Above: Detail from Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.253. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

DANCE

Modern dance choreographer and soloist Daniel Nagrin (1917–2008), my former teacher and mentor, created a series of dramatic dance portraits that focused on ordinary characters from real life. Born and raised in New York City, the son of Jewish parents who fled the pogroms in Russia, his dances reflected a social consciousness and keen awareness of the world around him. His humanistic themes centered on conflicted, believable, and relatable characters in action. Below are photos of Nagrin in his Man of Action (1948), hailed by critics as a portrait of an urban executive’s stresses, strains, hurriedness, and frustrations of life.

Photo captions are mine. A special thank you to Lauren Robinson of the Museum of the City of New York and Libby Smigel of the Library of Congress.

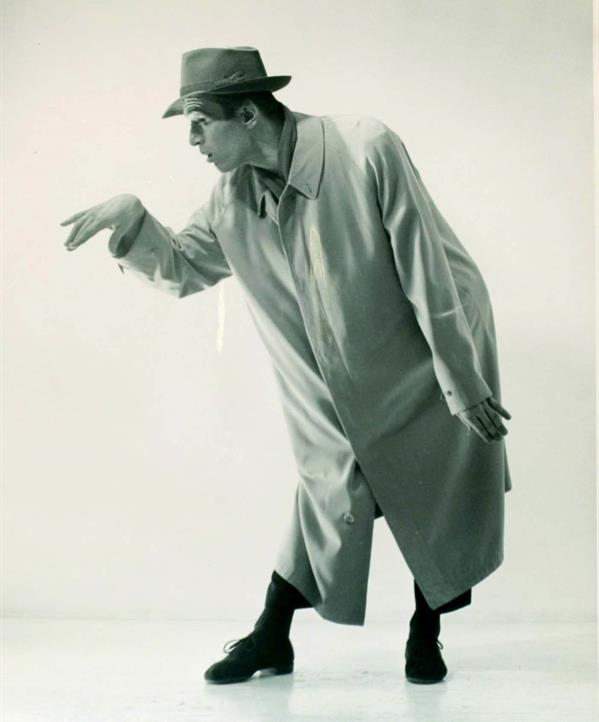

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.250. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

1. The busy businessman in a hurry, trench coat flailing as he furtively hails a taxi on a congested New York City street.

Nagrin’s portraits of everyday people in everyday activities became his hallmark. Always concerned about the Other and their plight, he focused on the messier, complicated web of human interactions and relevant issues from the world around him. Everything Nagrin produced through movement was the result of the character’s personality, found through improvisational exploration. Based in his X, which is the specific character, its core was found from doing specific tasks or functions such as Man of Action’s busy businessman who finally collapses from stress. To get into character while waiting in the wings to perform it, Nagrin fumbled with his coat buttons to conjure a frazzled, stressed-out demeanor.

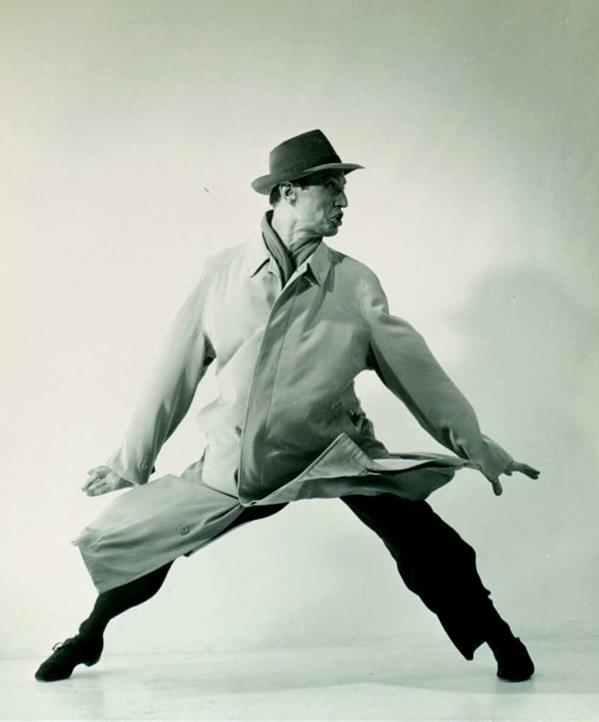

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.251. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

2. Forever rushing and impatiently waiting, the businessman checks his watch.

Nagrin’s characters always did something. The specific, deliberate actions, such as hailing a taxi or checking one’s watch, defined the character’s personality. These actions differed from pantomime and gesture, as they were based in an in-depth character analysis. In an informal telephone interview with Nagrin before his death, he stressed the “doing approach … based in acting techniques.” As an actor-cum-dancer, Nagrin appropriated and adapted into his dances the six-step acting theory of Moscow Art Theatre director Constantin Stanislavski. He choreographed in the way that was inherent and natural to both his professional aesthetic and his larger Jewish cultural ethos, grounded in thorough questioning. Nagrin’s six-step doing-acting questions are: who, is doing what, to whom, where and when, why, and what’s the obstacle or tension? I affectionately call it The Nagrin Method.

