Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

Douglas Rosenberg

The Performance of Travel (The Performance of Mobility)

Walking shares with making and working that crucial element of engagement of the body and the mind with the world, of knowing the world through the body and the body through the world. … Our very sense of self-worth seems predicated more and more

on our suffering through the inconveniences and psychic destabilizations of ungrounded transience, of not being at home (or not having a home), of always traveling through elsewhere.

― Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

This is the Travel Issue. For artists working in the postmodern era, mobility and nomadism are a particular kind of currency. To be nomadic (by choice), to have the privilege and possibility of travel, both enables an artist to become a part of the global art world and accords the citizenship that goes along with it, and a well-stamped passport is less a symbol of a bourgeois lifestyle than a notational mark of the contemporary, socially engaged artist. As we know, Jews have been, at various times in history, people of the Diaspora, “traveled” against their will, or been peripatetic as a consequence of their will; they have been forced to cover ground to destinations not of their choosing and have deliberately traversed great distances to arrive at new lands. We can think about travel, particularly in relation to Jewishness, in many ways. This collection of artwork in the Travel Issue revolves around the way that artists think about the question of travel and perhaps more broadly about mobility itself in the twenty-first century. The artwork included here is not about travel as a metaphor, but rather travel as a performance of mobility, the actual movement across space and time. It is perhaps, a bit at odds with the “idea” of travel in the era of Zoom and VR, but bodies in space do things that virtual bodies cannot. Footprints on the moon or footprints created in the sand of a vast desert over forty years of wandering are impressions of human interaction, however ephemeral. For Jewish artists historically, I would suggest, travel, walking, witnessing, being in public, making artwork that is, in fact, both Jewish and public, is a hedge against erasure. Travel tourism or travel by train to a destination not of one’s own choosing is still travel, however, the significance of each is consequential when thinking about how embodied histories contribute to artistic and creative expression.

How to make art about the emotional resonance of Jewish identity while employing contemporary tools with a nuanced eye toward Jewish-ness? A project of mid-century postwar Jewish artists was to make art that did not look Jewish in the way that art of the same period did not look Christian, or perhaps more specifically ethnic in the way that Old World Jewishness portrayed itself. To be modern after the war was to transcend such visually referential tropes. Postwar abstraction is about nothing as much as transcendence through ritual, through the negation of the figure, and through the conscious essentializing of art generally. For many artists of that era (many who were Jews), the creation of objects, images, gestures, and spaces of contemplation were often mined from the generational trauma of the twentieth century itself.

Douglas Rosenberg. Untitled Performance (Home), Krefeld, Germany, 1982.

This territory is something I have explored in my own artwork as far back as the 1980s when I found myself drawn to the creative energy of Berlin’s art scene. Prior to traveling to Germany, I had no expectations about the emotional weight of that trip (this was also well before the wall came down). Upon spending time in Berlin and surrounding cities, I found myself both emotional and even angry in ways that I did not expect or understand. While I did not travel to Germany to visit Holocaust sites (I went instead to show my own artwork in various art spaces), my impulse to mark that space with my own outrage resulted in several guerrilla- style installations and performances on the streets of Krefeld and elsewhere. My own embodied experience of Jewishness has indeed marked the way I have made artwork subsequently and the way I think and write about the work of artists grappling with similar embodied experience.

