Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

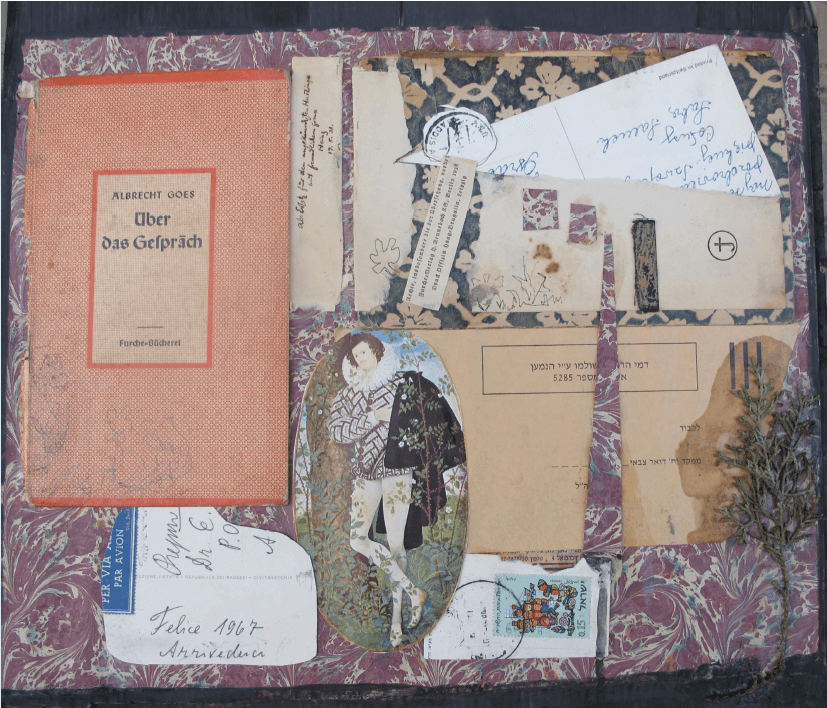

Heddy Breuer Abramowitz. About the Conversation, 2017. Mixed media collage. 11.75 in. x 14 in.

The amorphous question of what is Jewish identity has creeped onto center stage as I mature. The technological gallop became the backdrop for this exploration. I have witnessed the purging of libraries, the culling of reference books, the digitization of contents and its corollary: disappearing means of communication. This has resulted in rippling changes in the publishing world and perhaps other backwash continues. I am anxious about leaving literary legacies to administrators and efficiency managers. Whose culture will remain on the shelves fully intact? Which of many “narratives” will be prioritized and at the expense of which others? In light of au courant rhetoric and action, I feel it is ever more critical that the range of expression of Jewish identity be preserved.

From my father, who had witnessed Nazi book burnings and mourned the destruction of German cultural treasures and censorship, I learned early to value books.

To investigate these themes, I create collages using discarded book parts, vintage postcards, and cursive handwriting that for me represent a disappearing literary culture. I explore the individual’s relationship to writing, reading, and correspondence. These elements may evoke associations with specific times or places, add historic context, educe an author’s oeuvre, and, perhaps, jiggle the memory of the correspondents. Pulling together these now-quaint elements gives perspective on the passing of time; the slipping away of what were once familiar and mundane and their replacement by cutting-edge means. Cursive writing and—dare I say—penmanship are going the way of the buggy whip. The references to landmark touchstones of modern Jewish history are fading from collective memory. Here, these items compose a Zeitgeist in microcosm.

My collage About the Conversation is titled after the book cover of the same name by Albrecht Goes (1908–2000). It was exhibited in Authenticity and Identification, curated by Ori Z. Soltes this spring in Washington, DC. Placed on hand-marbled endpaper, a postcard from 1967 Addis Ababa (year of the Six Day War) is broken into a house structure with gardens, juxtaposed with what seems to be a renaissance-era dandy, and placed on an Israeli envelope of the pre-digital-age call-up notice to reserve service. There is a 1938 (year of the Anschluss that subsumed Austria into Nazi Germany) scrap in German cursive signed by a man named Heinz. The postage stamps of Ethiopia, Israel, and the cypress tree twig are meant to interact with the Goes book from the 1950s airing the subject of reconciliation of Germans and Jews a mere few years after the Shoah.

This work combines competing elements of my background: I was raised secularly in a southern Maryland suburb where I went to public school, a Jesuit college, and then law school at the state university. My family attended small Conservative congregations and my formal Jewish education was minimal. My home life as the daughter of survivors—of life in Nazi Austria and in Hungary; of concentration, extermination, and displaced persons camps; and of the experiences of a Buchenwald liberator with the US Army—gave me a prism through which I still see life. In my 20s, Israel became my home and my informal Jewish education picked up after formal structures ended.

From my father, who had witnessed Nazi book burnings and mourned the destruction of German cultural treasures and censorship, I learned early to value books. I cherished books as a public resource. Initially, I hesitated to transgress and “mutilate” a book. Yet, my finds were one step from the refuse bin. After a book’s first life was over, I reasoned, using it in my collages would repurpose the work and extend its place in contemporary culture.

I found the Goes book on one of the many hefker benches where people set out ephemera they aren’t prepared just to trash. This one was next to Jerusalem’s Gan Rechavia complex where many professors from the Hebrew University reside. The booklet was clearly vintage, and printed in German in a Gothic typeset. It joined the rest of my gleanings.

Preparing a collage for me is trial and error. I work intuitively and combine elements with the visual and the thematic elements in play from the beginning. In this work, I chose the central figure of the man standing in the garden because I noticed that his pose of hand-on-heart sincerity contrasts with his gaze. It struck me as aloof, that of a detached observer and perhaps emotionally distant. The subject could be an everyman of any era. Who is to say whether or not the figure is Jewish or whether he is in the position of the assimilated Jew of his time? He follows the fashion convention of his time; he is the one who blends. Perhaps his clothing presents one identity to the outside while covering his core identity on the inside?

I picked this painting by Nicholas Hillyarde (1547–1619) from an abandoned book of Elizabethan miniatures. It certainly had no Jewish associations at its inception; it spoke to me for that reason. The various elements in this collage are meant to reverberate against each other and be considered as clues to unasked questions. In the larger conversation about Jewish identity, who are we, where is home, and how do we view ourselves?

.

Photo by Michael Zerivitz

HEDDY BREUER ABRAMOWITZ is an American-Israeli multidisciplinary artist. Born in Brooklyn, NY to Holocaust survivors, she was raised in southern Maryland near Washington, DC. She is a painter, collagist, photographer and writer. Website: www.heddyabramowitz.com