Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

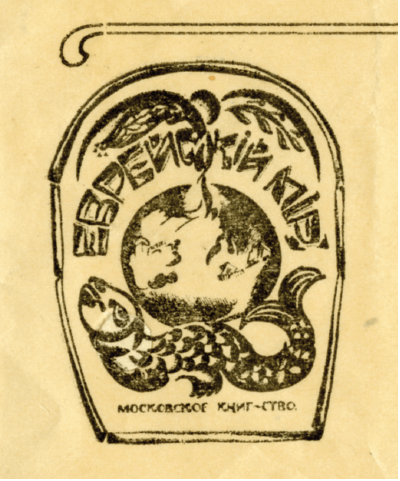

“A velt mit veltlekh,” goes the Yiddish expression of wonderment at a point where different spheres meet: “a world with little worlds.” Just such a compact, teeming world might be found in the logo of Evreiskii Mir, a fleeting publishing project that put out an ambitious Russian Jewish literary journal of the same name in Moscow in 1918. Edited by the writer Andrei Sobol and the theater critic Efraim Loiter, Evreiskii Mir (literally, Jewish world) was an exceptional anthology of translated Yiddish-to-Russian and original Russian literature. A collection of pieces by Jews and non-Jews, Evreiskii Mir counted among its contributors Yiddish writers Dovid Eynhorn and Dovid Ignatov, as well as major voices of Russian modernism such as Valery Bryusov, Vladislav Khodasevich, and Jurgis Baltrusaitis. While Hebraists and Yiddishists staked out claims for the language of Jewish cultural nationalism, Sobol initiated one of the few known projects of the time that actively solicited original works in Russian, as well as translations of Yiddish literature into Russian.i

Detail of stationary logo from a letter Andrei Sobol wrote to S. Niger (YIVO, RG 360 Box 49 Folder 1228). YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

The Evreiskii Mir logo does not appear on the pages of the periodical Evreiskii Mir itself. Yet it surfaces in Sobol’s frantic correspondence in archives in both Moscow and New York, under the bilingual Yiddish-Russian letterhead of “Moskver Farlag—Moskovskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo” (Moscow Publishing) or, sometimes, under the Russianonly letterhead naming it “Evreiskii Mir.” It winks back in letters sent in Sobol’s quick hand to figures ranging from prominent dance critic Akim Volinsky to Russian poet Nikolai Ashukin to Yiddish literary critic S. Charney.ii The logo’s persistent presence on Evreiskii Mir’s stationery invites examination.

The Evreiskii Mir logo does not appear on the pages of the periodical Evreiskii Mir itself.

In the logo’s middle spins a globe, balanced on the scaly, undulating back of the Leviathan, a primordial beast. Overhanging this lively assemblage is a ritual set from the holiday of Sukkot: a palm frond, myrtle leaves, willow branches, and an etrog.

The iconography of the logo reveals the folk models and political dreams enlisted in the creation of a new Jewish culture. Both the Leviathan and the Four Species point towards messianic strivings, yet their usage in the logo is untraditional. The Leviathan was a familiar motif seen carved into the wooden ceilings of eastern European synagogues.iii As Boris Khaimovich explains, at times the Leviathan wrestled with the land beast Behemoth, locked in a match that foretold the end of days; other times, it was curled, head meeting tail, encircling the holy city of Jerusalem (and the greater cosmos, by extension) in a stabilizing hold.iv In these synagogal ceilings the Leviathan served an eschatological or cosmogonic purpose; in the Evreiskii Mir logo its placement marks a shift in the shape, time, and location of the messianic age. The vision that the Leviathan supports is set not in the Land of Israel but between foci of the modern Jewish experience. With no clear capital, this new territory appears to have two poles: the shtetl of the Pale, with its low, wooden houses to the right, and Moscow, studded with proud onion domes, to the left. The Four Species, coupled with the Leviathan, refer to the banquet of the messianic age, when it is said the righteous will eat in a sukkah made of the Leviathan’s hide. Here, they, too, are suspended not above the religious locus of the ingathering of exiles—the Holy Land—but over a space where a Jewish minority culture might thrive in a diasporic, European context.

The second issue of Evreiskii Mir was never published: Sobol was forced to leave Moscow, the venture dissolved and the local cultural milieu for its reception did not last too long. The final pages of the first and only issue, however, preserve an intriguing preview. Included is the the upcoming issue’s table of contents, as well as titles of separate manuscripts: some tracts by an L. E. Motilev had already been printed, and a translation of Abram Efros’s “The Cry of Jeremiah” was yet to come. In part, then, a focus on the little letterhead logo draws attention not only to the singular velt of the journal, but also to the larger projects that might have been. Alan Mintz wrote, “In a moment of extraordinary cultural discontinuity and breakage, it is exactly the provisional and impermanent qualities of the periodical—its fluid, combinable and uncanonical makeup—that put it in a position to broker the piecing together of new cultural formations.”v While the texts of such little journals as Evreiskii Mir present a dizzying miscellany, the visual elements on the margins, down to the stationery letterhead, may guide us towards the editors’ grander designs.

.

DALIA WOLFSON is a graduate student in the Comparative Literature department of Harvard University. She studies modernist Hebrew and Yiddish prose of the early twentieth century.

iOn Evreiskii Mir and other projects in Russian-language publishing (such as the journal Safrut), see Kenneth Moss, Jewish Renaissance in the Russian Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 66–69.

iiEvreiskii Mir’s history, including Sobol’s extensive correspondence, is discussed in Vladimir Khazan, A Double Burden, A Double Cross (Boston, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2017), 55–67.

iiiOne evocative example of how such ceilings were perceived by modernist Jewish artists turning to folklore appears in El Lissitzky, “On the Mogilev Shul: Recollections,” trans. Madeleine Cohen, In geveb (July 2019).

ivBoris Khaimovich, “Leviathan: The Metamorphosis of a Medieval Image,” Images 1 (2020): 1–20.

vAlan Mintz, “Introduction: The Many Rather Than the One: On the Critical Study of Jewish Periodicals,” Prooftexts 15, no. 1 (1995): 1–4.