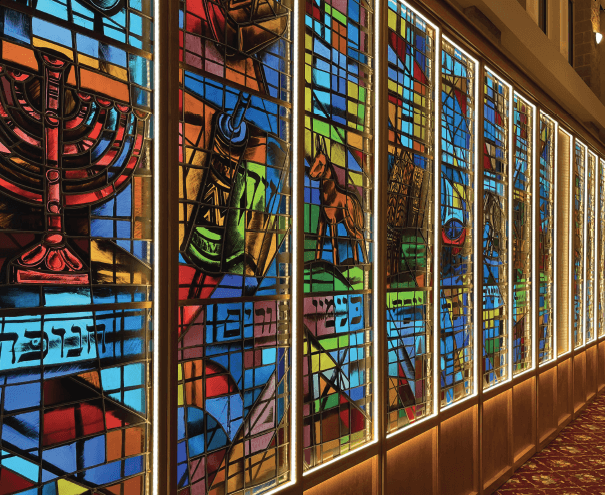

Stained glass designed by Dave Ruskin and fabricated in Barrilet Studios, Paris. Installed in Temple B’nai Israel, Saginaw, MI (1961) and removed and reinstalled in Northbrook Community Synagogue, Northbrook, IL (2021). Photo by Aaron Braun. Courtesy of the author

Northbrook Community Synagogue’s cavernous sanctuary seats 1,200 stackable chairs. Large, blank, white, and nondescript, the hall feels sterile. “Like a hospital,” reports synagogue member Jerry Orbach. Yet, the building’s vast stretches of empty walls also provide a benefit; they accommodate Orbach’s obsessive habit of collecting stained-glass windows.

Over the past ten years he has filled the space with glass panels that now flank the bimah, hang off the walls, and are perched on a ledge near the ceiling. Vibrant reds, luscious greens, and flaming yellows form Jewish stars, holiday imagery, insignias of the twelve tribes, representations of Torah scrolls, spice boxes, the Western Wall, and an eternal lamp; a jumble of symbols in glass. The panels also form a medley of different shapes and sizes. One group of ten are square, each just a bit larger than an LP record. A set of five are semicircular, each the right size to serve as a decorative element above a doorway. Another is a massive installation that once graced an exterior wall, reaching from the second floor up to the roofline on the third.

The various glass sets were designed by different artists and during distinct time periods. Yet, they hold two things in common. First, they were all fabricated for synagogue buildings that have fallen out of Jewish hands as their congregations moved or dissolved. Second, all of them have been “rescued” by Jerry Orbach—a term he uses to indicate the windows’ return to the Jewish community.

“I had my bar mitzvah under these windows. I got married under them,” he told me, explaining his emotional connection and how he came to arrange a trade with the church congregation.

Thus far, Orbach has brought window panels from five former synagogues into Northbrook Community Synagogue. He has personally covered all expenses in donations, totaling more than $100,000, in addition to spending hundreds of hours on phone calls, research, coordination, as well as physical labor. And his work is not complete. The synagogue building has a lower level, Orbach tells me, with more stretches of empty wall space. And don’t forget the synagogue grounds, which also offer the opportunity for new installations. At the moment, there is no end in sight for his collecting.

I connected with Orbach last summer through research for my book manuscript, Disposing of the Sacred: America’s 21st Century Jewish Congregations. In the midst of the Covid pandemic, I haven’t yet had a chance to travel to Chicago and see the collection in situ. Instead, Orbach has sent me photos, and we’ve had hours of phone conversations about his work creating the self-proclaimed “only repository of synagogue stained glass in the world.” Orbach is a garrulous storyteller whose interests do not much align with those of an art critic or art historian. Few of our discussions focused on who designed and fabricated the windows, what they depict, their color palettes, or the texture and quality of the glass. Instead, Orbach regales with tales of acquisition: how he identified the windows, procured them, transported them, and had them reinstalled in his own synagogue.