There are familiar tropes of wandering throughout the literature of Jewish life, most of which are quite familiar. There are also numerous literary tropes of the flaneur, of peripatetic scholars and thinkers, and of travel as a kind of romantic aspiration. Writers such as Walter Benjamin and the aforementioned Rebecca Solnit have presented us with much to flesh out our ideas about travel in the context of aesthetic fulfillment. For the artists in this curation, travel is inseparable from the creation of their artwork itself. It locates both the artist and the subject of the work in the place it needs to be. It does so in order to fully function as a gesture of social consciousness or religious questioning, or tikkun ‘olam. For some, “travel” is part of a more personal or spiritual questioning, but all of this work is arguably set within the context of the global village we have come to live in. Travel is often a part of the broader project of mapping and/or cartography, which produces documents that ostensibly locate us in the world. However, documents such as maps are temporary and contingent on the moment that they are introduced; beyond that moment they tend quite quickly to become irrelevant, an archive of a landscape that has since been reconfigured by one means or another. For artists, mapping often takes the form of tracking experience, the personal performance of visibility, or a kind of interpretive objectified manifesto made solid and permanent. The work in this context is situational, it is about the space it inhabits, though in some cases, that may be an imaginary or aspirational space. In her book, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, the author Miwon Kwon notes, “While site-specific art once defied commodification by insisting on immobility, it now seems to espouse fluid mobility and nomadism for the same purpose.” Such is the landscape of postmodernism generally: fluid, often highly intentional and subject to slippages and the quickly changing politics of representation. In writing about the artists of the Spertus Museum exhibition The New Authentics: Artists of the Post-Jewish Generation in 2007, curator Staci Boris deploys such terms as, “instability,” “multiplicity,” “openness,” and “fluidity” to explain the conditions of artwork that addresses Jewish identity in the twenty-first century. The work featured in the Travel Issue navigates all of the above, doing so within a fluid understanding of both Jewish identity and of art practice. Interdisciplinarity, diversity, and intersectionality are all topics of the cultural moment and also part of the dialogue taking place within the generational shift among Jewish-identifying artists to a more inclusive and polyvocal vision that at times may seem unfamiliar. In the contemporary Jewish experience, within the arts writ large, we see both a search for new narratives and a return to ritual often within the same works of art.

.jpg?sfvrsn=9745266c_0)

Karey Kessler. A Portable Homeland, 2018. Watercolor on paper. 120 in. by 36 in. Photo by Art & Soul Photo, Seattle

In her project, A Portable Homeland, the artist Karey Kessler “ plays on the idea of the Torah as a portable homeland,” albeit one that she can physically carry with her. Perhaps echoing the observations of German poet Heinrich Heine, the paintings read like maps, as the artist explains, to “explore what it means to be connected to a specific place—the geology of the land, the water, the buildings; yet, at the same time connected to a spiritual realm that is beyond the boundaries of physical space and time.” The project challenges the more traditional notion of homeland as a particular place and instead depicts it as a boundaryless place of space and time.

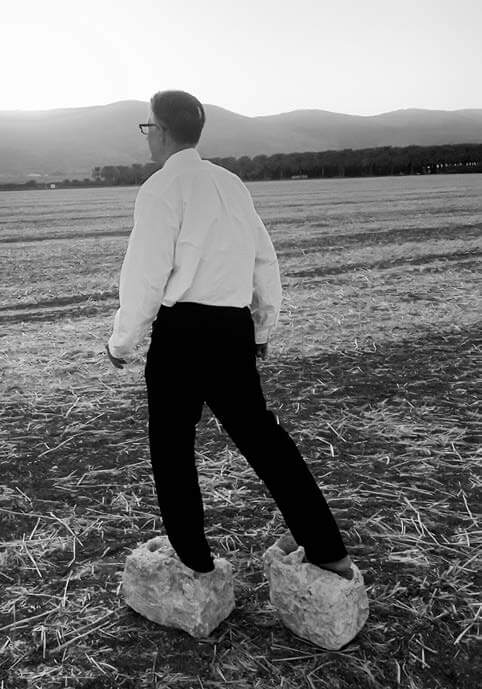

Ken Goldman. L’lo Reshut - Eruv Walk, 2015. Digital archival print, performance record. Photo by Gideon Cohen

Ken Goldman’s work deeply engages primary religious sources that merge with his concern for issues of faith, gender, community, otherness, and mortality. Working from Kibbutz Shluḥot in Israel, Goldman’s work is clearly framed by both the landscape and materiality that surrounds his home. His choice of material seems often based on the nature of the story he is telling, and he freely roams through both style and application, at times using the stone that is indigenous to Israel, his own body, performance, and an index of both two- and three-dimensional techniques. In the performance piece Lelo Reshut—Without Domain, Goldman “explores and reacts to the drastic changes in ideology and lifestyle rocking the foundations of his kibbutz home.” Goldman’s project here alludes to the work of feminist artist Janine Antoni’s piece Touch (2002) and thus aligns him within a history of the feminist exhortation to make the personal political.

