Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

In 1909, fourteen-year-old Alice Pentlarge’s family spent several spring and summer months in Europe on their version of the Grand Tour. Every place they went—London, Frankfurt, Prague, Amsterdam, Berlin, Rome—Alice’s mother took her to visit synagogues and Jewish quarters. Similarly, Clara Lowenburg Moses attended synagogue on Yom Kippur in Belfast during a 1912 trip, and Rebecca Hourwich Reyher headed to Rosh Hashanah services within hours of landing in Cape Town in 1924. None of these women made a habit of going to synagogues as part of their regular routines at home, even on the high holidays, but, like so many other Jewish travelers, while they were abroad they sought out more connection with the international Jewish community. Such activities could fall into the realm of a sort of cultural imperialism, an inspection of Jewish life in other lands, but they were also a natural expression of religious affiliation, though not necessarily observance, for tourists who were interested in visiting Jewish spaces even if they did not do so as part of their everyday lives.

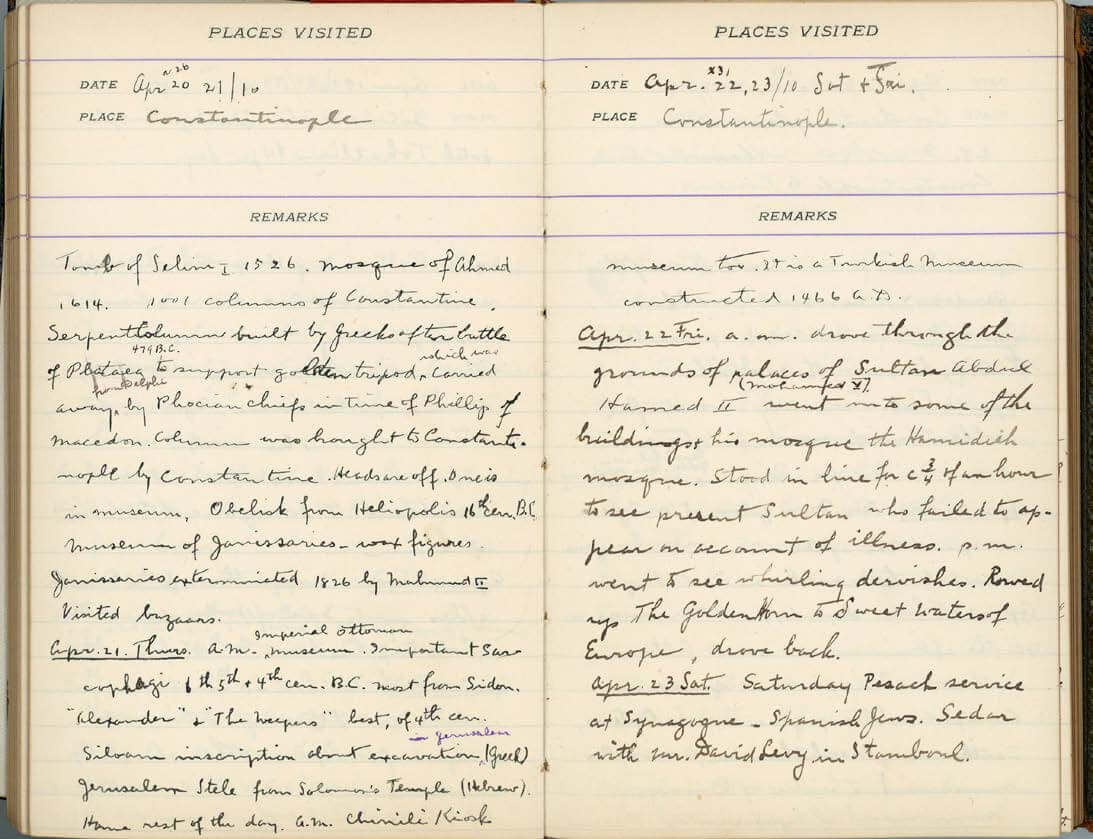

Pages from Ella Davis’s 1910 travel diary mentioning both sightseeing and a Passover seder. Davis and Isaacs Family Papers, P-936, at the Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center at New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Overtly religious or ethnic spaces abroad, whether synagogues or historically Jewish neighborhoods, provided travelers a point of connection to a larger—in these cases, international—sense of Jewish community. What we might now refer to as “doing Jewish” while abroad will seem familiar to the many modern Jewish travelers who engage in similar activities today. Its long history is evident in the diaries, letters, memoirs, scrapbooks, and photographs I am exploring as part of the research for my current book project on American Jewish women travelers during the decades between the Civil War and World War II.

