Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

THE PROFESSION

I decided not to knock. This, after an hour on Moscow Bus 144 to Universitetskiy Prospekt; after slipping into Dmitiri Ulyanova 4/3 behind some resident with the key to the complex. Hundreds of Americans had been inside apartment 322. But that was back in the 1970s when Alexander Lerner—cyberneticist, Jewish emigration activist—had lived there. He had run weekly seminars in the living room for unemployed refusenik scientists, taking foreign guests to the park across the street to talk privately. But Lerner was long gone, in Israel since 1988, dead since 2004. What was the point of knocking? “Hello, zdravstvuyte, I didn’t use to live here, but I study people who visited someone who did? Can I look around?”

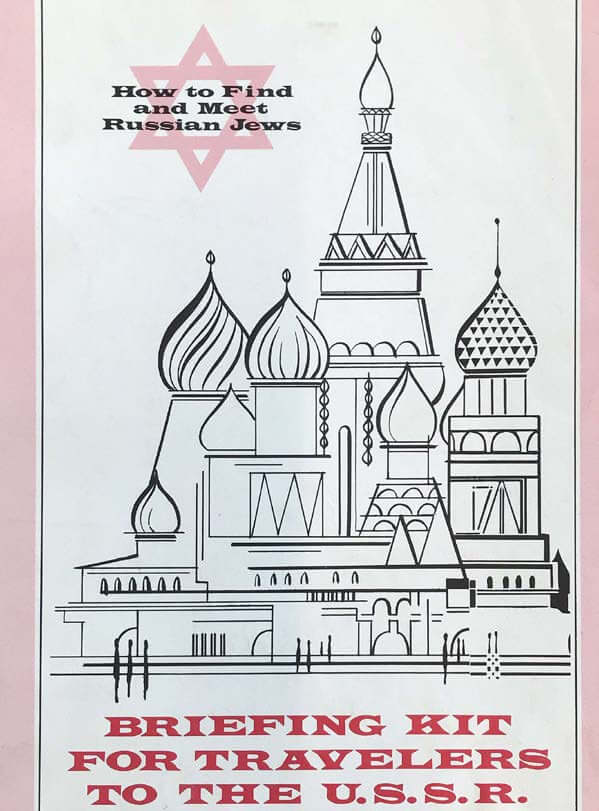

Reprinted from How to Find and Meet Russian Jews (American Jewish Congress, 1971). Courtesy of the publisher.

In my research on the campaign to free Soviet Jews, I’ve been examining Western tourists’ “aid visits” to refuseniks. How activists started the pipeline. How they briefed and debriefed. How travelers made sense of Soviet domestic and religious spaces. How they used spy novel genre conventions to retell their experiences. I’ve interviewed briefers and tourists. I built a database to get a statistical overview of the more than 2,000 travelogues at the American Jewish Historical Society—who, when, how long, where, arrests, expulsions. I’ve coded hundreds of travelogues for thematic analysis. Used the database sort feature to read every trip report from the 1970s in chronological order. I’ve even curated the photographs and hand-drawn maps for an artistic collaboration. The work has taken me to the Netherlands, Sweden, and France for conferences on Cold War tourism and on religion and travel writing.

But I had never traveled to Russia.

I landed at Domodedovo in December 2017. I’d have three days in Moscow, tacked on after the Swedish conference. I brought vintage Soviet Jewry movement address lists, copied from briefing kits and trip reports.

But I did end up learning things I had not known, or not known that I had known, or known in my head but not in my heart.

First stop, the Arkhipova Street synagogue. Directions came from the American Jewish Conference’s 1972 How to Find and Meet Russian Jews. (The title anticipated American clothing retailer Banana Republic’s June 1986 Soviet Safari catalog, the one that placed a story about visiting refuseniks next to ads for pith helmets.) “Walk alongside the facade of the GUM department store, which faces the Lenin Mausoleum. At the corner of Ulitsa Kuybysheva turn left.” It would have been easier had Moscow kept the Soviet-era street names.

