Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

“Tracing the twentieth-century history of a Jewish family inevitably means facing counterfactuals. What if ... would they have ... if only. What losses could have been avoided if a letter had been answered, a visa signed, a ship allowed to make landfall,” writes Hannah Pressman in a piece reflecting on the many paths that led her family to the United States (in Sephardic Trajectories [Istanbul: Koç University Press, 2021]). Pressman’s Ottoman Sephardic great-grandmother, Estrella Leon, was born in Rhodes in 1892, and her great-grandfather, Haim Galante, was an Ottoman Sephardi from Bodrum in southwestern Anatolia. Estrella and Haim got married in South Africa, where they had traveled in the first quarter of the twentieth century, and their descendants live in the United States today. In her work-in-process titled “Galante’s Daughter: A Sephardic Family Journey,” Hannah strives to merge traces of her family’s trajectories through “grassroots sources.” Her sources are located in different geographies with varying political, cultural, and social dynamics. This is a challenging history to narrate, exceptional yet similar to many other trajectories followed by Ottoman Sephardic Jews. The members of Pressman’s family are only two of many thousands of Ottoman Sephardim who left their homeland at the turn of the century to build new lives in distant lands. The trajectories that Ottoman Sephardic Jews followed to reach their final destinations left behind numerous traces in their personal belongings, traces that can help us better understand their experiences, emotions, dreams, hopes, hardships, crises, and disappointments as they traveled and moved around the globe.

These objects had traveled together with their original owners across the world …

As the co-editors of Sephardic Trajectories, we started thinking over the trajectories of Ottoman Sephardim in 2014–2015, when we were both junior research fellows at the Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç University (ANAMED). At the time, as a part of a research assistantship at the University of Washington, Oscar was working together with Devin Naar on the diary of Leon Behar, an Ottoman Sephardi who immigrated to Seattle in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Written in both Ottoman Turkish and Ladino, the diary’s content and story led Oscar to wonder about the stories behind the many objects in the collection, many of which had traveled from Istanbul, Izmir, and Thrace to Seattle. Kerem, on the other hand, was working on his DPhil project examining the intellectual trajectories of three late Ottoman intellectuals who were Ottomanists in the late Ottoman Empire and turned into nationalists in the post-Ottoman period, and whose travels across the empire and beyond were important to their ideas about Ottomanism, education, language, and later, nationalism. One of the intellectuals Kerem worked on was Abraham Galante, a prolific and prominent historian of the Jewish people in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. As a part of his research, Kerem was interested in questions concerning how to study the trajectories of people who lived through times when political boundaries, orders, and identities were shifting. Some of these trajectories included travel, migration, and exile. At the time, we became inspired by the many objects hosted in the Sephardic Studies Collection at the University of Washington and wanted to know more about them and their stories. These objects had traveled together with their original owners across the world, they had moved into the houses of their descendants, and now were moving again, this time into a university collection and a digital archive. As we uncovered the stories behind some of these objects, we reflected on how to engage with the many layers of stories that might be told in relation to multiple trajectories of Ottoman Sephardim through the objects they left behind.

