Teaching a Bible class typically involves disrupting my students’ preconceptions—illuminating historical context, complicating the composition of stories and manuscripts, and interjecting ancient meaning obscured by time and translation. With such focus on uncovering the Bible’s original context with a scholarly lens, I devised an end-of-semester assignment that would allow for my students’ own textual experimentation.

Inspired by Sarit Kattan Gribetz’s AJR article on creative pedagogy, I instructed my students to select a biblical passage. They then completed an assignment in three parts, spaced out over the semester:

The students first conducted exegesis of their passage, analyzing vocabulary, historical context, and relevant modern scholarship. Then they traced their passage to its modern reception, compiling a list of articles, youtube videos, memes and even bumper stickers so as to analyze the range of interpretations in the modern setting. The final part of the assignment invited students to interpret their biblical text in a creative mode of their choosing. A creator’s statement accompanied each creation explaining their interpretive choices.

During the final class, I transformed our classroom into a gallery—hanging their art, printing their poems, and screening recordings on the projector. We gathered and mingled and admired the intimacy of interpretation. The biblical text prompted a range of responses. One particularly dry-humored student reimagined the four beasts in Daniel 7 as members of a modern-day support group, crafting a screenplay in which the beasts grapple with the publics’ fear of their monstrosity. Others, in classic Kenyon College form, turned to poetry in order to confront troubling and contradictory aspects of archetypal stories:

BONE OF MY BONES by Che Pieper on Genesis 1-2

Sometimes now in our later years my husband

will talk about that time before time

which he knew well and speaks of fondly,

though much, I think, he forgets, and what little he knows seems to me made much more romantic.

I spent only moments there, when I was made of bone, but was not yet a women made of bone, and

when I was made of hard root,

but had not yet grown to be a tree.

It seemed to me a fine enough place, being polite,

but not for forever,

being polite.

I think to the future, as he makes his great statements about the immortal past.

He likes great statements, and names, and divisions. He is a product of his time, as am I.

I, who was voiceless in birth but not thoughtless and spent some time of my own in the immortal past (which seems, in reflection, not a place meant to last)

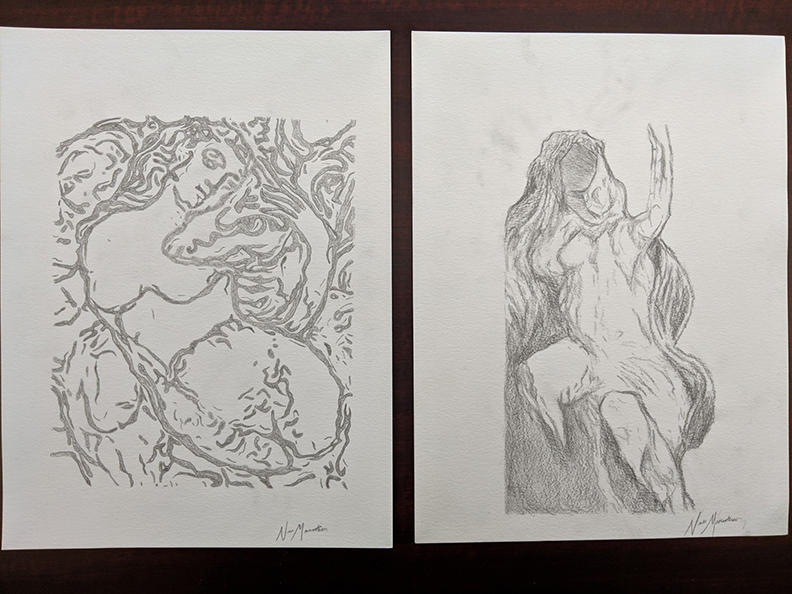

Artists examined socially-challenging texts with their own social commentary. One student explored the sexualized depictions of “whores” in prophetic and apocalyptic texts with her own representation of their internal experience (Nell Marootian, 2019):

Another wrote and performed a song inspired by Hosea 2 and the scholarship of Renita Weems and Rhiannon Graybill. She examined the trope of exploiting women’s bodies for divine narrative goals, writing,

“Said there’s adultery between my breasts

So you turned me into wilderness

They didn’t worship you properly

So you showed all of them, all my body”

In the end, the biblical text became an access point to a realm of student concerns that could be processed through biblical interpretation, just as countless interpreters before them used the biblical text to make meaning for their present circumstances.

The biblical studies classroom’s well-intentioned focus on biblical scholarship as the “proper” frame for interpretation can have the adverse effect of reifying the notion of an “original text” and “original meaning” ranked higher than its reception. In Nomadic Text: A Theory of Biblical Reception History, Brennan Breed writes about the limits of this framing, arguing instead that the biblical text is a “series of processes—text, reading, transmutations, and nonsemantic impact—whose nature it is to change over time” (205). If I were only to train my students to view the text as a static biblical context, I would distort the dynamic multiplicity of the text, whose meaning is never one determination of a text, but rather one of many potentials.

Students, like any reader, are participants in the actualization of meaning. By providing a chance for students to meditate on the Bible in a personal, intimate way, I could in a small way undo the teleology of my syllabus that might leave them with the impression that the original is the only, or the first, or the best meaning of a text. The truth is that the Bible has never remained in an original context but has always traveled from and to an array of contexts. Inviting my students into the processes of reading and interpreting Bible recognizes the potential of what the biblical text can do while also humanizing the classroom with their individual voices.

Krista N. Dalton is assistant professor of Religious Studies at Kenyon College.

All student work was shared with permission.