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.252. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

3. The man of action takes a dramatic, action-filled leap in a frantic scramble to catch a taxi.

Nagrin’s aerial acrobatics and outrageously daring leaps, one leg extended and the other folding under and kicking out, defied the limits and restraints of the human body. Nagrin was a master of noncodified, virtuosic, economically terse movement that came from an impulse for honesty and clarity. In 1954–55, he won the coveted Donaldson Award, today’s Tony, as Broadway’s best male dancer (Concert Program, July 31–August 5, 1956). A key feature of his work is stringing together a series of virtuosic actions that privileged content. His belief that content determined form is akin to modernist architect Louis Sullivan’s credo of “Form Follows Function.”

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.253. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

4. Desperately hailing another taxi, he pleads for it to stop.

Nagrin’s dances contain exaggerated gestures as movement metaphors or symbols mixed with satire and humor to reveal the character. Louis Arnaud Reid’s (1969) notion of metaphor as abstracted representations or essences that contain specific ideas and feelings about the character is applicable here. In this regard, it is possible to view Nagrin’s movements to define character as the essence or feeling projected through abstracted metaphors rather than simply literal gesturing. The result is a series of movement metaphors from which the form emerges and functions as a contextually relevant window to peer into the heart of his characters. Nagrin believed emotion and form (that is, the manipulation of steps, floor pattern, and space to create structure) were not primary but happen and follow because of the Stanislavskian focus on content through actions. It is content that provides meaningful reflection to the viewer.

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.254. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

5. Taking frantic, large steps forward, his body reverberates with the urgency of the moment.

Thematic inspiration for Nagrin’s dances came from his observations of and interaction with people in the immediacy of his time and place, that is, New York City and America in general. For instance, the idea for Man of Action came from watching a man in Grand Central Station during evening rush hour. Nagrin’s eye was caught by the frantic movement of a hurried, stressed-out executive who was moving faster than anyone else, who suddenly and abruptly changed directions, and then finally headed in another direction. By grappling with the human condition in ways that we all can relate to, Nagrin challenged audiences to think about their lives and values in order to bring about both reflexivity and constructive change in their thinking and personal lives. For example, in Man of Action, a hectic lifestyle is unproductive as it is stressful, disrupts clear thinking, and takes more time to complete tasks. His dances reflect his driving concern for the world around him that can be seen as a sort of social activism, which anthropologists call agency. The agentic actions of his characters metaphorically transform and remit powerful statements into aesthetic, meaningful social gestures. Akin to the Jewish value of tikkun ʿolam, or making the world a better place, it is my observation that the aim of Nagrin’s dances was to repair the world and make it better one person at a time through the agency of confrontation, questioning, and reflection. In addition, the notion of honoring ordinary, daily actions by transforming them into something holy is at the center of tikkun ʿolam.

Marcus Blechman / Museum of the City of New York. 76.20.255. Digital scan provided by the Library of Congress, Music Division, Box 16 folder 1, Daniel Nagrin Collection. “Man of Action”

6. Pulled in two directions, the conflicted businessman struggles with which way to go but gets nowhere.

A concert program note from March 2, 1958, indicates, “The Urban Man, in order to survive, must solve the problem of being in two or more places at the same time.” The wide, second-position lunges, frantic changing of focus, and frenetic awareness create a tension that literally and metaphorically attests to being pulled in two directions. Through Man of Action’s busy businessman, Nagrin exposes the futileness of a stressful lifestyle that still resonates in today’s fast-paced world. The hurried executive actually gets nowhere. His dance is an agentic, embodied expression of contemporary social and political actions that have the ability to move and motivate audiences. Thus, Man of Action is a collective portrait of us.

DIANE WAWREJKO is an adjunct dance and humanities faculty member at College of DuPage. Her research focuses on the agency and analysis of Daniel Nagrin’s choreography which is published in the Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement and Israel’s Dance Voices.