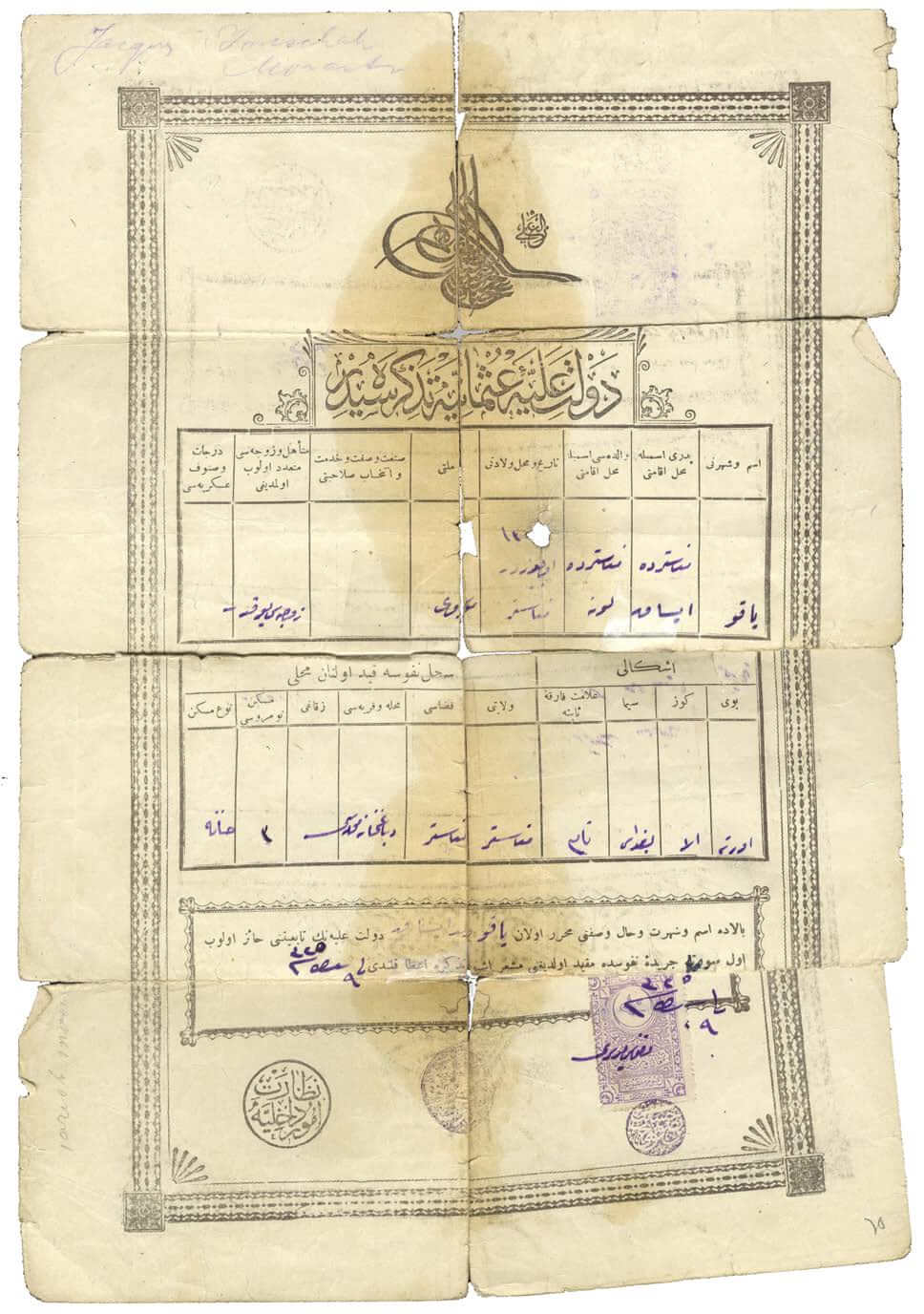

Jacob Youchah's Ottoman Birth Certificate. ST001132, Sephardic Studies Digital Collection, University of Washington. Courtesy of Elayna J. Youchah.

In Sephardic Trajectories we were able to publish some histories and reflections about movement, travel, and immigration, and their entanglements with objects. But the UW Sephardic Studies collection is full of stories yet to be told. To highlight the many possibilities for future research that Sephardic Trajectories hopes to inspire, we want to focus here on one example in the collection that is not included in the book: the Youchah family’s identity documents, donated to the UWSSC. The story of these documents provides us with a good start to examine the traces of the transnational migrations of Ottoman Sephardim. The Youchah family did not have any connection to Seattle. They settled and lived in New York. Despite this, Elayna Youchah, an attorney in Las Vegas, chose to donate the Youchah family documents to the collection in accordance with the wishes of her late father, Michael Youchah, who discovered that the Sephardic Studies Program at the University of Washington was developing a Sephardic archive shortly before he passed away.

Michael’s parents were Ottoman-born Sephardic Jews. His father, Jacob Isaac Youchah, was born in 1885 in Monastir (Ott., Manastır; modern-day Bitola, Macedonia) as an Ottoman citizen. He was the son of Isaac Youchah, a grain merchant. Jacob had eight siblings, four of whom immigrated to the United States. Michael’s mother, Gentile (“Jennie”) née Covo, was born to a prominent family of journalists in Salonica in 1899. On her maternal side, she was a great-granddaughter of Saadi a-Levi Ashkenazi, the founder of the first Ladino newspaper in Salonica, La Epoka (1875–1911). Salonica was a port city with extensive international networks, a center of commerce in the region, a center of banking, and one of the engines of manufacturing in the empire at the turn of the century. More importantly, the Jewish community not only constituted the majority of the population, it was also the dominant actor in the economic life of the city. Jacob and Jennie married in the United States in 1919.

As people moved from Ottoman lands, their ideas, emotions, customs, daily routines, and hopes traveled with them.

Although Jacob and Jennie built their own family in the United States, they never cut their ties with their homes in the former Ottoman domains. Amid shifting political borders and a new global political order following the First World War, Jacob Youchah obtained a passport from the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and an identity card from Greece. Jennie Youchah held a Greek identity card until she lost her citizenship following Jacob’s receipt of US citizenship in 1930.i Both traveled back to visit their homes in former Ottoman lands on several occasions. While Jacob aimed to visit Monastir in 1919 (then part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which later became Yugoslavia) to find his mother, Jennie went back to Salonica (then part of Greece) to visit her sick father before he passed away. The change in their legal identities was a manifestation of sociopolitical transformations in their former homelands that continued to shape their political and legal status. More importantly, the documents left behind by the Youchahs and donated to the UWSCC provide scholars and community members with a chance to trace back the stories, travels, and history of their families, their friends, and their communities from the last days of the Ottoman Empire to the present.

As people moved from Ottoman lands, their ideas, emotions, customs, daily routines, and hopes traveled with them. While today most of the early immigrants are not alive, the objects they left to us continue to tell their story. This history includes the movement of objects and family heirlooms from Ottoman lands to the United States and their more recent transformation from household objects into a collection of historical objects. In other words, these objects, too, have traveled, and their trajectories form a history of Ottoman Sephardic material culture beyond the territorial and periodical delimitations of the Ottoman Empire.

Oscar Aguirre-Mandujano is assistant professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of the early modern Ottoman Empire. He is currently working on his first monograph, on the relationship between literary composition, Sufi doctrine, and political thought in the early modern Islamic world.

Kerem Tınaz is assistant professor of History at Koç University, where he teaches courses on the history of Ottoman Empire and Turkey. His research focuses on the intellectual and cultural history of the late Ottoman Empire with a particular interest in identity, ideology, and networks.

i According to the UWSSC’s catalogue, Jennie Youchah’s affidavit of identity and nationality document were to be used in lieu of a passport. Jennie is listed as a housewife living in 1263 Grant Avenue, Bronx, NY. She was born in Salonica on March 7, 1899. According to the information we have at hand, Jenni wanted to visit her sick father in Salonica, hoping to leave New York on July 3, 1937. But she had lost her nationality when her husband became a US citizen on July 17, 1930. See materials related to the Youchah family in the UWSSC, items 1124–1143. We are thankful to Devin Naar and Ty Alhadeff for sharing with us the preliminary catalogue of the collection while working on this piece.