Above: Tintype photograph by Will Wilson. Adam W. McKinney stands as Mr. Fred Rouse in front of the former Ku Klux Klan Klavern No. 101 Auditorium

IN/JUSTICE IN HISTORY

From 1939 to 1962 Felix Frankfurter held the “Jewish seat” on the US Supreme Court. Justices do not “represent” constituencies, but presidents often chose them for geographic, religious, racial, gender, ethnic, and cultural balance. Unfortunately, Frankfurter refused to offer such balance, and in some critical instances harmed Jews and other minorities. When he retired, after a stroke, he was annoyed that President John F. Kennedy appointed his secretary of labor, Arthur Goldberg, to replace him, because, as his most recent biographer notes, “Frankfurter abhorred the idea of a Jewish seat” on the court.i

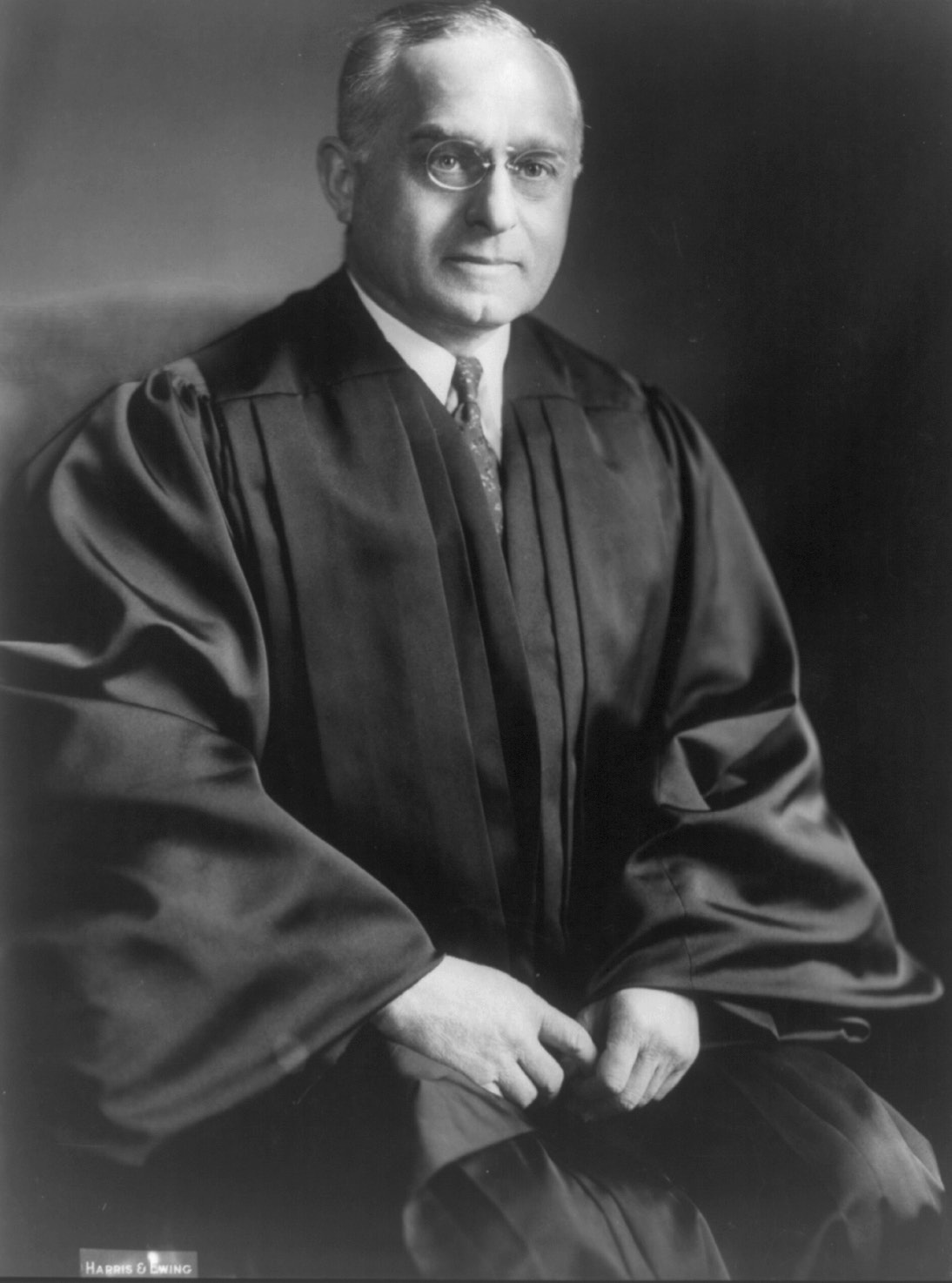

Felix Frankfurter, Supreme Court justice portrait., November 1958. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-134429

