Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

Does the outer space into which we dissolve taste of us at all?

-Rainer Maria Rilke

Mid-century America: Marc Chagall’s prints were popular, Borscht Belt comedians were fixtures on TV shows, and architect Percival Goodman’s invitations for artists’ synagogue work coincided with Harry Belafonte joyously singing “Hava Nagillah.” Jewishness was being seamlessly mixed into the American soup.

Meanwhile, Jewish abstract expressionists, and there were many, were invited by the two major critics of the time— Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, also Jewish— to dissolve their Jewishness. Cautiously aware of Jewish self-exile, some artists fielded some subcutaneous pushback. Morris Louis had paintings named for the Hebrew alphabet (albeit posthumously) and Jules Olitski, late in life, titled paintings with biblical references.

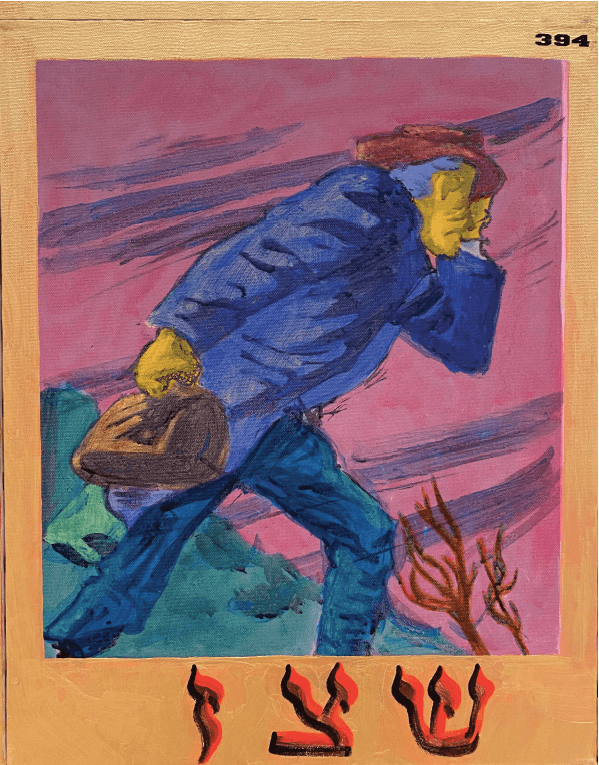

Archie Rand. 394: To Eat the Thanksgiving Sacrifice on the Day It Was Sacrificed (Leviticus 22:30), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas, 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

As a young painter I looked mostly towards Jackson Pollock and as an adolescent was fortunate, through art critic Clement Greenberg, to have met his contemporary Barnett Newman, a hero of mine. Although I never anticipated being regarded as a “Jewish” artist I didn’t shy away from it. A substantial chunk of the gallery scene, dealers and artists, was peopled with Jews and to the naked eye nothing seemed unusual about being a Jew in visual manufacture and commerce. I had shown a well-reviewed series of ten paintings in 1972 that were titled with the names of the ten rabbis of the Yom Kippur martyrology, which was unremarked in critical analysis. A commission in 1974 to mural the interior of Congregation B’nai Yosef, an Orthodox Brooklyn synagogue, opened the vastness of untapped potential that lay in Jewish literature, which could be used as armature for my studio work. With the exception of encouragement from older Jewish painters, notably Philip Guston and Jules Olitski, most of my peers reacted with open hostility to my working with “religious” subjects. I questioned why. These are some of my thoughts about the atmosphere that artists confront if they are working from any positioning derived from their experience as American Jews.

Barnett Newman named a number of paintings with biblically derived titles. In Newman’s The Stations of the Cross (the concept being a seventeenth-century Catholic invention that Protestants don’t employ), the abstracted narrative proposes assimilative conciliation although it at the same time gingerly conceals the subversive. The first two paintings of that series, from 1958, were initially called Adam and Eve. No matter how abstract his work could be, Newman always remembered that Jesus was Jewish. Sometimes Newman spoke to me in Yiddish, a great memory. I’ve heard the joke that art history is Jews explaining Catholicism to Protestants.