Story after story, and one phone call after the next, I wonder what animates his collecting. But Orbach speaks with such assuredness about his pious recycling that I am reticent to ask, fearing such a query would come off as rude, as though calling into question the very endeavor itself. I will come around to broaching the issue eventually, but not until I’ve heard all his acquisition stories.

The first set came from Kehillat Jeshurun, the Albany Park synagogue Orbach’s family attended while he was growing up. When the Jews moved out of the area after World War II, the building was bought by a church. Orbach kept his eye on it. “I would prowl the neighborhood,” he explained, surveying the fate of the area that had been predominantly Jewish until almost all moved out to the suburbs, leaving their storefronts, schools, and synagogues behind.

Decades later, Orbach returned to tour the previous Kehillat Jeshurun building and was struck by the stained glass, which had remained intact. “I had my bar mitzvah under these windows. I got married under them,” he told me, explaining his emotional connection and how he came to arrange a trade with the church congregation. He had the stained-glass windows removed, and in exchange replaced them with new ones, decorated with Christian iconography more suited for the church.

Unlike Kehillat Jeshurun, which sold their building to a church, Mikro Kodesh Anshe Tiktin in Peterson Park was razed not long after the congregation dissolved in 2004. When Orbach received news of the building’s impending demolition, he rushed to hire a crew to remove the Stained glass designed by Dave Ruskin and fabricated in Barrilet Studios, Paris. Installed in Temple B’nai Israel, Saginaw, MI (1961) and removed and reinstalled in Northbrook Community Synagogue, Northbrook, IL (2021). Photo by Aaron Braun. Courtesy of the author windows. “It was an emergency,” he recounted in dramatic tones. The end came quickly, “We put up scaffolding,” and within no time, “we were pulling out the windows from the front while the building was being torn down in the back. I was terrified. The wall was crumbling as the windows were coming out.”

While Orbach was once focused on windows from buildings in Chicago’s bygone Jewish neighborhoods, now he’s broadened his attention to synagogues across the country. In December, 2020, he acquired a set from B’nai Israel in Saginaw, Michigan (which dissolved in 2005), and he is currently working to procure another set from a recently disbanded synagogue in upstate New York.

“It’s a living genizah,” Orbach corrects me—it holds the past while mingling with prayers of the present.

Finally, I ask. Why? Orbach pauses—a brief interruption in our lively back-and-forth—“There’s a feeling you get from them…. They enhance the room, the sacred space.” That’s not satisfying. I push him. “So why not commission new ones?” Why mount windows that are clearly not designed for the space they now occupy, windows intended to grace a doorway, that now sit perched above a ceiling ledge? An installation of glass intended for an exterior wall, which now serves as an archway to nowhere?

“They are beautiful,” he answers.

But what is beauty? So much is wrapped up in this word. In his famous essay “Unpacking my Library” the German Jewish cultural critic Walter Benjamin describes what it is like to watch a collector handle his objects: “He seems to be seeing through them into the distant past as though inspired.” Yes, indeed, Jerry looks deep beyond the surface of the windows, to see what they hold: “The history of the shul that’s gone,” he says, and then offers, “If you remember the shul, you are remembering all the people who were there.”

Once Orbach has the windows removed from the original spot for which they were designed, he has them encased in wooden cabinets and electrically wired to be lit from behind. In their new form, they are sculptures of light, glass, and memory. Plaques installed beside each set tell the history of the congregation whose building they once adorned.

“You’ve created a genizah for stained glass,” I suggest, referring to repositories of documents that are no longer useful, but that cannot be thrown away because of their sacred status. Found later, such items have served as important primary sources for historians writing the stories of communities that are gone. “It’s a living genizah,” Orbach corrects me—it holds the past while mingling with prayers of the present.

ALANNA E. COOPER is the Abba Hillel Silver Chair in Jewish Studies at Case Western Reserve University. Her forthcoming book is entitled, Disposing of the Sacred: America’s 21st Century Jewish Congregations.