Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

PEDAGOGY

Lexical Note: Pedagogy, deriving from the Greek meaning “lead/bring along a child,” naturally correlates with travel because both involve movement. Travel derives from the French travail “work, labor, arduous journey,” from the Latin tripaliare, “to torture.” Along with the Hebrew n-s-ʿ “travel by stations,” the Latin and French trajectory of the term suggest dimensions of the travel-study course.

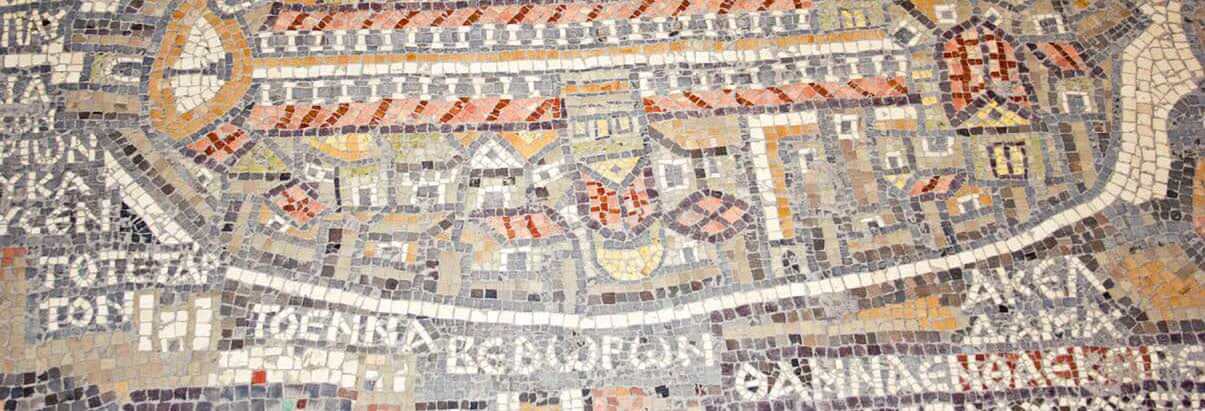

Mosaic map of sixth century Jerusalem found under the floor of St George's Church in Madaba, Jordan. Photo by David Bjorgen, via Wikimedia Commons

Since resources abound on the pedagogical value of travel and the detailed processes required for preparing and conducting a travel-study course, I offer here some reflections on guiding principles for a couple of travel- study courses that might be of interest. Designed for undergraduates, “Antiquity and Modernity in Israel and Jordan,” consisted of a 3.5-week journey through Israel and Jordan. “Healing in Antiquity” was a semester course punctuated by a ten-day spring-break trip to Greece. While such courses involve a number of administrative minutiae which can overwhelm their pedagogical value, I followed principles that integrated both academic content and travel practices: utilize travel as a tool for thinking about subjects differently; provide an overarching frame of reference for processing daily experiences; teach students how to travel on their own; respect the stories that dwell in these places; differentiate between travel and tourism.

It was quite a journey to bring a group of students outside the Memorial Church of Moses to discuss rabbinic midrash on Moses’s death in dialogue with Rachel Bluwstein’s poem “Mi-neged” on Mt. Nebo in Madaba, Jordan, with its panoramic view of the

Jordan Valley (“in every expectation there is a Mt. Nebo”). The journey began with a colleague in Philosophy describing an undergraduate travel-study course that consisted of analyzing writings of various philosophers at sites scattered throughout Greece. The colleague acknowledged that the technique bordered on cheesiness, but it effectively stimulated student engagement and generated enduring understandings. This encounter germinated ideas for the two travel-study courses that were the most rewarding and labor-intensive teaching experiences that I have had. In addition to heeding the common advice about such courses—the need for advance preparation and institutional support both financially and administratively (UC International was fantastic and 100% necessary)—intentional principles maximized the educational value of these courses.

Even with a syllabus as a map, the ancient is awkward and bewildering.