Ken Goldman. All Who Walk, 2021. Carved Local Stone. 11.8 in. by 11.8 in. by 7.9 in. (each piece). Photo by Gideon Cohen

In the single photograph, we see Goldman in the process of navigating a slackline or tightrope, which he describes as an eruv ( a symbolic rabbinic device used to unite individual domains into one shared domain). Goldman describes the piece as “a symbolic attempt at the reunification of his community and its members after they voted to no longer preserve the classic collective kibbutz lifestyle it had maintained for nearly 70 years.” For this performance piece and subsequent photo, the artist attached a red line three meters above ground at the height of the existing eruv and walked a section of the eruv opposite his home. The photo, while certainly a documentation of a work addressing a very local community, traverses the world as a symbol of resistance. Such is the peripatetic nature of images in the digital realm; as the artist travels the length of the rope/eruv, its documentation travels, as well, across and throughout the global village. His project, Four Cubits (Four Amot Walk), refers, in Jewish tradition, to a person’s private space—a concept that resonates with contemporary meaning in the moment of a global pandemic. Goldman hand-carved the stone footwear, deliberately creating an impediment to his ability to travel freely, thus amplifying the burden of others for whom travel is not possible or presents extreme distress. Here, traveling the distance of four cubits becomes a monumental task.

Alona Bach. A digitale rayze / A Digital Journey (Shidlovtse Yizker-bukh), 2021. Digital.

Alona Bach and Ben Schachter both address mapping. While Bach’s A digitale rayze / A Digital Journey (Shidlovtse Yizker-bukh) reads more like a graphic novel or an illustration one might find in a children’s book, Schachter’s images of eruvim read as branded outlines of familiar states such as Wisconsin, California, or Texas. However, eruvim are local, and upscaling the shape and footprint of this sort of mapping confounds contemporary ideas about territory and statehood, or even nationalism. Bach’s map contains references and visual cues to its digital origins; it is the product of an Internet search, perhaps, or a virtual signifier of the possibilities (or lack thereof), of travel for those citizens who are observant or speak and or read Yiddish. Either way, A digitale rayze / A Digital Journey (Shidlovtse Yizker-bukh), visualizes and imagines a closed system, even as the Internet makes it globally accessible.

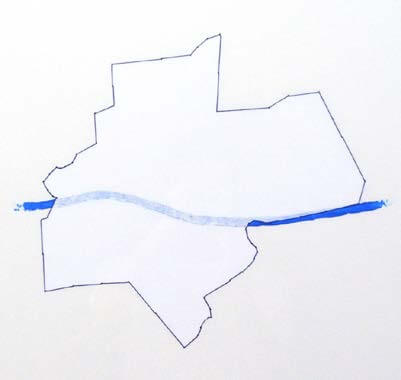

Ben Schachter. Squirrel Hill Eruv, 2007. Acrylic and thread on paper. 22 in. by 30 in. Photo by the artist. Collection of the artist.

Schachter’s drawings suggest the boundaries of eruvim, though are rendered in the way that we are used to seeing drawings generally, with titles, dates, and signatures at the bottom. They seem like conceptual renderings of random spaces, yet the titles (Squirrel Hill, Venice) convey that they are indeed controlled religious spaces. The visual culture of the two representations of mapping (Bach’s and Schachter’s) land differently for the viewer, each denoting a similar experience of travel, yet in ways that steer us, the viewers, in quite different directions.

Hannah Schwadron (Choreography), Malia Bruker (Cinematography) with dancers Amanda Waal, Luka Kiwus, Susanne Nazarigovar, Selin Yasar, Samuel Aldenhoff, Athena Fahimi Vahid. Klasse, 2015. Film still.