A brilliant activist lawyer, Frankfurter worked in the Wilson administration, was the first tenured Jewish professor at Harvard Law School, and was a close advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt. He worked with Louis Brandeis in the Zionist movement, visited the Yishuv after World War I, and as a sitting justice lobbied President Harry Truman, cabinet members, and the State Department to pressure Britain to increase Jewish immigration to British Palestine and for the United States to support partition to create a Jewish state, and then formally recognize Israel. This lobbying was mostly done through one of his many Jewish protégés, David Niles, who worked in the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. Indeed, throughout his career, Frankfurter was the patron of many young Jewish lawyers. In an age when antisemitism blocked Jews from access to prestigious law firm jobs, Frankfurter guided many to government service, teaching positions at elite law schools, and eventually federal judgeships. While an advocate for Jews, he eschewed Judaism, marrying the daughter of a Protestant minister at a time when intermarriage was rare for immigrant Jews. His mother refused to attend their civil ceremony. He stopped attending any synagogue at the age of fifteen, but arranged for one of his former students who had attended a yeshiva as a child to say Kaddish at a memorial service in his Washington, DC, apartment, before he was buried in a Protestant cemetery in Cambridge.

Frankfurter. . . supported sending completely innocent [Japanese] American citizens . . . to concentration camps because of their ethnicity, and later went out of his way to justify [Sunday closing] laws that blatantly discriminated against Jews.

While Frankfurter advocated for a Jewish homeland for the survivors of the Shoah, his response to the Holocaust itself was problematic. Before he was on the court, Frankfurter urged the administration to stand up to Hitler and increase immigration (which given the mindset of Congress was a lost cause). But, while on the court, he turned a blind eye to the Holocaust, refusing to use his considerable influence to push for whatever rescue might have been possible. In 1943 Jan Karski, a Polish resistance fighter, briefed Frankfurter on the Warsaw Ghetto and the Belzec death camp (which he had infiltrated). Saying, “I do not believe you,” Frankfurter refused to take this information to Roosevelt. It is not clear what the United States could have done to stop the Nazi genocide in 1943, other than quickly winning the war, but ignoring evidence of the Final Solution was hardly useful.

On the court, Frankfurter weirdly used his Judaism to defend the oppression of another religious minority, supported sending completely innocent American citizens, including the elderly and children, to concentration camps because of their ethnicity, and later went out of his way to justify laws that blatantly discriminated against Jews.

Frankfurter’s majority opinion in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940) upheld the expulsion of Jehovah’s Witness elementary students who refused to salute the American flag because they believed this was the equivalent of idol worship. American Witnesses had stopped saluting the flag in solidarity with German Witnesses, who were sent to concentration camps for refusing to salute the Nazi flag. While Frankfurter’s own uncle was incarcerated in Vienna for being Jewish, Frankfurter justified the persecution of members of a minority faith in the United States on the grounds that forcing children to violate their religion (and expelling them when they did not) would instill patriotism in them. Although not his intention, Frankfurter’s decision led to increased discrimination against Witnesses and violent vigilante attacks on them across the nation. In West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Court reversed Gobitis, as a number of justices who had supported Frankfurter now acknowledged their error. Justice Robert Jackson (who would later be the chief US prosecutor at Nuremberg) wrote a brilliantly eloquent opinion defending minority rights and free speech. Stubbornly dissenting, and thus continuing to be an advocate for religious discrimination in the face of ongoing violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses, Frankfurter used his Jewish heritage to justify legal persecution of Witnesses, writing, “One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution.” Asserting that “as judges we are neither Jew nor Gentile, neither Catholic nor agnostic,” he then argued such freedoms did not apply to schoolchildren.ii This use of his Jewish heritage, while Jews were being massacred by the Germans, is shocking.