Utilize travel as a tool for thinking about subjects differently. Beyond the revelatory impact of encountering the Other and Otherness, the Israel-Jordan trip required students, like the Nabateans or inhabitants of the Decapolis, to think about the area horizontally rather than vertically through a west/east instead of the typical north/south orientation. Visiting ancient healing centers dedicated to Asclepius at Epidaurus and Kos initiated conversations about the impact of the location, space, and design of contemporary medical institutions and their environs on the healing process. Providing an overarching frame of reference for processing daily experiences actualizes this principle. Students in both courses took turns blogging daily about how they experienced the interaction between antiquity and modernity. This included connecting the international orientation of the Nabateans to the variety of foreign tourists at Petra or reflecting on a visit to the Garden of Hippocrates, where director Julie Zafeiratou combined Hippocretean and Galenic healing traditions with Greek mythology, feminism, environmentalism, and refugee relief.

The frame of reference, however, functions as a map, not an itinerary, thereby supporting a primary goal of the courses, teaching students how to travel. Hence the recommendation to differentiate between travel and tourism. This means balancing visiting major tourist sites with places that students would be less likely to visit on their own, such as stopping at Wahat-al-Salaam/Neve Shalom and Netanya Academic College or pausing at the Holocaust Memorial next to the Kerameikon, the ancient cemetery of Athens. Once, time constraints required us to choose between touring the National Archaeological Museum and the anarchist neighborhood of Exarchia adjacent to the museum. Following our guide’s recommendation, a PhD in Bronze Age archaeology and resident of the neighborhood, we traveled the less-toured path and encountered the stories and richly graffitied urban landscape of Exarchia. Our guide reasoned that this would have a far more transformative impact and the students would go to the museum when next in Athens.

Moreover, since we had already encountered numerous archaeological sites and artifacts, we needed a balanced embodiment of the principle that travel should involve respecting and honoring stories that dwell in these places. Besides listening to these stories, we told them as well. For the Greece trip, students had to present at a site on a relevant ancient topic generally not related to healing, such as the features of a Greek theater (Epidaurus), Socrates (Athenian Agora), Demeter (Eleusis), or ancient ships (Kos). Prior familiarity prepared beforehand enhances independent and respectful travel. In fact, even mundane administrative procedures can be opportunities for training students to travel on their own: interviews of prospective participants offer the chance to impress the importance of flexibility and students learn about additional required pretrip preparations related to passports, securing transportation and lodging, and mastering a few common phrases in local languages. I also gradually introduce opportunities for students to individualize their experiences and create their own stories as they become more comfortable acting independently.

Reflecting on the likelihood of travel-study courses at this moment uneasily reminds me of what one student blogged: “Mt. Nebo—seeing the promised, better future spread before you, but knowing you will not be able to have it.” Yet the profound pedagogical value of travel points to its possibility through a productive metaphor of pedagogy as travel. After all, thinking differently, frames of reference, maps=syllabi=stations, and teaching how to learn are staples of quality instruction. Working primarily in antiquity, I find that students, as if visiting a new place with a new language, either think about the subject differently from their immersed instructor, or, more commonly, are thinking about it for the first time. Even with a syllabus as a map, the ancient is awkward and bewildering. I suspect this would be true for any number of fields. For this reason, the principles for travel study apply to teaching in general, especially training to travel on one’s own. Students independently revisiting a subject, absorbing related yet unexplored content by themselves, and applying the experiences from their curricular travels when they visit new subjects and materials would be a true measure of pedagogical success. We continue to have, and always have had, the opportunity to guide students on journeys.

Matthew Kraus is associate professor and head of the Department of Judaic Studies at the University of Cincinnati. Among other publications, he is most recently the author of “Christian Translation in Late Antiquity,” Routledge Handbook of Translation History, Christopher R. Rundle, ed., (London: Routledge, 2021) and “Letter 49,” American Values, Religious Voices, March 9, 2021.