Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

In 1869, the Jews of Sanaa warmly welcomed Joseph Halévy to Yemen, a man whom they believed to be Jerusalem’s latest emissary to their lands. Part preachers, part schnorrers, such envoys had become familiar visitors to Jewish lands in both the East and the West. Yet Halévy almost immediately began to raise eyebrows. Although none disputed his deep Jewish learning, his offers to pay for copies of pre-Islamic inscriptions made some suspect that the welfare of the Jerusalemite community was not his most fundamental concern. Ḥayim Ḥabshush, a Yemenite coppersmith, was intrigued. He was already a collector of ancient inscriptions, which he used to make magical amulets. He was also interested in tracking down the ten lost tribes, who were rumored to be living hidden away in the Arabian deserts. Realizing that this rabbi was not who he seemed, and thinking him to be a mystic and magician, he hoped to become his disciple and gain knowledge of occult secrets. Ḥabshush was quickly hired by the mysterious rabbi, but, once in his service, he discovered that the rabbi possessed an entirely different kind of knowledge.

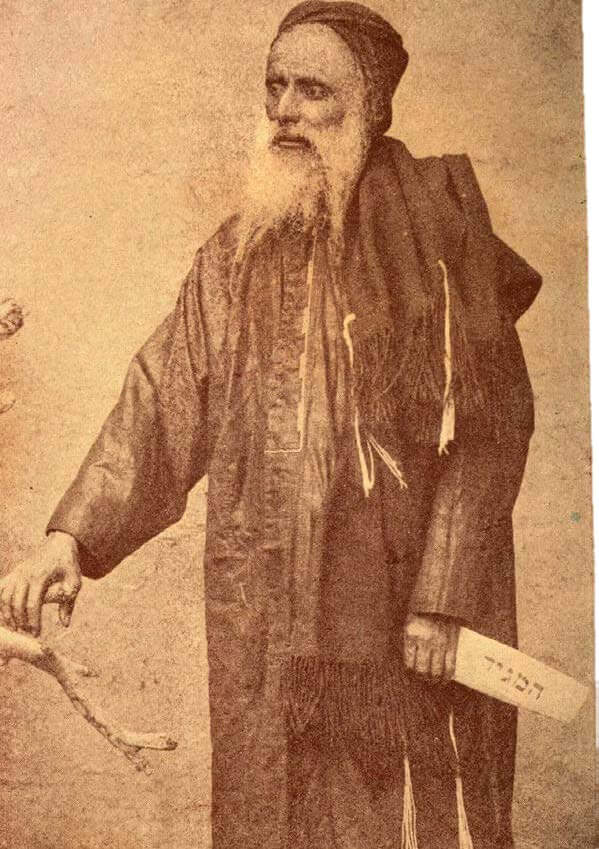

Portrait of Hayyim Habshush with a European Hebrew-language newspaper.. Courtesy of the author

Joseph Halévy was not from Jerusalem, but he was indeed a learned rabbi who, aided by a photographic memory, had mastered Talmudic literature and was able to hold his own in traditional Jewish society. Ḥabshush, however, discovered that he had been wrong to see Halévy as a magician. On the contrary, Halévy prized rationalism and rejected Judaism’s traditions of mysticism and magic. He had been previously employed by a Jewish organization, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, that sought to better the condition of oppressed and impoverished Jews by uniting them in a shared commitment to modernity. To this end, he had served as a teacher and administrator in schools in the Ottoman Empire and Europe and had also undertaken a mission to Abyssinia to save its Jews from both poverty and conversion to Christianity. But Halévy had come to Yemen with a different agenda. He had been sent there by the French academy to locate and transcribe pre-Islamic inscriptions, not to save its Jews. Despite the secular nature of his mission, Halévy had been chosen by the French thanks in part to his rabbinic training. Yemeni historians frequently refer to the nineteenth century as “a time of corruption.” Famine and disease decimated a population already wracked by continual conflicts between warring tribes. A foreigner’s only hope of avoiding such violence was to attach himself to Yemenis who played no part in intertribal struggles. As clients of Yemeni tribes, Jews were not directly involved in such conflicts and their geographic dispersion across Yemen made them well-placed hosts for a foreign would-be explorer. Indeed, over the centuries, several Jerusalemite rabbis had taken advantage of precisely this system to facilitate their travel in Yemen. A Jerusalemite rabbi, the French academy reasoned, had the best chance of safe travels in Yemen, and Halévy, who enjoyed a reputation as an Ottoman Jewish sage, was judged to be an ideal candidate to assume that guise.

