Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

The eastern border of the European Union runs through land that for over four hundred years, from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, was the most important center of Jewish culture in the world. The blooming of this culture began when the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania created a dual state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, from which contemporary Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine came into existence. The events of World War II and the Holocaust destroyed this world, yet Jewish cultural heritage has been permanently imprinted upon the cultural landscape of this part of Europe. Jewish heritage travel here is inherently ambivalent. While survivors often notice what is missing from their childhood landscapes—the absence, subsequent generations sometimes focus on what does remain. At the same time, for local communities, traces of Jewish history can be an important element of their own identity.

Tourists in the Łańcut synagogue (Poland), 2015. Photo by Monika Tarajko. Courtesy of the Shtetl Routes, www.shtetlroutes.eu

Shtetl Routes is a heritage interpretation platform and a cultural tourism trail in the footsteps of Jewish cultural heritage in smaller towns in central and eastern Europe. The idea arose from the documentary, artistic, and educational work connected to the Jewish heritage of Lublin as part of the work of the Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre Centre, a Lublin-based municipal cultural institution created in the early 1990s. The Shtetl Routes project began to operate in 2013 in the framework of the Cross-Border Cooperation Programme Poland – Belarus – Ukraine funded by the European Union.

While organizing the project, we considered the following questions: How should the multicultural heritage of a borderland area be discussed? Can the current residents, mostly non-Jewish, relate to local Jewish history as their common heritage? How should Jewish heritage be presented as part of cultural tourism?

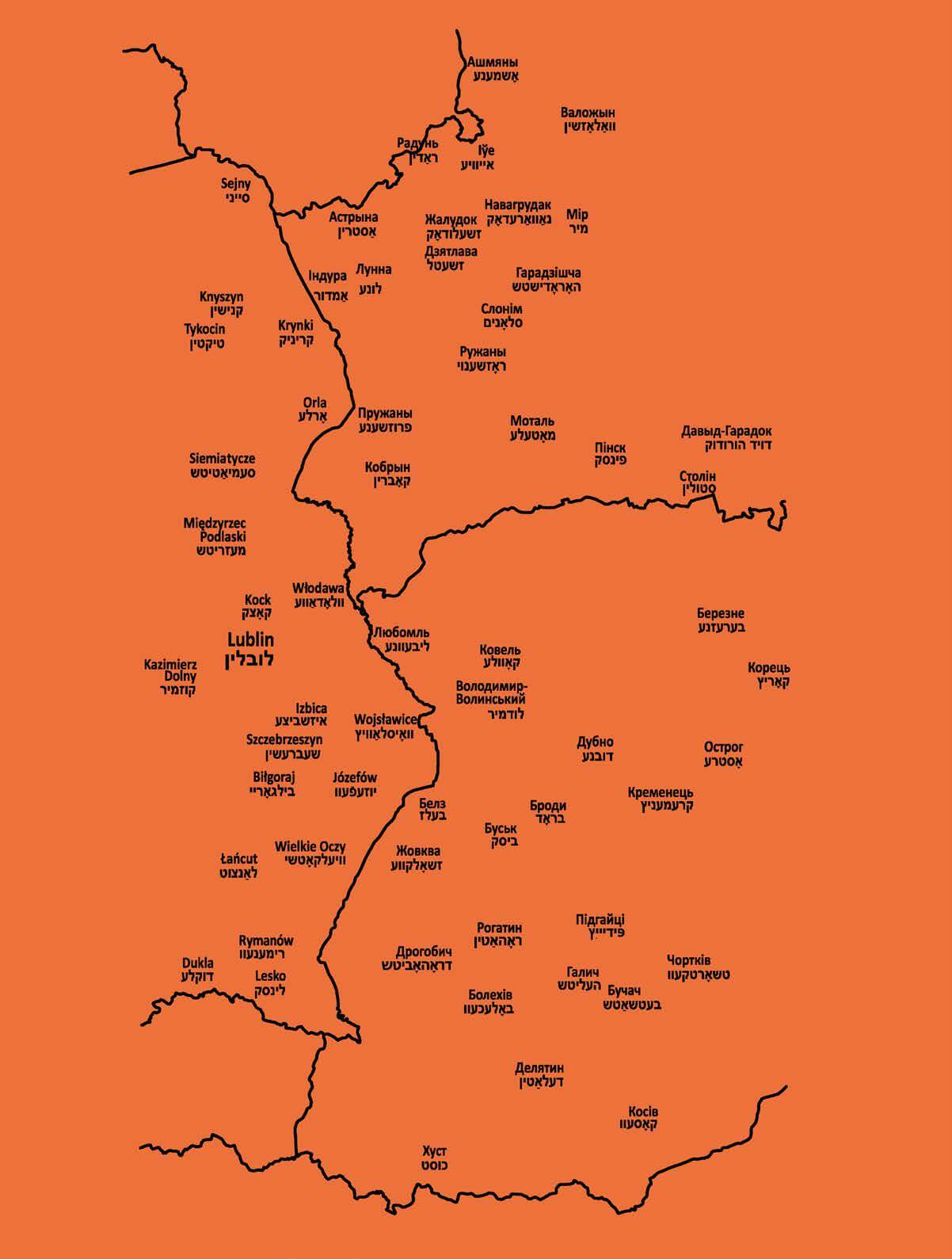

We devoted particular attention to a cultural phenomenon that was unique to central and eastern Europe, and which strongly influenced the local cultural landscape: the shtetl (Yiddish for a small town). There are over fifteen hundred towns in central and eastern Europe that could be called a shtetl. After conducting an initial inventory of Jewish cultural heritage resources and assessing their accessibility, we chose sixty towns (twenty from each country, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine), for which tourism development tools were designed—guidebook, map, website, traveling exhibition, training tours for tour guides. In 2019, Shtetl Routes joined the European Routes of Jewish Heritage, one of the Council of Europe’s certified Cultural Routes.