Hannah Schwadron is a choreographer and filmmaker. For Schwadron, embodiment is at the core of representation. Klasse is a dance film shot in a historical classroom at the Israelitische Tochterschule with students from the Ida Ehre Schule in Hamburg, Germany, in May 2015. Israelitische Tochterschule existed from 1884 to 1942 and after the creation of the Nuremberg Laws, the school accepted students who were expelled from other schools because of their Jewish beliefs. Schwadron worked closely with a mixed cast of German middle-school students and professional dancers to “bring to life” shards of letters written between young classmates as they left Germany on the Kindertransport. This is not a documentary but a work made for the camera, meant to convey the emotional resonance of such an experience. What we see here are stills from the film, tightly framed compositions that could be, by themselves, photographs set within an old school classroom kept just as it was during the war. Schwadron notes that, in fact, “the chairs, the desks, the chalkboards and the solid walls [left as they were] are reminders of the haunting fixity of place against the visceral trace of memories left as records of a tortuous time.” By performing this project in real time and space, Schwadron releases its energy into a socially conscious work of art that is both illuminating and illuminated via the film itself.

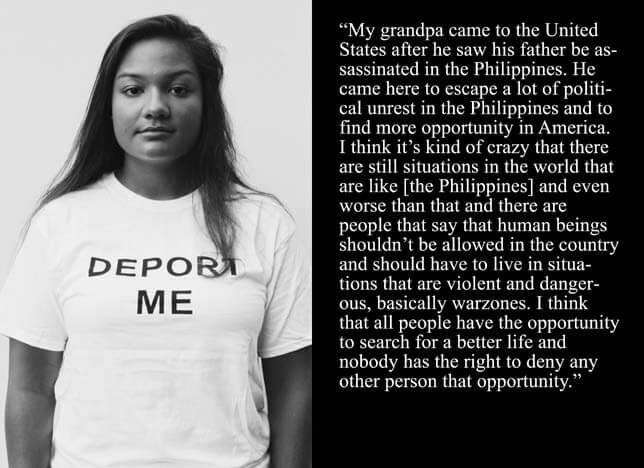

Jacob Li Rosenberg. Deport Me (Delaney), 2018. Dimensions variable.

Jacob Li Rosenberg makes artwork that is overtly concerned with issues of social justice. He is a Chinese American Jewish artist whose family tree includes Jewish immigrants from Russia and Poland and Chinese immigrants from the village of Taishan, both of whom were driven from their respective countries under similar yet particular circumstances. In speaking about his Deport Me Project, he recalls the following by Martin Niemöller:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Socialist. Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Rosenberg asks participants to be photographed wearing a T-shirt printed with the words “DEPORT ME” in order to echo the gesture that free people have often enacted when the rights of others are in jeopardy, a gesture of solidarity that confuses those that would prey on the undocumented, the “outsiders” and the “others.” Not dissimilar from the gesture made by non-Jews of placing a menorah in the window as an act of solidarity, The Deport Me Project asks viewers to consider, in the anti- immigration frenzy, how we know who among us is a citizen, who has the right to be among us, and who decides? It is an activist art project that is intended to raise awareness of the unjust and inhumane practice of family separation, mass deportation, and denial of due process to asylum seekers. Deportation often reverses the long and arduous travel that has brought individuals to this country; it effectively returns them to the cycle of endless diaspora that dehumanizes and exhausts both people and institutions that would try to unravel such practices. The first trio of images is seen alongside text panels capturing the individual’s family history of travel and displacement. The second group of photos are individual portraits of New Yorkers, most of whom have traveled to the city by choice. They stand on lower Second Ave. with the background of midtown and the Upper West Side in the distance, attainable but seemingly quite a journey away. Rosenberg, whose own ability to travel freely is unimpaired, despite his familial immigrant origins, gathers groups of people in cities across the country, asking them to stand in solidarity with their community members by posing with the emphatic prompt across their chests. Why not Deport ME? Take me instead.

