Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

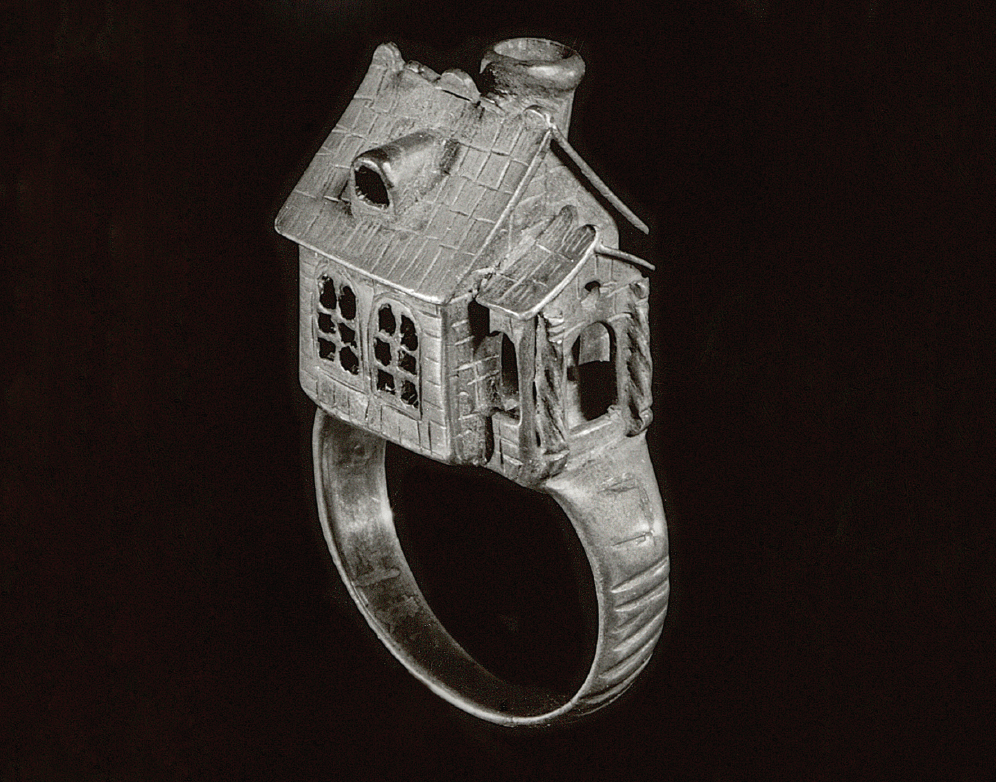

Wedding Ring in the Form of a Synagogue, ca. 1700. Silver. 1.75 x 1 x 0.56 in. Gift of Frederick Stafford, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, 59.54. Photo by Kevin Montague

For the past two centuries, Jews have played prominent roles as artists, art historians and art dealers, art critics and art collectors. The rich array of Jewish art, broadly defined, is prominently displayed in numerous Jewish museums. Yet American art museums, including those identifying as encyclopedic, have long had an uneasy relationship with Jewishness. Over the last quarter century, art museums have directly addressed one particular aspect of Jewish artistic experience—the Nazi-sponsored looting of Jewish art collections. But only three American art museums have established Judaica collections.i And curators often ignore the potential relevance of many artists’ Jewish identities and experiences in the interpretation of their work. For example, one reviewer noted that half of the American artists featured in the Whitney Museum’s recent exhibition Vida Americana: Mexican Artists Remake American Art, 1925–1945 were Jews (many of them Yiddish-speaking immigrants), yet their Jewish identities went “unexamined— and unrecognized—in both the exhibition and its catalogue.”ii This omission might have been less worrying had the catalogue not explicitly examined how American minority artists engaged with Mexican muralism. At a time when marginalized identities and perspectives are rightfully being integrated into the art historical narrative, what should we make of the fact that Jewish artistic experience remains largely “ghettoized” in Jewish museums?

As demonstrated two decades ago by Kalman Bland and Margaret Olin, the marginal place of Jewishness within the standard art historical narrative—and therefore the art museum—is a direct consequence of the discipline’s development in tandem with the emergence of nationalist ideologies and racial classifications in nineteenth-century Europe. An artistic canon dependent upon such categories simply could not accommodate the artistic expressions of a diasporic, religiocultural group.iii Moreover, these scholars’ strict literalist understanding of the second commandment— ignoring a wealth of rabbinic commentary—created a remarkably persistent myth that Judaism is antithetical to the visual arts.

In the twentieth century, as artists and critics grappled with antisemitism and assimilation, they hesitated to publicly embrace Jewish identities. In this context, the subtle references to the Holocaust in Mark Rothko’s otherwise “universal” abstractions were (and are) easily ignored, but critics reacted with consternation at overt visualizations of Jewishness. The Jewish art critic Hilton Kramer, writing in Commentary for a Jewish audience, famously compared Hyman Bloom’s 1940 painting Synagogue—expressionistically evoking an emotionally charged Kol Nidre service—to the “dismay one feels on finding gefilte fish at a fashionable cocktail party.”iv