The building was still functioning as a synagogue. No other addresses in the lists existed in that way. Apartments were no longer hives of activism where Jews from California and France met over vodka poured by Russian Jewish hosts. The refuseniks had moved out. The tourists had moved on. So what was I hoping to see? I am a sociologist of tourism. I know you can get crowds to stare at a rock if you slap a sign and a good story on it. Who was I kidding? I’d get to Lerner’s apartment and see a flat like any other. Any meaning I made of it would be in my head. And for that, I didn’t need to go. Or having gone, I didn’t need to enter to see how the tenth most recent occupant had renovated the kitchen.

What can students of historical travel learn by taking to the road? How can retracing routes in the present help us understand travel in the past? Which gaps in knowledge can travel help overcome? Which must remain as gaps? And how can we know the difference?

I told myself I was not going to see the places as much as “understand the geography.” Or “understand something of what it might have been like to try to navigate to the apartments.” Lots of hedging. But I did end up learning things I had not known, or not known that I had known, or known in my head but not in my heart.

This learning was not just intellectual, but emotional. I experienced it as respect.

Many trips started with a visit to Vladimir and Maria Slepak. I had known that their Gorky Street apartment functioned as the Soviet Jewry movement’s Grand Central Station Tourist Information Center. Walking there from the Hotel National taught me why. From Red Square to the Slepaks was a straight shot, fifteen minutes on the main boulevard. In New York terms, it’s like they lived on Broadway fifteen blocks north of Times Square. I understood then, viscerally, how lucky the movement was to have had such prime real estate. Of course, had the Slepaks not been so hospitable …

Schlepping farther out taught other lessons. Apartments were way off the beaten path, scattered all over town. Getting there took work. Thanks to the Soviet Jewry movement, I had a pocketful of help from 1979’s most famous émigré, Sergey Brin. Ironically, his tech surveilled me more than the KGB surveilled Soviet-era tourists. But having my GPS security blanket helped me realize how nerve-wracking it must have been for already jittery non-Russian-speakers to navigate multiple bus transfers in Moscow’s residential outer rings with no printed maps. This learning was not just intellectual, but emotional. I experienced it as respect.

That cell phone? A deliberate choice. Did I say I was “retracing the tourists’ steps”? Deep down, I longed to reenact. To experience what they experienced. I knew it was chimerical, but doesn’t tourism involve an element of play? I had the address, just off the Arbat, where I had once mailed letters to Leonid Barras, a refusenik boy who I symbolically shared my bar mitzvah with back in 1982. I could have headed over any time, yet I chose to wait until 1:00 a.m. to track down the apartment. Just like the Soviet Jewry movement tourists whose visits lasted into the wee hours. (By just like, I mean not at all.)

Against this temptation, Google Maps kept me honest. What self-respecting historical reenactor would ever use that? Would you believe me if I said I also stayed honest by ending my walk to the Slepaks’ by gift shopping at the Ekaterina Smolina boutique then occupying the ground floor of their former apartment complex? (Skirt and blouse for my daughter, turtleneck for my wife.) But there was the proof. Cell phone and shopping bags in hand, I could have no illusion that a trip from Trump’s America to Putin’s Russia would let me experience anything close to a Cold War crossing. I’ll finish the research still never having visited the Soviet Union.

Who said the past is a foreign country? I wish! I’d have booked a tour.

Shaul Kelner teaches the sociology of tourism as associate professor at Vanderbilt University. His longest work on Jewish travel is Tours That Bind: Diaspora, Pilgrimage, and Israeli Birthright Tourism (2010). His two most recent, are “Foreign Tourists, Domestic Encounters: Human Rights Travel to Soviet Jewish Homes,” in Tourism and Travel during the Cold War, edited by Bechmann-Pedersen and Noack (2020), and “À la rencontre des juifs de l’autre côté du rideau de fer: Récits de voyage de juifs américains et représentation du judaïsme en Union soviétique,” in Frontières et altérité religieuse, edited by Nijenhuis-Bescher, et al., (2019).