Laurie Beth Clark. Versteckte Kinder, 2002, 2012, ongoing. Installation. Photo by Michael Peterson

The artist Laurie Beth Clark attended yeshiva before studying art in college. An inveterate traveler, she makes artwork that is deeply rooted in community, social justice, and often in ritual in cities around the world. Clark is represented here by two projects. The first, Versteckte Kinder, is a series of one hundred “dollhouses,” each one marked by a mezuzah (the ritual indicator of a Jewish home), a tiny book, and a small loaf of bread. The houses are hidden along the path of a forest in Darmstadt, Germany, and on the adjoining trails. Clark traveled to Germany to participate in a show curated by Ute Rischel in 2012 and was moved to honor a relative who was one of the children hiding in the woods in Poland during the war. Clark’s gesture toward healing is left in the forest to be found by walkers and travelers for whom the small houses will be a surprise. Clark notes that she “does not expect that spectators find all of the houses. Rather, it is my hope that each person glimpse one or two of the houses in the course of walking the trail or during other routine uses of the forest and be reminded of other ways the forest has been used in recent German history.”

In 2008, Clark undertook a series of performative actions called Masked Walks, years before the current pandemic of COVID-19. In speaking with Clark, she noted that she “began working with the fabric face masks after a trip to Vietnam, where the masks are widely worn to protect cycle motorists and pedestrians against environmental contaminants (fumes and dust) in urban spaces.” She stated, “I was initially struck by both their creativity (the masks are made from a wide range of fabrics) and their futility (as fabric masks may provide comfort but do not filter out the worst respiratory threats).” The walking project was devised in a period when Clark began to travel extensively in Africa, Asia, and South America. She chose to have a set of masks made from camouflage fabric as a way to contemplate her own increasingly conspicuous outsider status.

Laurie Beth Clark. अंग्रेज़ी (India), 2008. Performance. Photo by Michael Peterson

The performances went on unannounced, with no communication about them in parts of the world where Clark’s racial difference from dominant populations was blatant. Clark generally performed a single walk per country visited, and performed a second if she visited a region where there was or had recently been an “identity-based” independence movement—from Quebec to Rapa Nui—or where there was ongoing “apartheid.” In South Africa, for example, walks were done in both townships and gated white enclaves. However, when she continued the work in Europe (especially in Austria, Poland, and Germany, where her research took her to concentration camps, Jewish history museums, and other Holocaust commemorative sites), she notes that her sense of her own ethnic identity was elevated. She states that her “marginal status as a Jew is not ‘marked’ or visible in the same way as [her] whiteness is in Asia or Africa.”

I have spoken with Clark at length about the question of how and in what context Jews are perceived as white and the extent to which white privilege has dominated discourse surrounding Jewishness in recent times. Both of us were brought up in the 1950s and 1960s with an explicit understanding about how one could pass for white (with nose jobs and name changes being common), especially in the Jewish coming-to-America tropes played out in Hollywood films. While Clark’s work does not “look Jewish” (and I say that with some irony intended), like all of the work included in this curation, it performs a version of Jewish empathy and mitzvot. It is social practice and or social justice embodied within a visual culture of contemporary art.

Ultimately, one photograph from each of Clark’s walks is printed “life size,” meaning that the size of her own body in the print duplicates her own body measurements. The prints are then installed in the gallery to match the eye level of the viewer. Thus each gazes at the other, perhaps metaphorically wondering whose gaze is “on trial,” whose gaze is suspect, and whose gaze is the gaze of a free person in the world: who gets to look, and who gets to be looked at?

Douglas Rosenberg

University of Wisconsin—Madison

N.B. As this is my first project as art editor for AJS Perspectives, I want to express my admiration and gratitude to Samantha Baskind who preceded me in this position. Professor Baskind’s writing has elevated the discussion of Jewishness in art to a space of equity in contemporary art history. I am grateful to have encountered her work at a time when I was wrestling with my own ideas about how Jewishness fit into the larger discourses of art writ large. Her work with AJS Perspectives has set a high bar for us all.