Above: Detail from merged photos—Left: Shluva (author’s grandmother’s grandmother), circa 1907. Right: Miriam, the author, circa 100 years later. Courtesy of the author.

DANCE

Growing up, a lingering tinge of shame cast a pall over my family’s household. I often felt I was carrying something not my own but that came from some part of me. Shame, that “painful feeling … of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging—something we’ve experienced, done, or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection.”i

My paternal grandmother spoke of her mother drinking vinegar to make her pink cheeks white in order to fit in. Along with other family lore that spun through my childhood years, I wondered if any of it were true or even possible. Father’s tales of having to sit in another section of the bus bewildered me. Grandmother’s description of her great-grandfather walking from Poland to England were spellbinding. Thus Meyer Fivel (I don’t even know how to spell it) became Maxwell Phillips (how I got my very Anglo surname juxtaposed with my very Hebraic first name). Then there were the crying episodes when she tried to tell us children about the Holocaust during our family lox-and-bagel brunches but claimed we did not have family members lost there. “But how could we not?” My adult voice echoed decades later. As a scholar I knew that it’s not always as important to know if a story is really true as much as it is to know the meaning the stories carry in a culture’s, family’s, or individual’s life. But questions nagged me.

Left: Shluva (author’s grandmother’s grandmother), circa 1907. Right: Miriam, the author, circa 100 years later. Courtesy of the author.

After a series of significant family loses in a short period of time, I began to wonder who my family really was. Where did I come from? Who were “my people”? I’ve spent so many years studying other artists’ lineages and their cultural histories through my work as a dance ethnologist (some that even could trace back nine generations), but I knew nothing of my own lineage or history. I’ve guided dance students to connect with their own heritage and transform that research into choreographic form, yet I had nothing of my own research-artistic creation to account for.

Spring 2018, while dredging through my late father’s art studio, I came across a box of elegantly framed monochrome photos I had seen in my grandmother’s home. Gazing over the faces and bodies of my lineage as I peeled the layers of stacked photos, I came across a photo I had never seen before. I was struck by her stark body stance, fearful look, and high-collared black dress. What was her story? Where did she come from? Why did I not hear stories of her? This was Shluva—my grandmother’s grandmother. She did not look a thing like me. “But somewhere,” I thought, “I have this woman’s DNA in me. I have her story embedded in my body architecture; her melancholy etched on my heart.” As reality collided with personal and artistic longing by mere happenstance, standing in my deceased father’s art studio garage, thus began a new work of research creation. This is the very short story of its bud becoming.

Rosie (author’s grandmother’s mother) betrothal photo, 1895. Courtesy of the author.

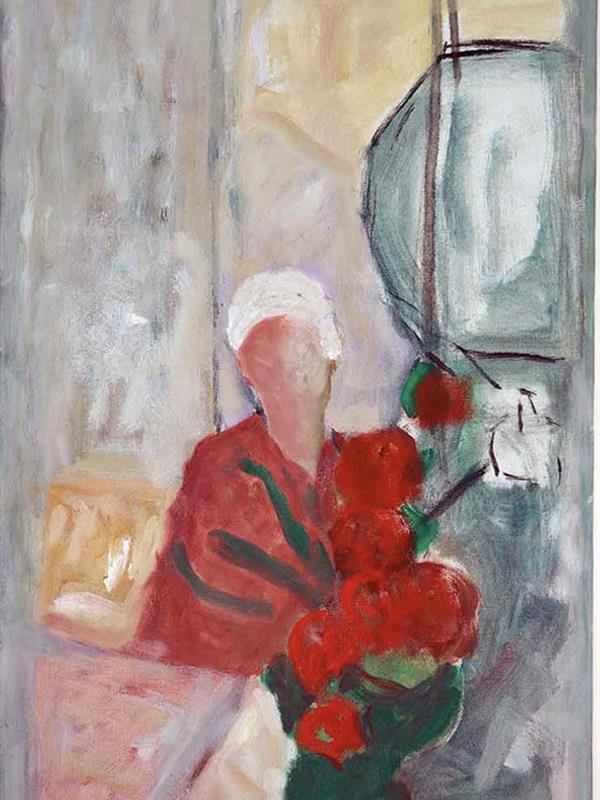

Pearl, (author’s grandmother) – painting by painter-poet Matt Phillips (author’s father), 1989. Courtesy of the author.