Where Newman’s paintings contained an unflinchingly located witness, Mark Rothko’s conceptions were amorphous and bloodless, beckoning an offstage theremin’s woo-ee-ooo. Desperate to goyishize divinity, Rothko lacked the cultural chops to get the specifics right. It’s a country club, Mark. They can smell your concealed passion, your smarmy intelligence. While Philip Guston looked to the torment of a camouflaged Babel riding with the Cossacks and succeeded eventually in being both Jewish and an artist, Rothko actually thought he was smart enough to pull off being perceived as ecumenical. I met Rothko. He was miserably disdainful of the second generation staining colorfield painters (read Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis—née Bernstein) whom he mistakenly believed co-opted his style and got credit for his stuff. Frankenthaler took inspiration from Jackson Pollock. Rothko, like Adolph Gottlieb, tried to develop a brand, a symbol, that would wow the viewer, hoping that his successful contribution to this utopian visual Esperanto would universally translate and finally give Jews some rest if not acceptance—or even applause. But Rothko’s pontifications, yes hubris, belie the authenticity of his product.

However, Rothko’s last black, austere, paintings, produced in fatigue, are uniquely magnificent. Rothko’s mid-canvas horizon line stretches to the ends of the support (which Guston would employ in the mid-1970s), making “land”— something Jews didn’t historically own. Chagall doesn’t have “land”—everyone floats—and the nineteenth-century Sephardic artist Camille Pissarro atomizes the world into a spray in his Impressionist paintings. That unatmospheric place in Rothko’s last black paintings could be inhabited but Rothko had no ability to live nontheoretically. Shocked, the somber luftmensch had unintentionally succeeded in painting an idol—a believable space. Rothko’s faith had been long discarded and strategically replaced by intellect, so he fell prey to this common tactical blunder. After working with Max Weber he had always made the smart move siding with seykhel over kishkes. Now Rothko found that he had painted a Jewish space, bereft of consolation, and had blocked himself from entrance to his own work. In the frenzy of his chronic disappointment he, unawares, had made a Golem, staring back, and he was afraid. Horrified, he had fabricated bleakly infinite polar midnights and they were real. They, finally, were Jewish paintings. Like Walter Benjamin, paralysis locked in the hills of Spain, Rothko died by suicide. My friend Philip Guston was later to warn, sternly, “To paint is a possessing rather than a picturing.”

Having a visual history verifies a culture as a respectable group.

Having a visual history verifies a culture as a respectable group. Museums dutifully mount heraldic banners of these cultures’ recognizable, national sophistication. Paintings and sculptures validate that there were individual, national distinguishing values and these displayed images are tangible acknowledgments belonging to and representing these Western fiefdoms: Italian, Spanish, Dutch, German, American, Romantic, Renaissance, Constructivist, Impressionist, etc. If you have no visual history then you have to make one in order to get a seat at the table. And that’s what Jews need(ed) to do. Otherwise you don’t exist.

Over time, marginalized groups can sense the plates shift underfoot, leaving fresh opportunity for the entrance of their unenlisted voices. This rush to claim curatorial viability is in full swing as the disenfranchised address the challenge for a reconstitution of a visual history, providing a foundation for alternate aesthetics and acceptances.

But for many reasons, Jewish self-portrayal in artistic culture remains self-contained and hermetically coherent to itself without invitation or reflex to meld into the host cultures’ visual component. That’s because if Jewishly inflected art is acknowledged then Jews must be considered a “nation,” a “people,” separating their communal and behavioral identities from the sole connotation of their being religionists. Jewish art and its reception is a topic on which I could write pages but it would not be acceptable to a vast majority of people. As recently as April 2021, the New York Times, supported by Wikipedia, outrageously referred to Isaac Bashevis Singer as a “Polish” writer, only incidentally, and later referred to his being a Jew. As Jewish artists, our insistence on self-identification will gain us no advantages. It is a moral choice about whose outcomes I harbor little optimism.

.

ARCHIE RAND, Presidential Professor of Art at Brooklyn College, is the subject of more than 300 solo and group shows. His work can be found in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Institute of Chicago, and Bibliothèque Nationale de France, among many others.