Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

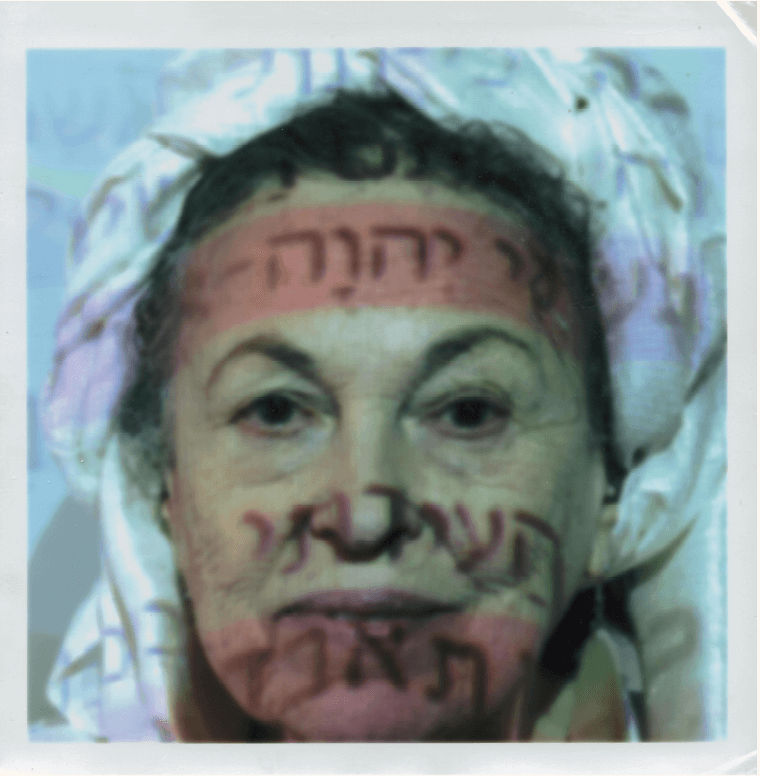

Fig. 1. Helène Aylon. Self Portrait: The Unmentionable, 2005. Color photograph.

Feminist thinkers have often challenged the transcendent male image of Providence in favor of a more immanently afeminine notion that embraces the world and human experience, rejecting any identification of vulnerability with weakness. The resultant alternative notion of divinity opens the way to a different, perhaps more harmonious relationship between humankind and the world. Self Portrait: The Unmentionable (2005; fig. 1) mounts Helène Aylon’s (1931–2020) struggle to write feminine divinity back into Judaism by superimposing the name of God onto her forehead. Observant Jews do not write or pronounce this name for God, because it is considered too sacred to be used in common parlance. The photograph was made by projecting Aylon’s Digital Liberation of G-d (2004) onto her face, therefore showing the holiest name of God (the letters yod-hei-vav-hei—YHVH) written in Hebrew across her forehead.ii

Fig. 2. Helène Aylon. The Liberation of G-d, 1990–96. Fifty-four altered versions of the five books of Moses, velvet panels, velvet-covered pedestals, lamps, magnifying lenses, video monitors. Installation view, The Jewish Museum, New York, 1996.

The Digital Liberation of G-d is a video version of Aylon’s groundbreaking installation The Liberation of G-d (1990–96; fig. 2), which was the first and central work in the series The G-d Project: Nine Houses without Women. This twenty-year project proposed a scathing feminist critique of Jewish texts and rituals. In the installation The Liberation of G-d, Aylon covered pages of the Hebrew Bible with transparent parchment and highlighted the verses that she found offensive to a feminist reader with a marker, questioning verses that express sexist and misogynistic views. She asks, “Do they belong in a holy book? Did God say it to Moses, or is it a patriarchal projection?” In this pioneering work, the artist purged the text of its sexist and misogynistic verses, as if to liberate God from the effects of patriarchy.

.

Fig. 3. Helène Aylon. My Notebooks , 2011 [1998]. Fifty-four Israeli school notebooks, masonite panel, velcro, and chalk on blackboard. Installation view, Mishkan LeOmanut, Museum of Art, Ein Harod, Israel, 2012.

Self Portrait: The Unmentionable connects the demand to restore the female side of God in the Jewish world, on the one hand, with the demand to bring back women themselves into Jewish history and to reclaim women’s spirituality, on the other. In this way, the work continues in a similar vein of another prominent work of the artist, My Notebooks (2011 [1998]; fig. 3), which further deals with the challenge mounted in The Liberation of G-d. An installation comprising fifty-four empty notebooks accompanied by text written in chalk on a blackboard, My Notebooks deals with exclusion and invisibility. In the chalk text, Aylon imagines a lost Torah, one that was never written or handed down to the Jewish people from their foremothers. She dedicated the installation to the women excluded from Jewish history: “To Mrs. Rashi and to Mrs. Maimonides, for surely they had something to say.”