As lone travelers surrounded by weapon-carrying Jews with very different mores from their own, they are at a loss as to if and how they should intervene.

Ḥabshush soon overcame his disappointment that Halévy was not a magician and became enthusiastic about the academic world Halévy embodied. Nonetheless, he did not view Halévy uncritically. Impressed as he was with Halévy’s secular wisdom, he also thought that Halévy’s obsession with ancient artifacts had blinded him to the needs of contemporary Yemeni people and to the beauty of Yemeni Jewish culture. Ḥabshush fretted that Halévy’s scholarly reports would not capture the land and people to which he was so deeply attached. He praised Halévy as the source of his enlightenment but made no secret of his distaste for Halévy’s aloofness, even publishing an open letter in Eliezer Ben Yehuda’s newspaper Ha-ʾor, in which he publicly criticized him. Receiving no response from Halévy, he decided to write a rival account of their journey. It was designed to serve as a guide for Ashkenazim to Yemen’s diverse Jewish communities and as an invitation for them to engage with their “Eastern” brethren. He called his book A Vision of Yemen.

Throughout his work, Ḥabshush dwells on the moral duties of travelers. He is profoundly sensitive to the fact that the mere presence of a traveler in a land seldom visited by foreigners can change it forever. It was because Halévy shared his poor opinion of the Zohar with locals, Ḥabshush claims, that a vituperative conflict over the status of the Kabbalah erupted among Yemeni Jews and permanently divided their community. Ḥabshush’s searches for inscriptions led some to believe that he was a malicious magician or a treasure hunter, bringing suspicion on his unsuspecting Jewish hosts and disrupting relations between Jewish communities and their Muslim neighbors. He also talks about his impact

on individuals. For example, he reproaches himself for inadvertently bankrupting one of his hosts, who parted with all he had to accommodate his guests, so highly did he prize the virtue of hospitality. Ḥabshush was a humanist who believed in the potential for travel to unite people and promote understanding, yet, perhaps more than most travelers of this period, he was aware of the risk of negatively affecting the people he encountered.

Ḥabshush is particularly sensitive to the question: Ought travelers intervene to correct the injustices that they see or are they instead bound to avoid imperialistically imposing their values on others? Ḥabshush does not limit these discussions to non-Yemenites. In rural regions remote from his hometown of Sanaa, he too feels himself to be a foreigner, grappling with values and customs very different from his own. The questions surface time and again, and most tragically when he and Halévy stumble upon a Bedouin Jewish family, bound by codes of tribal honor, who are about to kill their daughter for becoming pregnant before marriage. As lone travelers surrounded by weapon-carrying Jews with very different mores from their own, they are at a loss as to whether and how they should intervene. Ḥabshush considers offering to perform an abortion to save the woman. Then he considers how he might save her by marrying her and taking her away from the only family and community that she has known. And could it be, Ḥabshush wonders, that his deep attraction to this beautiful woman is skewing his judgment? Does it matter that the “help” he has to offer is also self-serving?

Ḥabshush’s travelogue was written at a moment when travel had become faster, aided in part by the rise of European and Ottoman imperialism, and Jews were becoming aware of the diverse practices of world Jewry. Ḥabshush’s position as a “native guide” to a European traveler, and as a traveler himself to unfamiliar parts of his own land, placed him in a unique position to reflect on the ramifications of this exciting and fraught new era. His reflections serve as a remarkably prescient, nuanced, and deeply humane attempt to critique and celebrate the opportunities of discovery and self-discovery offered by such explorations.

Alan Verskin is associate professor of Jewish and Islamic History at the University of Rhode Island. His most recent book is A Vision of Yemen: The Travels of a European Orientalist and His Native Guide (Stanford University Press, 2019). His forthcoming book is Diary of a Black Jewish Messiah: The Sixteenth-Century Journey of David Reubeni through the Middle East, Africa, and Europe (Stanford University Press, 2023).