There are over fifteen hundred towns in central and eastern Europe that could be called a shtetl.

What motivates people to take a journey through former shtetls? One of the most important reasons for tourists, both individuals and groups, is education. Most visitors at the Jewish heritage sites do not have personal ties to Judaism. There are many study groups interested in either Jewish heritage or the history of the Holocaust, usually both. A relatively small, but emotionally involved group of travelers visit places connected with their family’s past. A large group of Jews, usually members of ultra-Orthodox Hasidic communities, travel to Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus to visit graves of tzaddikim. A special group of visitors is youth from Israel who participate in compulsory high school trips to Holocaust sites. Current citizens also visit Jewish heritage sites as part of their local cultural landscape. Finally, some mainstream tourists learn about Jewish culture as part of the culture and traditions of a certain region.

What happens when a tourist’s gaze is focused on a former shtetl? Away from the metropolises, a traveler can see important sites and artifacts of Jewish cultural heritage, such as synagogues, yeshivas, cemeteries, various secular places (e.g., buildings related to schools, libraries, athletic organizations, theatres, and political parties), the houses where prominent people grew up (e.g., the home of the first president of Israel, Chaim Weizman, in Motol, Belarus, or Shai Agnon’s family home in Buchach, Ukraine). Tourist attractions also include synagogue museums (e.g., in Tykocin and Włodawa in Poland), theme museums like the Jewish Resistance Museum in Navahrudak (Belarus), or open-air ethnographic museums within the “shtetl” sector (Sanok and Lublin in Poland). Small collections of Jewish ceremonial art or material culture artifacts are often included in local museum exhibitions. Most of the former synagogues are now used for a wide variety of nonreligious functions, as cultural centers, libraries, or concert halls; commemorative plaques highlight the historical significance of a building. Occasionally, these serve as sites for Jewish commemorative events. Apart from the tangible heritage, this region is filled with rich intangible cultural heritage, too, since the Jewish borderland communities cultivated celebrated authors, thinkers, and artists.

Detail from back cover of Emil Majuk, ed. Shtetl Routes: Travels through the Forgotten Continent. (Lublin: Ośrodek “Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN,” 2018) Courtesy of the Shtetl Routes, www.shtetlroutes.eu

Inevitably, the trail of old shtetls is a journey through places affected by genocide: ruins, devastated cemeteries, mass murder sites. This is also part of the local history, and the traveler can learn how day-to-day coexistence can be destroyed by hatred and prejudice. Presenting the diverse contexts in which Jewish cultural heritage functions can be the basis of valuable tourism-related activities—such as Leora Tec’s “Bridge to Poland” program.

Jewish heritage tourism is a part of the development of new forms of tourism focusing on cultural heritage, but on the other hand, it also stems from local communities’ appreciation of multicultural heritage in the process of building their local

identities. Both kinds of shtetl experiences—the centuries of life living in cultural diversity as well as the destruction caused by hatred for the Other—are highly important for European identity. Although creating a tourist product based

on such a painful and complicated history requires a lot of knowledge, moral sensitivity, attention to context, as well as awareness of the various backgrounds of potential visitors, properly conducted tourism of Jewish heritage holds great

potential

for civic education and counteracting xenophobia. It is especially important on a local level.

Presenting the diverse contexts in which Jewish cultural heritage functions can be the basis of valuable tourism …

As for the answer to “how to tell the story?,” the key element seems to be the creation of a “community of shared heritage,” bringing together local government and activists, Jewish social and religious organizations, descendants of former Jewish residents, as well as experts to create synergies and build positive social capital around the cultural, touristic, and educational aspects of Jewish heritage, as well as around the need to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust.

Internet resources:

Shtetl Routes: www.shtetlroutes.eu

Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre Centre: www.teatrnn.pl/en

European Routes of Jewish Heritage: jewisheritage.org

Bridge to Poland: www.bridgetopoland.com

We carried out the Shtetl Routes project in a seemingly stable and peaceful situation, before the outbreak of the pandemic, before the tightening of repression in Belarus by the Lukashenko regime and, above all, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation.

Unfortunately, writing about cultural tourism in a situation of war is just a theoretical intellectual exercise. The network created by Shtetl Routes is now used to transfer humanitarian aid and medical supplies to our Ukrainian friends. However, I very much hope that the aggressors and tyrants will be defeated and we will be able to return to common travels in the footsteps of the Jewish cultural heritage of the borderlands of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine.

Emil Majuk a political scientist and cultural expert specializing in the interpretation of cultural heritage. He coordinates the projects “Shtetl Routes. Jewish cultural heritage in cross-border tourism of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine” and “Jewish History Tours,” for the “Grodzka Gate - NN Theater” Centre in Lublin (Poland) and is president of the Panorama of Cultures Association, which aims to popularize interesting cultural phenomena from Central and Eastern Europe. He is coauthor, with Monika Tarajko, of Leżajsk. In the Footsteps of Tzaddik Elimelekh and Jewish Cultural Heritage (Leżajsk, 2021) and editor of Shtetl Routes: Travels Through the Forgotten Continent (Lublin, 2018).