Starting in the late 1800s, travel abroad became more accessible due to a new commercialization of tourism that targeted the middle class as well as the wealthy. An entirely new industry sprang up to serve adventurous but not necessarily well-to-do travelers, a mass of people who depended on affordable accommodations, transportation, guidebooks, maps, and markers to ease their journeys along increasingly well-trodden paths of sightseeing. These developments meant that a greater number of Americans visited foreign countries and interacted with people in other places. In an era of migration, travel as another form of international movement played a role in processes of modernization that helped shape American society and culture. Exploring the travel experiences of American Jewish women illustrates these broader trends while also attending to the particular transnational identity that led Jewish women to identify with each other across national boundaries.

While such travel was still beyond the means of most working-class people, the experience of going abroad became quite common for American Jewish girls and women during the late 1800s and early 1900s, and not only those from the most privileged backgrounds. They went to school overseas; visited relatives and hometowns; worked abroad; attended international meetings of various activist groups; and took sightseeing trips alone, with family members or friends, or with organized tour groups. Most went to Europe, but some visited Latin America, Asia, and Africa as well. Unsurprisingly, considerations of Jewish identity and affiliation were particularly salient for those who visited mandatory Palestine.

Travel endowed American Jewish women with a sophistication that enhanced their status within the Jewish community as well as within a larger community of women. Since domesticity was traditionally central to them as both women and Jews, especially if they were middle or upper class, the question arose of what happened when they left their traditional bailiwicks of home. While travel often challenged women’s conventional gender roles by expanding their agency and autonomy once they were freed from routine domestic duties, for Jewish women travel generally strengthened rather than diminished Jewish identity. Even those who rejected ritual observance or resisted social, cultural, and economic limitations rooted in their Jewishness discovered that once abroad, they identified as Jews as never before. They found themselves not only attending synagogue services but also marking Jewish holidays, socializing with other Jews, and visiting Jewish homelands, memorials, and cemeteries. Upon their return, they often gave new thought as to how to create homes that could offer a synthesis of domesticity, cosmopolitanism, and American Jewish identity. Constructions of gender were thus fundamental elements of their travel experiences.

So, too, were unsettling encounters with antisemitism, another factor in American Jewish women travelers’ decisions to spend some of their time abroad in Jewish spaces. During her long 1924 voyage to South Africa, Rebecca Hourwich Reyher heard multiple antisemitic remarks from both crew members and fellow passengers, none of whom realized she was Jewish. After enduring more than a week of such comments, Rebecca finally took great pleasure in informing her shipmates that she herself was Jewish, leaving them stammering in embarrassment. This was the context for her decision to attend Rosh Hashanah services when she arrived in Cape Town, something she had not done since early childhood. Experiencing antisemitism in such a personal way while traveling ultimately had the effect of heightening her sense of Jewish identity. American Jewish women travelers like Rebecca were well placed to take note of—and report on once home—the endemic antisemitism they found in many places and the contrast it presented with their lives in the United States. They became conduits for information about the status and treatment of Jews in other parts of the world.

For several generations of American Jewish women, travel experiences sparked novel ways of thinking about themselves as Americans, women, and as Jews, as well as new ideas about Jewish community rooted in religion, ethnicity, and heritage. Travel could both destabilize and reaffirm their religious, cultural, ethnic, national, and gender identities in ways that bear further exploration and speak to contemporary notions of intersectionality.

Melissa R. Klapper is professor of History and director of Women’s & Gender Studies at Rowan University. Her two most recent books are Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace: American Jewish Women’s Activism, 1890-1940 (New York University Press, 2013), which won the National Jewish Book Award in Women’s Studies, and Ballet Class: An American History (Oxford University Press, 2020).