It is odd to be writing an article about a project in its nascent phase—one not yet researched, not yet performed. Yet I often guide my students to research and develop a written proposal for a future project. This represents one strand of that investigation.

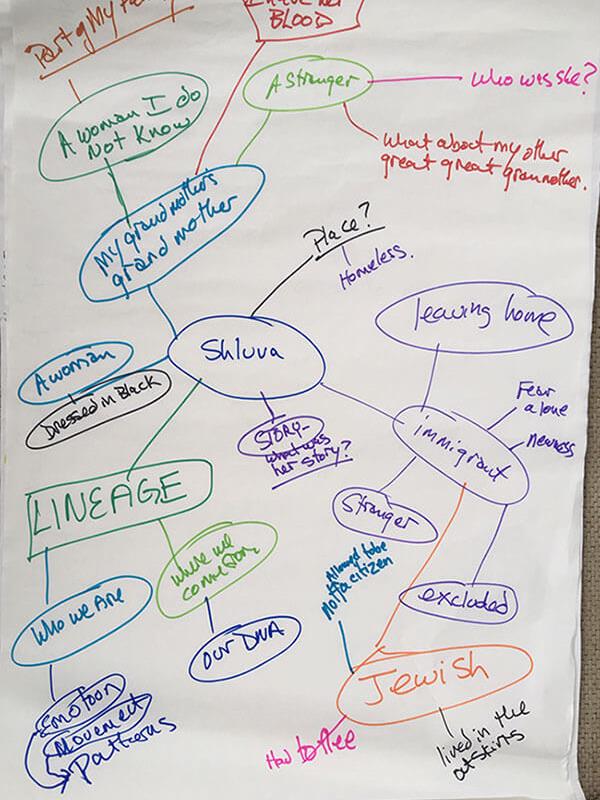

My Grandmother’s Grandmother (a.k.a. The Shluva Project), is a Practice as Research (PaR) PhD project that searches and researches my erased Jewish family lineage through the creation of a new choreographic work. The project explores themes of displaced and re-placed immigrants, excluded races, desires to be “other,” and family lore that perpetuates a sense of loss and lost identity through the generations. The background research interweaves ethnography, autoethnography, and narrative inquiry, along with ethnohistorical heritage and genealogical investigation. The artistic inquiry explores aspects of the qualitative research through dance improvisation, movement invention, dance-ethnography mapping of the choreographic event, poetic writing, drawing, and collaging. While there is a lot of fact-finding and genealogical charting in such an exploration that could lead me to fall down a rabbit hole, such as discerning birth names; plotting timelines of where and when my ancestors left or arrived in various locations; and interviewing distant family relatives for their stories and memories, I am more interested in what I will learn in traversing this process rather than in figuring out what is fact or fiction. (Although facts would be nice to discover.)

I appreciate the depth and interrogation that goes into scholarly research; at the same time, I value how creative process, with its techniques of abstraction, juxtaposing, metaphor-making, and intuition, can unearth meanings and discover connections between seemingly disparate elements. “Tangential thinking leads to new ideas.”ii Visual artist Kathleen Vaughan describes “art as a mode of knowing” and sees “the role of art as research and research as art less as creating new knowledge and more as calling forth, pulling together and arranging the multiplicities of knowledges embedded within.”iii I resonate with her statement, “embedded and embodied within a work of art, almost holographically, is a reservoir of knowledge and understanding, the ‘research’ of the work as conducted by the artist.”iv

It is through the research and art-making process that I hope to learn more about my family lineage, my own identity, and what life might have been like for my great-great-grandmother Shluva. How do I have some continuity of her within my personal makeup? I hope this project can shed light on how family histories and emotional palettes of our ancestors can be passed on and stored in the body. Then, how this embodied memory can be metamorphosed into kinetic choreographic form, thus leading to a renewed sense of identity and integration, if not healing genealogical pain.