A year later, in Korematsu v. United States (1944), Frankfurter wrote to support incarcerating 120,000 Japanese Americans, mostly US citizens, in remote and desolate camps surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers. Justice Jackson, who wrote the majority opinion in Barnette, vigorously dissented against the racism in Korematsu. Similarly, Justice Owen Roberts dissented, asserting this was a “case of convicting a citizen as a punishment for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition towards the United States.” The Jewish justice did not blink at supporting such “imprisonment in a concentration camp.” While not directly affecting Jews, these cases illustrate Frankfurter’s blindness to the irony of his own position and racial and religious persecution in his own country.

In the face of ongoing violence against Jehovah’s Witnesses, Frankfurter used his Jewish heritage to justify legal persecution of Witnesses, writing, “One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution.”

In 1961 the court upheld Sunday closing laws, which as their name implies, prevented most businesses from operating on the Christian Sabbath. In one case, Abraham Braunfeld asserted he would “be unable to continue in his [retail] business if he may not stay open on Sunday,” because as an observant Jew he could not work on Saturday. Frankfurter had no sympathy for Braunfeld. The Roman Catholic Justice William J. Brennan dissented, noting that the “effect” of such laws “is that no one may at once and the same time be an Orthodox Jew and compete effectively with his Sunday-observing fellow tradesmen.” Brennan argued “this state-imposed burden on Orthodox Judaism” was unconstitutional.

A companion case involved Crown Kosher Supermarket, which Massachusetts authorities fined for opening on Sunday. This case was perhaps more compelling than Braunfeld’s, who could plausibly have hired non-Jews to run his store on Saturday or taken a non-Jewish partner to do so. But that was impossible for Crown Kosher. If it were open on Saturday, it would no longer be “kosher.” Furthermore, if Crown Kosher was closed all weekend, its observant Jewish customers with a traditional Monday to Friday work week would have great difficulty shopping for food.

Not content to merely agree with the majority opinion upholding these laws, Frankfurter wrote a massive eighty-four-page concurrence followed by eighteen pages of appendices to defend his support for a law titled “Observance of the Lord’s Day,” making the Christian Sabbath an “official” holiday, while irreparably harming many Jews. The Catholic Brennan and the Protestants Potter Stewart and William O. Douglas defended the rights of Jews. Frankfurter was over the top supporting their persecution.

So, what can we make of Frankfurter? Born Jewish, never denying his heritage, and constantly helping young Jewish lawyers, as a justice he seemed to go out of his way to distance himself from the legitimate needs of American Jews. During World War II he supported the persecution of American religious and ethnic minorities, even while the nation was fighting Nazi racism and persecution. The only time he invoked his “Jewishness” from the bench was to justify expelling young schoolchildren who refused to violate their religion, while Nazis were murdering Jews in Europe. How do we explain this? One answer may be that for all his work behind the scenes as a Zionist, he was never comfortable with his status as an immigrant and a minority, and consciously tried to prove that he was not “really” Jewish. Alternatively, as someone who rejected any sense of faith or religious belief, he simply had no sympathy for Jews who would not work on Shabbat or Jehovah’s Witnesses who would not salute the flag. His support of the Japanese internment—again while Jews were behind barbed wire in Germany—may again suggest his deep need to be mindlessly patriotic to prove he was really an American. The powerful dissent in Korematsu by the Protestant Justice Jackson (two years before he would lead the prosecution at Nuremberg) stands in contrast to Frankfurter’s support for the internment.

PAUL FINKELMAN is Rydell Visiting Professor at Gustavus Adolphus College and research associate in the Max and Tessie Zelikovitz Centre for Jewish Studies at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. Among his many publications, his most recent major book, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court, was published by Harvard University Press in 2018.

i Brad Synder, Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment (New York: W. W. Norton, 2022), 709.

ii Here he is ironically paraphrasing Paul’s letter to the Galatians (3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”) Given Frankfurter’s incredible education (and the fact that he studied classics at City College of New York), it is not unreasonable to assume that this was deliberate.