Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

Some Jews were in search of diamonds, some Jews were in search of God—they all went to Jerusalem. They came from different parts of the Italian peninsula and faced a long journey by sea and by land, using the best travel agency available at the end of the Middle Ages: the city of Venice and its amazing galleys. Surrounded by Christian pilgrims, they left diaries and wrote letters to their relatives in Italy, explaining their unusual experiences.

Page from Meshullam da Volterra. An Exposition of a Coastal Route in the Mediterranean and Adriatic from Naples to Jerusalem, with the return to Venice. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Plut.44.11, 31v.

Meshullam da Volterra was one of them. A wealthy merchant, a boon companion of Lorenzo the Magnificent —the famous lord who ran the show in Florence and really loved Jewish culture—Meshullam left his native Volterra in 1481 for Jerusalem in order to fulfill an unspecified vow. Charged with sexual violence against a Christian woman and for owning “some blasphemous books” denying the virginity of the Holy Mary some twenty years before, Meshullam never fully explains why he decided to go to Jerusalem. Or maybe he did, but the first part of his diary has been lost, and the manuscript containing his text—still kept in the magnificent Medicea Laurenziana Library designed by Michelangelo in Florence—starts in the middle of a sea battle along the shores of Rhodes, in the eastern Mediterranean sea. Meshullam is on board a Genoese ship, when suddenly two boats approach it, with a threatening display and no flag: Are they Catalan corsairs, known to be totally indifferent to the law of the sea? Oh no, they are Venetians, and well-armed. But they are not able to overcome the brave Genoese, so the Venetians turn to a sneaky compromise when they find out that there are some Jews on board with their unseized prey. “Give them and their goods to us,” they tell the Genoese ship commander, “and we will leave you alone.” The answer of the Genoese patron is clear: “I won’t give you even a twisted shoe of them, as they are under my protection. I gave my word and I won’t sacrifice one of them to save us.” Back home, the Venetian patron, Federigo Giustiniani, will lose his position and pay a fine of 10,000 ducats, an incredible sum of money that the Genoese counterpart will receive as payment for damages.

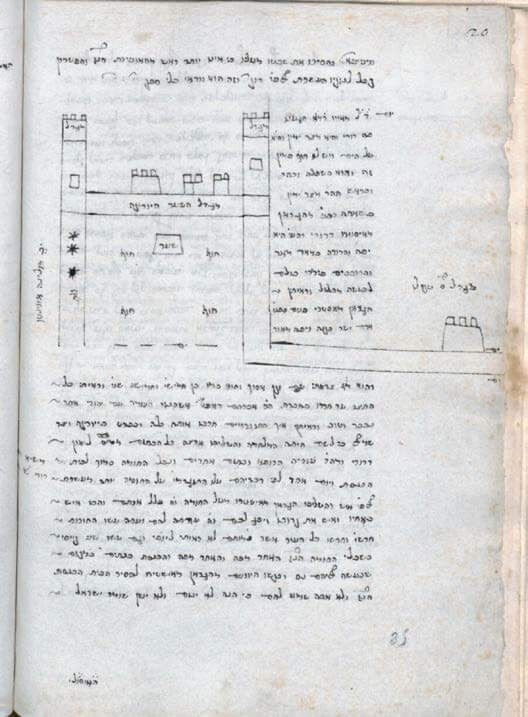

Page with drawing representing the port of Rhodes in Meshullam da Volterra. An Exposition of a Coastal Route in the Mediterranean and Adriatic from Naples to Jerusalem, with the return to Venice. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Plut.44.11, 35r.

Far from indicating a generally positive attitude towards the Jews, this episode rather shows the high esteem Meshullam holds. A few days later, when a sailor of the ship pronounced some offensive words against Meshullam during a forced stop, the sailor was denounced to the patron, who personally looked for the offender, tied him to the mast of the ship, and beat him in plain view of the people on board. Among the onlookers was Ovadiah of Bertinoro, an Italian Jewish rabbi and banker, commonly known as Bartenura for his famous commentary on the Mishnah. He was traveling to Alexandria, in Egypt, aiming to reach Jerusalem and make Aliyah, and when he saw what happened to the poor sailor he thought that it was a disproportionate reaction to a verbal offense; it also marked a negative shift in the attitude the sailors had towards the Jews on board. Meshullam probably thought that this was perfectly in line with the respect he deserved, but also that it might be better to lie low for a while. He took a different ship as soon as it was possible.

Instead of trying to rehabilitate his soul, Meshullam was much more interested in purchasing gems and precious stones.

Meshullam did not at all share the religious views of the Italian Jewish pilgrims to ʾEreẓ Yisraʾel in the same period, who were prompted by rumors about the imminent coming of the messiah to leave home and settle in Jerusalem forever. When they finally reached Jerusalem, they wept with joy, and started to collect data about the ten lost tribes, which were also deemed to be about to return “home” and fight for the redemption of the Jewish people. Not a sign of this messianic

atmosphere appears in Meshullam’s diary. Reading his diary, one has the feeling that Egypt, and thus Cairo, with its incredible markets, or Damascus, with four bazaars and a spa, silk, spices, fruits, and colors all over, were the highlights of his journey, and not Jerusalem. Instead of trying to rehabilitate his soul, Meshullam was much more interested in purchasing gems and precious stones. When he finally arrives in Jerusalem, Meshullam dedicates only a few words to the holy city: “This is the land of milk and honey,” and that’s it. He despises the Oriental tradition of the Jews in the Middle East, considering them too “Islamic” to his taste: when they enter a synagogue, they take off their shoes and sit on the floor. Meshullam considers himself an honorable merchant and fully aligned with the Italian Christian mentality and its sense of respectability. Although written in Hebrew, his diary is so full of Italian terms transliterated in Hebrew letters and uses “honor” so frequently that many scholars believe that Meshullam was primarily writing for a non-Jewish audience. For him, going East does not mean looking for redemption. He feels perfectly integrated at home in Tuscany with his Jewish and Christian friends, and feels the same sense of Otherness Christian pilgrims felt when traveling to the Holy Land.

Meshullam is the last witness of the Golden Age of the Jews in the little town of Volterra. By the end of the fifteenth century, when Meshullam was still alive, the Jews of Volterra were no longer permitted to run lending banks in town, and in a few years, the situation for the Jews got so bad that many of Meshullam’s relatives, including all his children, converted to Christianity. Meshullam was one of the last to travel for pleasure and return.

Samuela Marconcini is an independent researcher in Milan who writes scientific articles with a special focus on the history of the Jews in Italy. Her book, Per amor del cielo. Farsi cristiani a Firenze tra Seicento a Settecento (Firenze University Press, 2016; For Heaven’s Sake. Becoming Christian in Florence between the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries), received the Sangalli Prize for Religious History.