In her important book After Christianity, the feminist theologian Daphne Hampson pointed out that the male God represents what is considered male perfection (power, singularity, etc.), and therefore monotheistic religions are a “feminist nightmare.” iii However, unlike Hampson—who called for women to leave the church and establish a post-Christian religion—Aylon’s intention is to create change from within her Jewish world.

Whereas most American Jewish feminist artists in the past did not foreground their Jewishness but emphasized their gender identification in a collective movement, Aylon’s engagement with a critical stance related to her Jewish identity since the 1990s constitutes a groundbreaking, radically social avant-garde, and sets itself a goal to effect changes in the Jewish world.

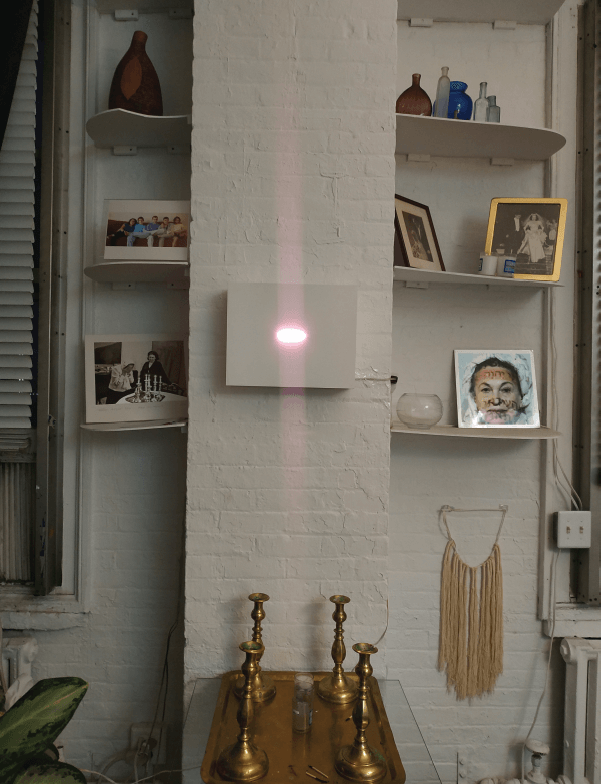

Fig. 4. David Sperber. Untitled, 2019. Color photograph.

Aylon died in New York of COVID-19 on April 6, 2020. During her final year of life, I had the pleasure and honor of being with her for many hours and even whole days in which I interviewed her and studied her archives. With her permission, I photographed one corner of her home, consisting of her Shabbat candles and a photograph of her and her mother lighting the candles (fig. 4). This corner also included pictures of her family, traditional Jewish ritual objects, and a tzitzit necklace—a ritual object she had invented and used in her performances in the distant past.

In the center she placed her work My Eternal Light: The Illuminated Pink Dash (2011), which she compared to the ner tamid (eternal flame) in the synagogue. “The ner-tamid,” Aylon told me, “completes my long-standing critical preoccupation with the exclusion of women from the Jewish world, and the call to bring them back into the discourse.” Aylon stated: “The pink dash is what’s missing. That’s what’s off-balance. How could we have a religion without women in it? We love our Jewish culture, but we have to analyze what from the culture includes women, what doesn’t. And what from the culture was indeed originated by women.”iv And on the right side of this work, she placed on the shelf Self Portrait: The Unmentionable.

.

DAVID SPERBER is an art historian, curator, and art critic. He is head of the Curatorial Studies Program at the Schechter Institutes, Jerusalem and member of the Israeli Rabbinical Studies Program at the Hebrew Union College, Jerusalem. Sperber’s book entitled Devoted Resistance: Jewish Feminist Art in the US and Israel was published in 2021 by the Hebrew University Magnes Press.

iThis article is based on my short essays published in The Female Side of God: Visual Representations of a Suppressed Tradition (Frankfurt: The Jewish Museum Frankfurt, 2020), 60–65, 234–64.

iiIn religious Jewish writing, the word “God” is written with a dash (G-d), to avoid writing the holy name of God.

iiiDaphne Hampson, After Christianity (London: SCM Press, 1996), 124.

ivJudy Batalion, “Helène Aylon in Conversation,” n. paradoxa 33 (2014): 64.