Old cooking tools from author’s other grandmother that will be used in the performance; possibly to make potato latkes. Courtesy of the author.

Mind-map created as part of the creative process, April 2019. Courtesy of the author.

It is odd to be writing an article about a project in its nascent phase—one not yet researched, not yet performed. Yet I often guide my students to research and develop a written proposal for a future project. This represents one strand of that investigation.

My Grandmother’s Grandmother (a.k.a. The Shluva Project), is a Practice as Research (PaR) PhD project that searches and researches my erased Jewish family lineage through the creation of a new choreographic work. The project explores themes of displaced and re-placed immigrants, excluded races, desires to be “other,” and family lore that perpetuates a sense of loss and lost identity through the generations. The background research interweaves ethnography, autoethnography, and narrative inquiry, along with ethnohistorical heritage and genealogical investigation. The artistic inquiry explores aspects of the qualitative research through dance improvisation, movement invention, dance-ethnography mapping of the choreographic event, poetic writing, drawing, and collaging. While there is a lot of fact-finding and genealogical charting in such an exploration that could lead me to fall down a rabbit hole, such as discerning birth names; plotting timelines of where and when my ancestors left or arrived in various locations; and interviewing distant family relatives for their stories and memories, I am more interested in what I will learn in traversing this process rather than in figuring out what is fact or fiction. (Although facts would be nice to discover.)

Pearl (author’s grandmother) during lox & bagel brunch. Courtesy of the author.

White lace wrapped around your neck – I thought you

were afraid,

Gold chain dangling and draped – I got it wrong,

perhaps.

The more I gaze at you, now I see light,

Beaming from your eyes as if behind a shield of night.

Black ruffley pleated bodice – You seem stoic, strong,

Dark eyes, sleekly pulled back hair, big flat ears, long.

Round, you hold a half smile on your face, like some

secret you crave to share through your lace.

A torn and tattered photo. A name, a date, a city, in my

grandmother’s handwriting.

That is all I have of you.

You, who are a part of me.

What do I carry of you in what I do?

So many questions I have for you Shluva:

When did you leave?

When did you arrive?

How did it feel leaving and arriving?

What was your favorite recipe?

Did you husband treat you well?

Did you have a favorite color?

What was it like being a Jewish woman in unwanted places?

Did you have a special way to braid your challah?

How did you celebrate Shabbos?

What did you hope for your children?

What did you dream?

What did you desire?

How did you bake a cake?

What was your favorite song?

Did you know how to read?

To sing?

What brought you joy?

May I dance with you? May I dance for you?

May I dance into your past to know my present?

MIRIAM PHILLIPS is a U.S.-based dance arts practitioner, scholar, educator, and certified Laban/Bartenieff movement analyst. She specializes in Arts Practice, Dance Ethnology, Performance Autoethnography, and Flamenco. She is currently a PhD researcher and guest lecturer at the University of Limerick’s Irish World Academy of Music and Dance. Her chapter, "Hopeful Futures and Nostalgic Pasts: Explorations into Kathak and Flamenco Dance Collaborations" appeared in Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives, (McFarland Press, 2015). Her interdisciplinary choreographic work, Soleá de Edad, performed at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center in 2014, explored, through the flamenco idiom, how embodied memory reiterates and readapts through repetitive gestures, rhythms, and states of mind that weave through human life.

i Brené Brown, January 14, 2013.

ii Alys Longley, personal communication in Arts Practice workshop, University of Limerick, Ireland, April 15, 2019.

iii Kathleen Vaughan, “Mariposa: The Story of New Work of Research/Creation, Taking Shape, Taking Flight” in Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts (Edinburgh University Press, 2012), 171–170.

iv Ibid., 169.