Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

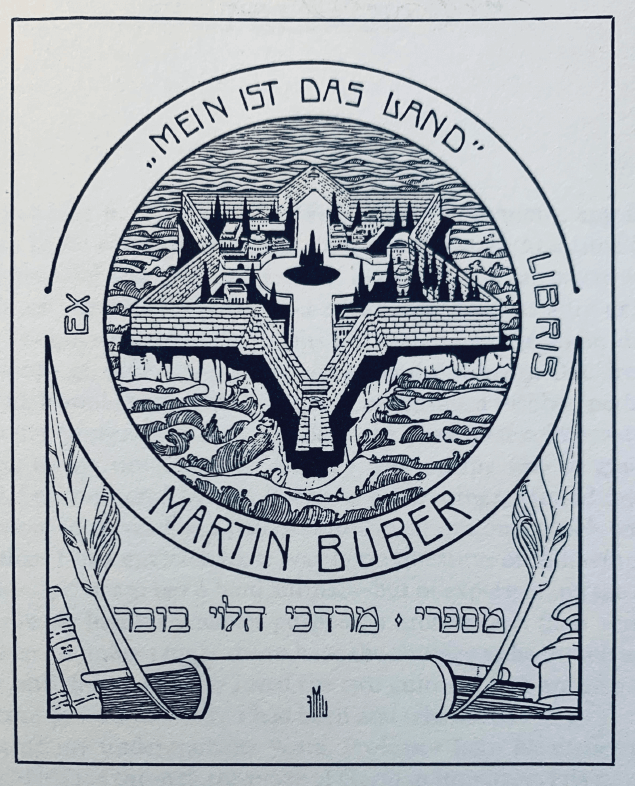

In 1901, the young Martin Buber addressed the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, where he claimed that modern Jewish art can be created only on “Jewish land” (‘adamah yehudit). That same year, he commissioned a bookplate featuring the phrase MEIN IST DAS LAND (The land is mine). To what land was Buber referring on these occasions? Did his words point to the territory of Israel, as dominant accounts of twentieth-century Israeli art would have it? Or did he use ‘adamah yehudit metaphorically, as the image of a garden city on the bookplate, which lacks any of the Holy Land’s attributes, suggests? In this short reflection on the meaning and historical import of Buber’s concept of ‘adamah yehudit, I put forward an answer to these questions.

Ephraim Moshe Lilien. Martin Buber Bookplate, 1901. The National Library of Israel, Ms. Var. 350 A/7a

Conventional art histories often claim that Buber’s 1901 speech founded the dominant paradigm for thinking about Israeli art, according to which modern Jewish art can only be made on Jewish land, that is, in Israel. Although the first mention of the speech in canonical work of art history only appears in 1980 in Binjamin Tammuz’s The Story of Art in Israel, this idea had been taken up as a key principle for understanding modern Jewish art in Israel by at least 1939, when Elias Newman published the first historiographical book on Israeli art, “Art in Palestine.” Obviously influenced by territorial Zionism, which took root among the Yishuv in this period, Newman’s text emphasizes the centrality of the territory of Israel for the development of modern Jewish art. However, Buber at no time belonged to this strand of Zionism. For Buber, Zionism was a cultural movement to be led by Jews all over the world, for the sake of all humankind. Although Buber’s statements were used to establish the territorial understanding of Israeli art, this was not Buber’s intention.

My reading of Buber’s concept of “Jewish land” stems from his well-known book On Zion: The History of an Idea (1944), in which he argues that there is a primordial universal connection between ‘adam (man) and ‘adamah (earth) with which God created and nourished him: and when man’s ‘adamah degenerates as a result of external circumstances, man himself declines with it. Although Buber uses this universal bond to explain the particular link between Jews and the Land of Israel, he does not see the territory as inherently holy. It is rather God’s choice of the Jewish people that is holy. This choice, though, must be continually reestablished. This will occur in the modern era, Buber explains, only when Jews fulfill their universal designation as role models for a new kind of human community.i In fact, On Zion articulates Buber’s fundamentally allegorical conception of ‘adamah, according to which it also stands for human social relations. Given that Buber’s early texts anticipate his later thought, I argue that his reference to “Jewish land” in 1901 did not exclusively point to Israeli territory and should be understood more broadly.

For Buber, renaissance is a manifestation of a developed kind of modern nationalism, which has shifted its focus from territory to culture.

This reading is bolstered by Buber’s essay “Jewish Renaissance,” which was published eleven months before the Basel address. It relates the concept of cultural rebirth—renaissance—to cultural Zionism. For Buber, renaissance is a manifestation of a developed kind of modern nationalism, which has shifted its focus from territory to culture. When Buber talks about culture, he refers to land rather than territory, hinting at its metaphorical linkage to cultural rebirth. Consider this passage: “Everywhere sleeping worlds emerge like green islands from the depth of the sea—within the soul of the individual human being, within the structure of societal reciprocity, in the artistic birth of works and values, in the external spheres of the cosmos, in the ultimate mysteries of all being—all things are renewed. Bathed in young light, the old earth sees with new eyes, and the rebirth celebrates its quiet sun festivals.”ii

Here, renaissance is understood as an internal and external rebirth of both the individual soul and cosmos, as manifested in cultural creation. Buber’s essay does not mention the Land of Israel at all, even in relation to the Jewish cultural renaissance. In fact, it is analogous with the bookplate, in which a Jewish island has risen from the sea—a metaphor for the Jewish community’s cultural rebirth. The metaphorical land presented in the bookplate’s image and text stands for the conditions under which Jews’ creative forces can unfold freely, wherever they reside.

This suggests that Buber’s 1901 address was part of a wider polemical debate over the essence of Zionism. Unlike political Zionism, Buber and his Democratic Faction party saw Zionism as Jewish cultural national movement. From this perspective, Zionism’s goal was to rebuild Jewish culture, not the Jewish state. Hence, when Buber explained that true Jewish art can be created only on Jewish land, he was actually allegorizing the concept of land. For Buber in this speech, ‘adamah yehudit is a well-defined and proud Jewish human community allowing Jewish cultural rebirth wherever that community is situated. Buber’s description of new Jewish literature, created throughout the Jewish Diaspora, best conveys the metaphor: “Nothing has brought to my attention as overwhelmingly as Jewish literature that a new land has been born, that we have received new strength and a new voice.”iii Clearly, the “new land” mentioned here does not refer exclusively to Israeli territory. Rather, it is understood as an empowered new Jewish community, as articulated in Jewish literature.

In this short intervention, I have argued that Buber’s “Jewish land” is best understood metaphorically. It stands for a new Jewish way of life, a cultural community in which the conditions are in place for Jewish creativity to prosper. For Buber, Jewish art can only flourish on Jewish land thus conceived, of which the Land of Israel is but one of many manifestations.

.

NOA AVRON BARAK is a Phd candidate in the Department of the Arts at Ben Gurion University of the Negev.

iShalom Ratzabi, Anarchy in “Zion”: Between Martin Buber and A. D. Gordon (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2011) [in Hebrew].

iiMartin Buber, “Jewish Renaissance,” in The First Buber; Youthful Zionist Writings of Martin Buber, ed. Gilya Gerda Schmidt (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 32. Author’s italics.

iiMartin Buber, “Address on Jewish Art,” in Schmidt, The First Buber, 59. Author’s italics.