Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

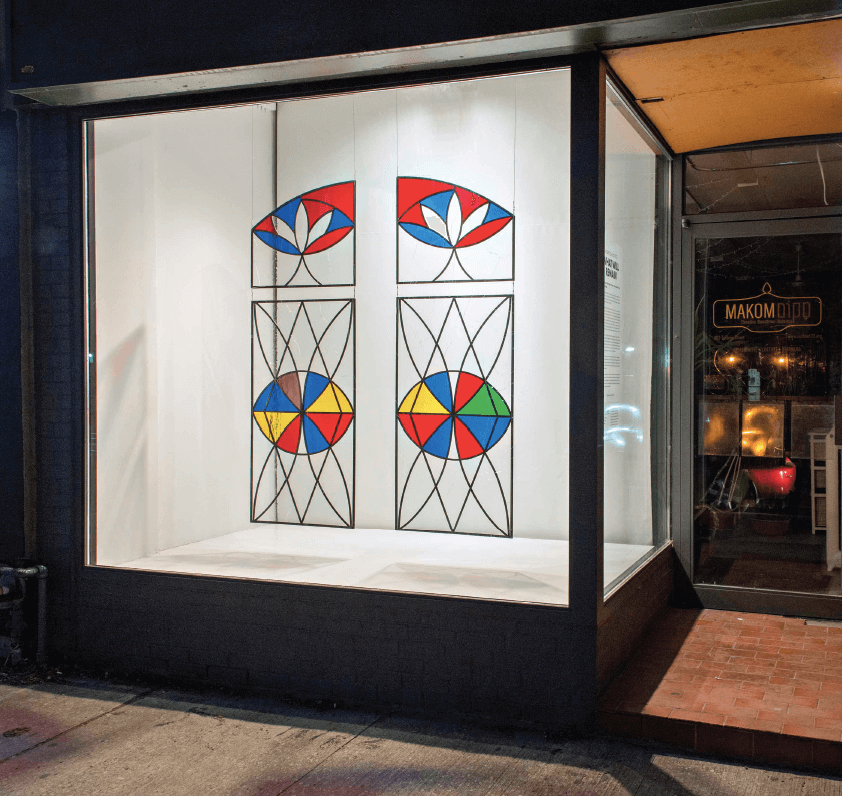

Robert Davidovitz. What Will Remain, 2020. Site-specific installation at FENTSTER. Photo by Morris Lum

Toronto artist Robert Davidovitz’s trademark woven paintings explore dynamic palettes and the materiality of paint. In a new work created for the FENTSTER window gallery in downtown Toronto, entitled What Will Remain, he extends his study of color and form to the medium of glass, embracing a material central to his family’s endurance through various stages of upheaval, beginning with his grandfather, Motel, born in Vilna in 1912. Against the backdrop of honouring his patrilineal line, Davidovitz’s installation equally references important father figures of Jewish thought and culture, all with connections to Vilna, including the influential eighteenth-century rabbi known as the Vilna Gaon, eminent artist Marc Chagall, and prominent Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever. Together their stories and work inform this contemporary sculpture, which was made and exhibited at the start of the global pandemic in spring 2020.

Recuperating a connection to his ancestral roots in Vilna offered Davidovitz an entry point to creating a site-specific piece for FENTSTER,i a Jewish exhibition space located in a storefront window in Toronto’s early Jewish immigrant neighborhood. The artist’s grandparents escaped the extermination of Vilna’s Jews by fleeing to Uzbekistan in 1941. After the war, they returned to a ruined city. Motel repaired broken windows to support his young family. When his son (the artist’s father) Meir made aliyah in 1973, he in turn opened a window business, often restoring synagogue stained glass. The Davidovitz family moved to Canada when Robert was seven and windows were again their entrée into a new life.

In his father’s workshop, Davidovitz created this installation as an homage to Vilna and to the delicate material that buttressed his family for generations. Before the Second World War, Vilna (present-day Vilnius) was an important center of Jewish life, known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, a dynamic hub of Jewish learning, culture, and diverse ideological movements. Davidovitz’s glass hanging is inspired by a 1935 painting Chagall made of the kloyz of the Vilna Gaon, who was a figurehead of the rationalist Mitnagdim movement, countering the rise of Hasidism’s mystical views. Chagall visited Vilna to attend a scholarly conference at the YIVO Institute,ii the center for the study of Yiddish language and culture. Known as the capital of Yiddishland, in the interwar years Vilna was a hub of modern Yiddish culture and innovative Jewish life and arts—home to Yung Vilne—a group of young Yiddish writers and poets that included Avrom Sutzkever. Davidovitz’s project was named for a phrase from a celebrated Sutzkever poem that repeatedly asks: “Who will remain? What will remain?”iii

Through his stained-glass sculpture, Davidovitz harkens to a onetime Vilna landmark, reinterpreting the colorful windows of Chagall’s canvas of the synagogue that was later destroyed during the war. He considered Chagall’s picture closely alongside archival photos to determine how to fashion the windows. Intertwining personal and collective memory and working in an empty warehouse during the first lockdown, Davidovitz engaged in a quiet dialogue across time with these voices from Vilna, including a grandfather he never knew.

Davidovitz “completed” the work by breaking it—giving his methodical process over to uncertainty. The cracked panes are a reminder of the centrality of brokenness in life, undeniable at a time when our daily existence has felt shattered on a global scale not seen since the Second World War. While associations to Kristallnacht are unavoidable, his is a generative gesture, not one of violent destruction. Fittingly, the work is ruptured, scarred, and imperfect but remains intact. The piece maintains its integrity despite the fissures. Brokenness is prevalent in Jewish tradition, from breaking the middle matzah at the seder,iv to Moses smashing the tablets, to the notion of tikkun ‘olam, repairing the world. Much like how a reminder of fragility and destruction interrupts the joyousness of a Jewish wedding when a glass is ceremonially broken, Davidovitz introduces fracture into the celebratory act of revitalizing a lost object from the past. This gesture is quintessentially Jewish. The sculpture also references how the work of repair has been essential to the subsistence of the artist’s family.

The exhibition title borrows Sutzkever’s lasting words without punctuation, vacillating between question and declaration. Passersby in Toronto gazed upon the window in a window over many uncertain and frightening months wondering—What will remain of life before? What will remain of this devastation?—and simultaneously confirming: What will remain is memory. What will remain is tradition. Connection and love will remain. Art and nature will remain. To conclude as Sutzkever did: “Is this not enough for you?”

Photo by Avia Moore

EVELYN TAUBEN is a Montreal-born, Toronto-based producer, curator and writer. She is a leader in the field of contemporary Jewish arts and culture, founding and curating FENTSTER – a window gallery that explores the Jewish experience through contemporary art.

iFentster is the Yiddish word for “window.” The artist-run gallery is located in the storefront window of the hub for the independent Jewish community Makom: Creative Downtown Judaism.

iiBenjamin Harshav, “Chagall, Marc,” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, December 15, 2010, https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Chagall_Marc.

iiiAvrom Sutzkever, “Lid fun a togbukh / Poem from a Diary,” 1974.

ivWith thanks to Rabbi Jenni S. Friedman for noting this aspect of breaking in Jewish tradition.