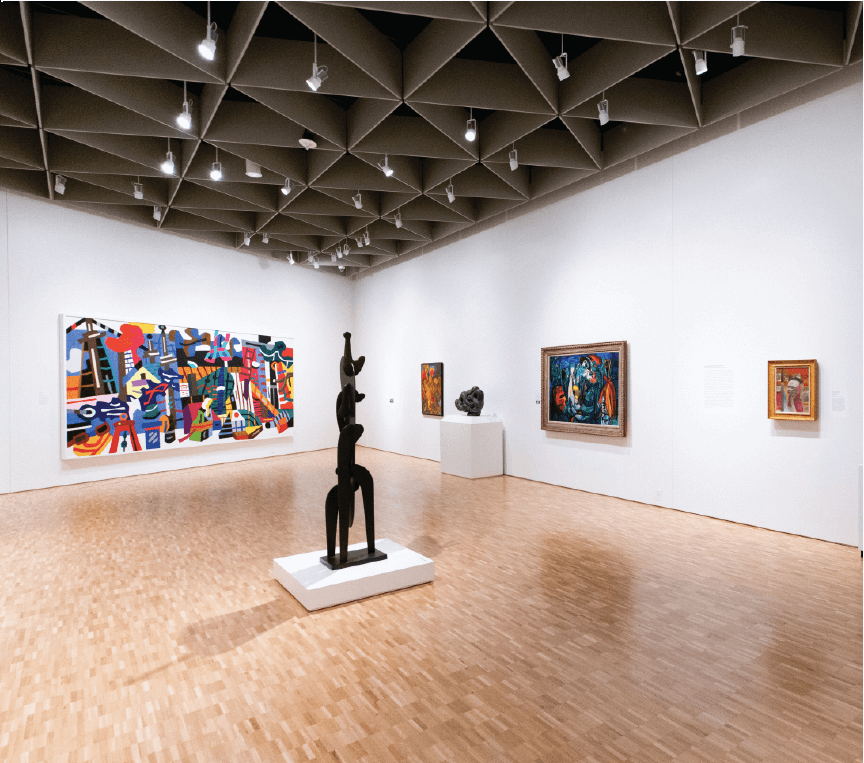

Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University. On the wall at right, works addressing by the Holocaust by Jewish American artists are incorporated into a display of midcentury American art. Two works by Japanese American artists referencing the war and Japanese internment are also on view. Photo by Shanti Knight

While Kramer’s comment reflects an ambivalence common among postwar American Jews, it points also to modern art’s uneasy relationship with “unmodern” religion. The fact that Jewishness is understood in the United States primarily as a religious identity—one, moreover, whose texts, rituals, and ideas are obscure to many—has not enhanced its visibility in the art museum. As I write, the University of Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery is exhibiting The 613 by Archie Rand,* a contemporary exploration of the mitzvot, or commandments, of Judaism. But such exhibitions remain comparatively rare. In fact, when I visited the MFA Boston in 2019 to study its Judaica collection, I found that the few works on view—ritual objects crafted at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Art School in the 1920s—were located outside of the main galleries, reinforcing their art historically marginal status.

The fastener at the bottom allows for a windmill or fan-form that opens to mimic the cyclical quality of the song’s violence.

Many American art museums are now engaged in the process of “decanonization,” critically reassessing the traditional art historical categories reflected in their collections. A panel on decanonization at the College Art Association’s 2021 conference examined how several university art museums are challenging narratives that perpetuate dynamics of power and privilege. Jews and Jewishness, however, are rarely considered within the context of decanonization, for Jews hold positions of power and privilege in the art world. But until the historical erasure of Jewish experience and perspectives from the canon is recognized, museums will continue to present distorted art historical narratives.

When I embarked on a major reinstallation of the European and American galleries at Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art (completed November 2019), I sought to complicate the canon through greater inclusion of women artists and artists of color, but also by integrating Jewish perspectives into the galleries where appropriate. Tellingly, the artworks key to my project had long been relegated to storage. In the medieval and Renaissance gallery, dominated (as such galleries usually are) by Christian liturgical arts, I installed the museum’s sole Jewish ritual object—a ceremonial wedding ring in the shape of a synagogue—contextualized with explanatory text and images. In this setting, the tiny object is a simultaneous testament to Europe’s pluralistic history and to the precarious status of its Others.

In our twentieth-century gallery, I emphasized international exchange, migration, diaspora—and yes, religious tradition—as drivers of modernist creativity. Here, I installed a small group of midcentury works by Jewish American artists Abraham Rattner, Jennings Tofel, and Jacques Lipchitz. Expressing their anguished reactions to the Holocaust by embedding references to Jewish ritual and mysticism in their compositions, their works subvert entrenched narratives that argue for the “universal” ethos of postwar American art.

Art historians once sought to construct a linear, hierarchical, and nationally homogenous artistic canon now acknowledged as exclusionary and misleading. Yet largely absent from decanonization strategies is a recognition that the exclusion of Jewishness—and the consequent delegitimization of Jewish artistic expression—has shaped the canon we seek to deconstruct. If art museums wish to present a full picture of human creativity, Jewish identity and experience— in all its diasporic heterogeneity—must be honestly and unapologetically visible.

JENNIFER MCCOMAS is curator of European and American Art at Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art, where she established the World War II-Era Provenance Research Project. She is also an adjunct faculty member in IU’s Borns Jewish Studies Program. For a forthcoming exhibition project, she is currently researching how American artists addressed the Holocaust between 1940 and 1970.

* See this issue's front cover image and article by Archie Rand for paintings from his series The 613.

iMuseum of Fine Arts, Boston: Minneapolis Institute of Art; North Carolina Museum of Art.

ii Jeffrey Shandler, “In a Whitney Museum Exhibition, Jewish Artists Go Unrecognized and Unexamined,” Hyperallergenic, January 6, 2021, https://hyperallergic.com/612895/in-a-whitney-museum-exhibitionjewish- artists-go-unrecognized-and-unexamined/.

iiiKalman P. Bland, The Artless Jew: Medieval and Modern Affirmations and Denials of the Visual (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); Margaret Olin, The Nation without Art: Examining Modern Discourses on Jewish Art (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

ivHilton Kramer, “Bloom & Levine: The Hazards of Modern Painting: Two Jewish Artists from Boston,” Commentary 20, January 1, 1955, 586.